We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SUPREME COURT ERLINGER ARGUMENT MAY LIMIT JUDICIAL FACT-FINDING IN ARMED CAREER CRIMINAL ACT CASES

The Supreme Court justices appears to be siding with the defendant and the government on the issue of whether a jury instead of a judge has to find that a defendant is eligible for the Armed Career Criminal Act (18 USC 924(e)) mandatory 15-life sentence.

The Supreme Court justices appears to be siding with the defendant and the government on the issue of whether a jury instead of a judge has to find that a defendant is eligible for the Armed Career Criminal Act (18 USC 924(e)) mandatory 15-life sentence.

Under 18 USC 922(g)(1), a person previously convicted of a felony may not possess a gun or ammo. Violators face a sentence of 0 to 15 years. But if the defendant has three prior drug or violent crime convictions, the ACCA raises the minimum sentence to 15 years.

There are catches, including the requirement that the prior offenses have been committed on different occasions. Two years ago, in Wooden v. United States, the justices adopted a standard for determining when crimes are committed during a single occasion. In Wednesday’s argument, the issue was whether the 6th Amendment right to a jury trial in criminal cases means the jury rather than a judge must find the facts that qualify a defendant for an ACCA sentence.

That question is important because the Supreme Court has previously said that any fact that increases a penalty, other than the fact of a prior conviction, must be decided by the trier of fact, typically a jury, and proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Back in 2000, the Court held in Apprendi v. New Jersey that any facts that increased the statutory sentence must be decided by a jury. But there is an exception: in Almendarez-Torres v. United States, the Court held that the fact of a prior conviction may be found by a judge.

Justice Clarence Thomas has waged a lonely battle against Almendarez-Torres since Apprendi, and unsurprisingly asked as his first question after the defense’s opening statement – which urged limits on the Almendarez-Torres prior-conviction exception to Apprendi – “Wouldn’t it be more straightforward to overrule Almendarez-Torres?”

Some background: A judge sentenced Paul Erlinger to the ACCA 15-year minimum sentence based on the convictions for four burglaries committed when the defendant was 18 years old. Paul claimed the four burglaries were not committed on different occasions and thus could be used to sentence him under the law.

Paul argued the judge violated the 6th Amendment by engaging in judicial fact-finding but lost at the trial court and 7th Circuit.

Wednesday’s argument focused both on history and practicality.

The Supreme Court has moved broadly toward testing constitutional questions against historical analogues and traditions when reviewing present-day laws or practices. In the Court’s June 2022 New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn v. Bruen holding, the majority established a new test instructing courts to consider whether a similar law to the challenged one – such as banning felons from possessing guns – was on the books when the 2nd Amendment was enacted in 1791 or when the 14th Amendment was enacted in 1868.

Since then, arguments over the history and tradition behind different constitutional rights have been mainstays in briefs filed with the court.

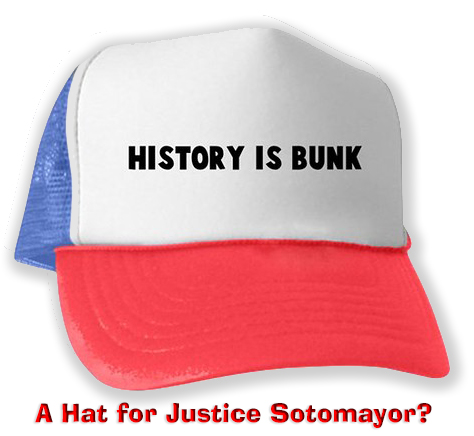

“When we start talking about history, I get very annoyed, because in every history, there are exceptions,” Justice Sotomayor said during Wednesday’s session. “The question then becomes how many exceptions defeat the general rule.”

“When we start talking about history, I get very annoyed, because in every history, there are exceptions,” Justice Sotomayor said during Wednesday’s session. “The question then becomes how many exceptions defeat the general rule.”

In Paul Erlinger’s case, she argued, it did not matter whether four or eight states allowed judges to make enhanced sentencing decisions around the year 1791 because either number did not “defeat the general rule” that defendants are entitled to jury trials.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, on the other hand, found history relevant. “The text itself of the Constitution does not tell us the answer, just the bare words, correct?” he asked the court-appointed amicus arguing in favor of the ACCA. “So then we usually look to history. We might not like it, but unless we’re just making it up, I don’t know where else we’re going to look.”

The other issue, how a rule requiring juries to make habitual defender determinations would work in practice, was more problematic.

Justice Samuel Alito said the inquiry would be difficult for a jury because it centers on a “multidimensional and nuanced” look at a defendant’s past convictions. But the Dept of Justice attorney, while agreeing that that letting a jury decide would add some burden for prosecutors, “We believe it will be manageable.”

Erlinger’s lawyer noted that most criminal cases result in plea deals, meaning that this will be an issue in only a “handful of cases a year.”

Court-appointed counsel defending the ACCA warned that putting recidivism issues in front of a jury would alert it to the defendant’s past, and “would gravely prejudice defendants.” But Justice Sotomayor said that the criminal defense bar has already sided with Erlinger, suggesting that defense attorneys don’t think it will harm defendants to put the prior convictions in front of the jury.

Chief Justice Roberts suggested the answer to any problem of jury prejudice would be to present the issue about prior crimes only after a jury has convicted a defendant of the current one in a bifurcated trial.

Wednesday’s argument suggested that the question of who must decide the issue of the existence of a prior conviction – the Almendarez-Torres issue – will not be disturbed by the Erlinger decision. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said that the “carve out” holds that judges can decide “the fact of a prior conviction. But Erlinger and the government say the rule should be read more narrowly to allow a judge to consider only facts “inherent” to the past convictions rather than conduct related to the offenses, like whether they were part of the same “occurrence.”

“Just move the fact-finding from the judge over to the jury, I don’t think it’s very much to ask,” Erlinger’s lawyer argued.

Justice Jackson wondered if upholding Erlinger’s position meant repeated litigation of crimes for which the defendant has already been convicted. Erlinger’s lawyer replied that that’s already happening: “It’s just whether or not the judge or the jury is going to make the finding.”

Erlinger v. United States, Case No. 23-370 (oral argument March 27, 2024)

Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000)

Almendarez-Torres v. United States, 523 U.S. 224 (1998)

Bloomberg Law, High Court Suggests Robust Jury Right for Longer Sentences (March 27, 2024)

Courthouse News Service, Supreme Court leans toward jury review for career criminal sentences (March 27, 2024)

Law360.com, Sotomayor ‘Annoyed’ By Supreme Court’s Focus On History (March 27, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root