We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

A CONSPIRACY OF DUNCES…

This website was down all day yesterday due to a dark conspiracy of the people at Bluehost, LISA’s web provider, who decided to all become incompetent at once. Not really. Incompetence has been Bluehost’s theme for years…

TEXTUALISM TAKES IT ON THE CHIN

The Supreme Court on Friday narrowly interpreted 18 USC § 3553(f), the “safety valve” provision that was rewritten as part of the First Step Act, to “den[y] thousands of inmates a chance of seeking a shorter sentence,” according to NBC News.

Many Supreme Court observers believed the Court would approach Friday’s case – Pulsifer v. United States – textually. “Textualism” is the interpretation of the law based exclusively on the ordinary meaning of the legal text. You know, like “and” means “and” and not “or.” But the Court surprised the parties and observers in more ways than one.

Many Supreme Court observers believed the Court would approach Friday’s case – Pulsifer v. United States – textually. “Textualism” is the interpretation of the law based exclusively on the ordinary meaning of the legal text. You know, like “and” means “and” and not “or.” But the Court surprised the parties and observers in more ways than one.

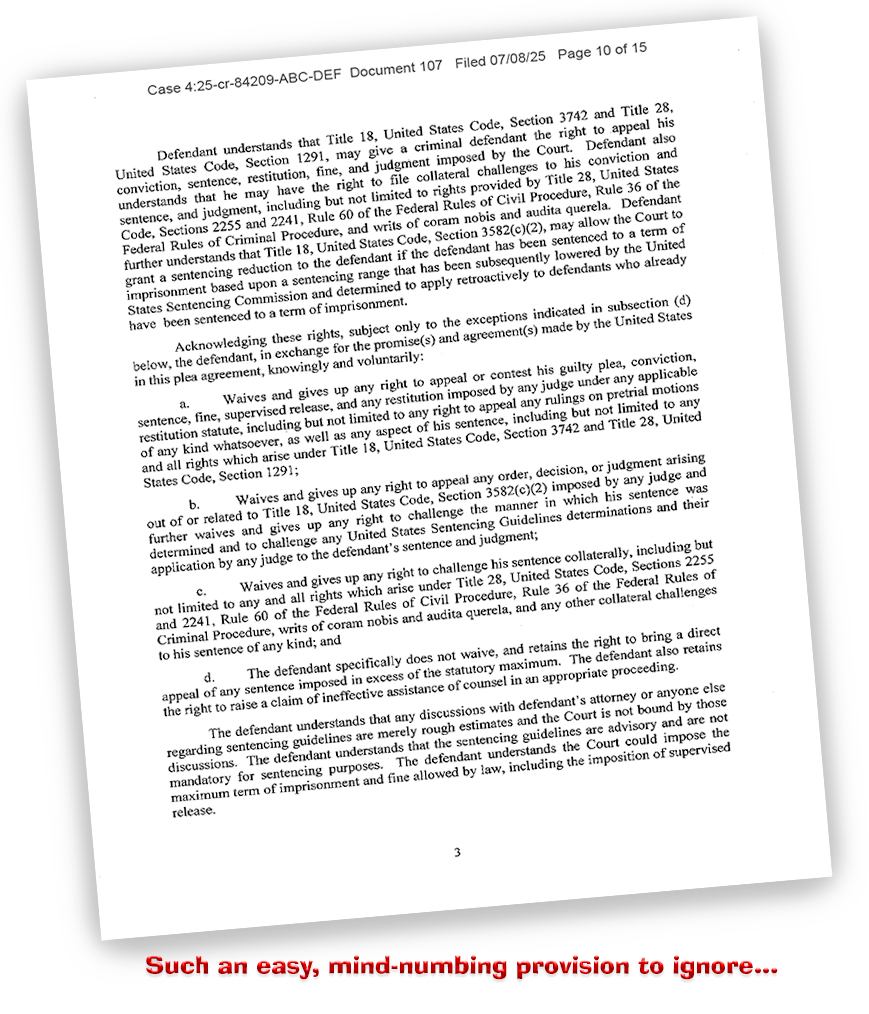

Justice Elana Kagan’s opinion at first blush seems to be something only your high school English teacher could love. The case concerned the “safety valve” provision, which exempts some drug defendants from mandatory minimum sentences if they meet a list of conditions. One of those (3553(f)(1)) says the defendant can’t have “more than 4 criminal history points… a prior 3-point offense… AND a prior 2-point violent offense…” (I emphasized “AND” for reasons that will become apparent).

Mark Pulsifer had a prior 3-point felony, so his sentencing judge said he was ineligible for the safety valve. Mark, however, argued that the way (f)(1) is written, a defendant is ineligible only if he fails all three conditions. That is, Mark said, he was qualified for the safety valve unless he had all three of “more than 4 criminal history points AND a prior 3-point offense AND a prior 2-point violent offense.

The Court’s lengthy ruling was little more than an English grammar lesson. In a decision surprising for scrambling ideological alliances on the Court, liberal Justice Kagan wrote for a 6-3 majority made up of traditionally conservative justices, while conservative Neil Gorsuch was joined by two traditionally liberal justices, Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. The holding essentially holds that in the case of the safety valve, “and” means “or.”

The Court’s lengthy ruling was little more than an English grammar lesson. In a decision surprising for scrambling ideological alliances on the Court, liberal Justice Kagan wrote for a 6-3 majority made up of traditionally conservative justices, while conservative Neil Gorsuch was joined by two traditionally liberal justices, Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. The holding essentially holds that in the case of the safety valve, “and” means “or.”

Kagan’s acceptance of the government’s argument relies squarely on a problem of superfluity.” The opinion focused on the fact that under Pulsifer’s reading of the provision, to be ineligible a defendant would have to have a prior 3-point conviction and a prior 2-point conviction. If that were so, the first requirement – that he or she have more than 4 points – was meaningless because to meet conditions two AND three, the defendant would already have to have 5 points. “In addressing eligibility for sentencing relief, Congress specified three particular features of a defendant’s criminal history — A, B, and C,” Kagan wrote. “It would not have done so if A had no possible effect. It would then have enacted: B and C. But while that is the paragraph Pulsifer’s reading produces, it is not the paragraph Congress wrote… [I]f a defendant has a three-point offense under Subparagraph B and a two-point offense under Subparagraph C he will always have more than four criminal-history points under Subparagraph A.

In other words, if reading the plain text of a statute yields a result that seems at odds with what Congress must have intended, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of what Congress must have intended prevails.

To prove her grammatical point, Kagan cites both The Very Hungry Caterpillar and Article III of the Constitution. She notes that Article III extends the “judicial Power… to all Cases… arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties.” This, she says, plainly applies to cases arising under any one of the three listed bodies of law but does not require that the cases arise under ALL three.

In his dissent, Gorsuch complained that the decision significantly limits the goals of the First Step Act. “Adopting the government’s preferred interpretation guarantees that thousands more people in the federal criminal justice system will be denied a chance—just a chance—at an individualized sentence. For them, the First Step Act offers no hope. Nor, it seems, is there any rule of statutory interpretation the government won’t set aside to reach that result,” Gorsuch wrote. “Ordinary meaning is its first victim. Contextual clues follow. Our traditional practice of construing penal laws strictly falls by the wayside too. Replacing all that are policy concerns we have no business considering.”

In his dissent, Gorsuch complained that the decision significantly limits the goals of the First Step Act. “Adopting the government’s preferred interpretation guarantees that thousands more people in the federal criminal justice system will be denied a chance—just a chance—at an individualized sentence. For them, the First Step Act offers no hope. Nor, it seems, is there any rule of statutory interpretation the government won’t set aside to reach that result,” Gorsuch wrote. “Ordinary meaning is its first victim. Contextual clues follow. Our traditional practice of construing penal laws strictly falls by the wayside too. Replacing all that are policy concerns we have no business considering.”

Besides dramatically limiting those eligible for a safety valve non-mandatory drug sentence, Friday’s decision dashes the hope of some seeking a zero-point retroactive Guidelines 4C.1 2-level reduction. One of the conditions to qualify for that reduction is that a “defendant did not receive an adjustment under 3B1.1 (Aggravating Role) and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in 21 USC 848.” Some read this as being that a defendant has to have both a 3B1.1 aggravating role AND a 21 USC 848 conviction. Other courts have read this as disqualifying all defendants having either a 3B1.1 enhancement OR an 848 conviction.

The decision stamps “denied” on the 5 pct of defendants annually getting a USSC § 3B1.1 leader/organizer/manager/supervisor enhancement.

Writing in his Sentencing Policy and Law blog, Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman observed that the Pulsifer “serves as still more evidence that SCOTUS is no longer one of the most pro-defendant sentencing appeals courts. I got in the habit of making this point for a number of years following the Apprendi/Blakely/Booker line of rulings during a time when most federal circuit courts were often consistently more pro-government on sentencing issues than SCOTUS… But we are clearly in a different time with different Justices having different perspectives on these kinds of sentencing matters.”

Pulsifer v US, Case No 22-340, 2024 U.S. LEXIS 1215 (March 15, 2024)

Reuters, US Supreme Court says thousands of drug offenders can’t seek shorter sentences (March 15, 2024)

Sentencing Law and Policy, In notable 6-3 split, SCOTUS rules in Pulsifer that “and” means “or” for application of First Step safety valve (March 15, 2024)

SCOTUSBlog.com, Supreme Court limits “safety valve” in federal sentencing law (March 15, 2024)

NBC, Supreme Court denies ‘thousands’ of inmates a chance at shorter sentences (March 15, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root