We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

‘SHUT UP AND SIGN’ LEADS TO A LOT OF BUYER REMORSE

About 95% of all federal indictments end with a plea agreement where the defendant agrees to take a guilty plea in exchange for government promises that often seem evanescent if not illusory. If I had a dime for every prisoner who has told me that he or she only signed because defense counsel said to, I would be writing this on the beach of my private Caribbean island instead of at a desk looking out at February snow in Ohio.

Two cases decided last week remind all prisoners – including those who have already signed their plea agreements – that in a plea agreement, every promise counts. A defense attorney’s disservice to the client is never greater than when he or she rushes them into signing a “good deal” without first painstakingly walking the defendant through every provision and explaining it in detail.

Two cases decided last week remind all prisoners – including those who have already signed their plea agreements – that in a plea agreement, every promise counts. A defense attorney’s disservice to the client is never greater than when he or she rushes them into signing a “good deal” without first painstakingly walking the defendant through every provision and explaining it in detail.

Eric Rudolph (remember him?) decided to express his political views by blowing up Olympic venues and abortion clinics. The innocents he slaughtered in the process were just icing on his demented cake. After five years on the lam, Eric was caught dining out of a dumpster in Murphy, North Carolina, and was later convicted of one 18 USC § 844(i) arson offense and five companion 18 USC § 924(c) counts for using a firearm (bombs studded with nails qualify under the statute as “firearms”) in the commission of the arson.

Eric’s approach to the plea agreement was unrepentant. He said he had “deprived the government of its goal of sentencing me to death,” and that “the fact that I have entered an agreement with the government is purely a tactical choice on my part and in no way legitimates the moral authority of the government to judge this matter or impute my guilt.”

Uh-huh. Eric’s statement brings to mind old Gus McRae (Lonesome Dove) addressing outlaw Dan Suggs, who was about to be executed with his brother but expressed only hatred and contempt:

Gus McCrae: I’ll say this, Suggs; you’re the kind of man it’s a pleasure to hang. If all you can talk is guff, you can talk it to the Devil.

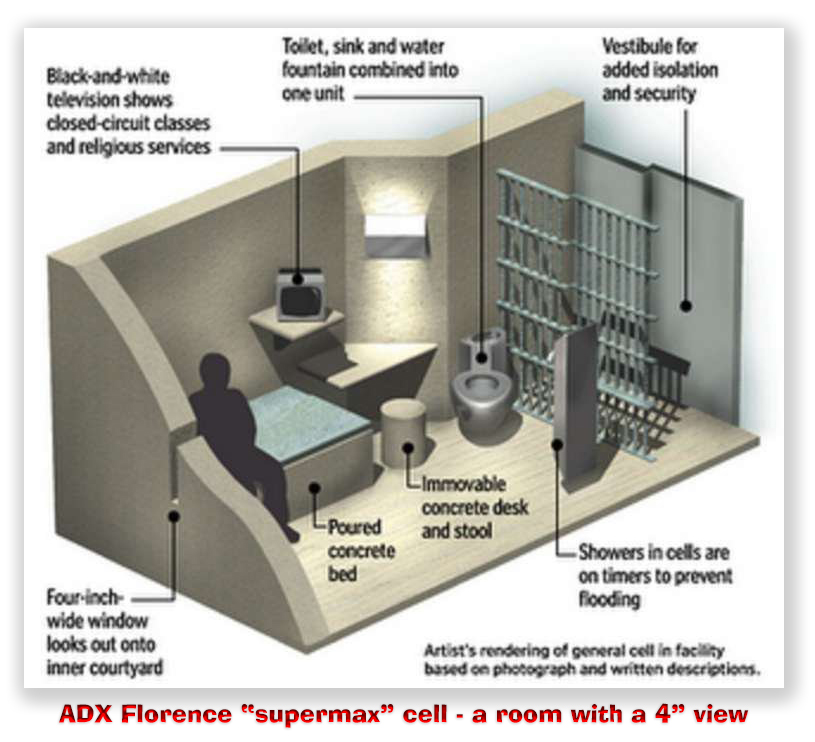

I’m no fan of mandatory life sentences and even less of the death penalty, but it’s amazing how malleable our principles can be when we’re punched in the face with pure-D evil. Eric undeservedly got a life sentence, which he’s spending in the mountains of Colorado (although he never gets to see them from his concrete cell at ADX Florence).

I’m no fan of mandatory life sentences and even less of the death penalty, but it’s amazing how malleable our principles can be when we’re punched in the face with pure-D evil. Eric undeservedly got a life sentence, which he’s spending in the mountains of Colorado (although he never gets to see them from his concrete cell at ADX Florence).

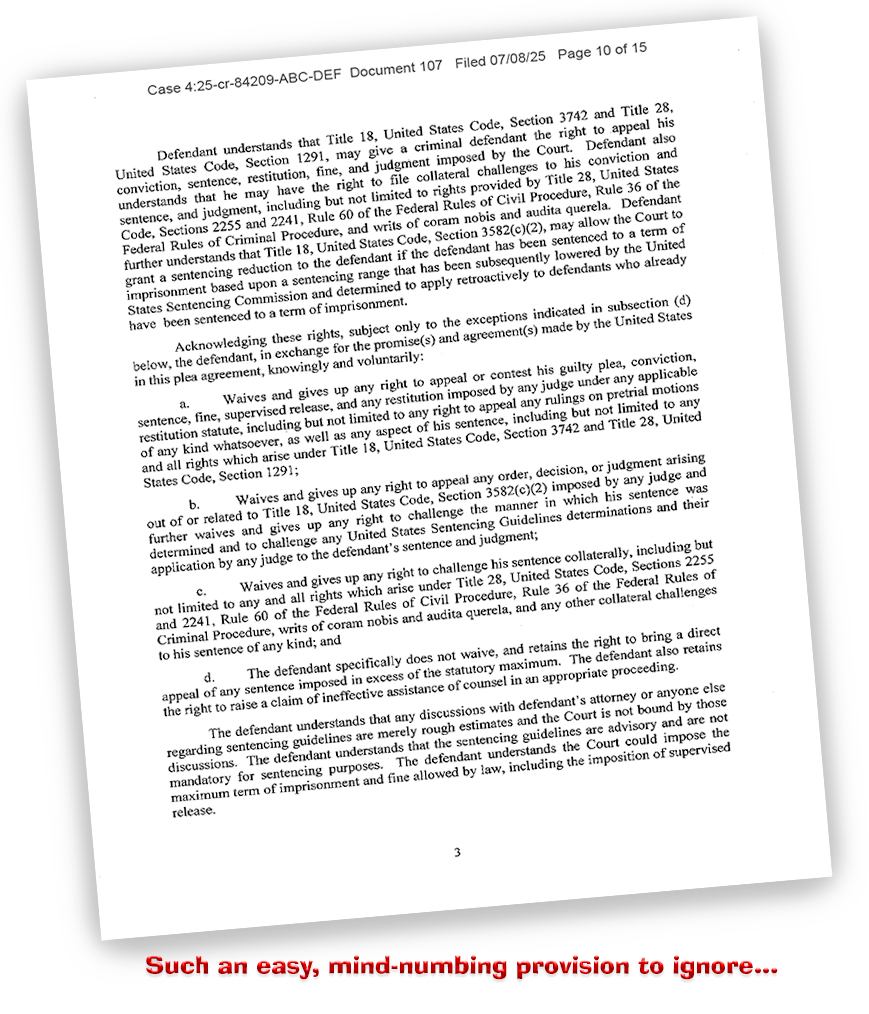

As part of the plea deal he was proud of for depriving the Feds of the death penalty, Eric waived the right to collaterally attack his sentence in any post-conviction proceeding, including under 28 USC § 2255. But because of what the Court disapprovingly calls “the evergreen litigation opportunities introduced by the categorical approach” to § 924(c) litigation,” Eric – who has apparently decided that freedom some day isn’t such a bad goal – has filed two § 2255s so far. Last week, the 11th Circuit turned down his second one as barred by the plea agreement and, in so many words, told Eric to enjoy his place in the mountains for the rest of his life.

In the last few years, courts have applied the Supreme Court’s “categorical” approach to determining whether an offense is a “crime of violence” within the meaning of 18 USC § 924(c)(3)(A), that is, “an offense that is a felony and has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another.” Even Eric’s district court agreed that after the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Davis, his arson offenses were no longer crimes of violence under the federal statute (because one can be convicted of arson for burning down his or her own property). But that didn’t matter, the district court said, because Eric had given away his right to bring a § 2255 motion to correct the error.

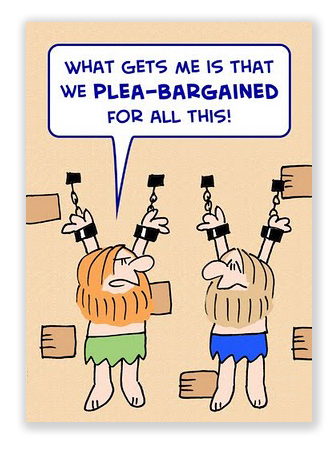

Last week, the 11th Circuit agreed. It held that “a plea agreement is, in essence, a contract between the Government and a criminal defendant. And because it functions as a contract, a plea agreement should be interpreted in accord with what the parties intended. In discerning that intent, the court should avoid construing a plea agreement in a way that would deprive the government of the benefit that it has bargained for and obtained in the plea agreement.”

Eric’s plea deal, the 11th said, contained the common waiver of the right to bring a collateral attack on his sentence. But Eric argued that the plea deal only prohibited collateral attacks on the sentence, while his collateral attack was on the § 924(c) convictions.

Eric’s argument was a dumpster fire, the Circuit said. “The text of 28 USC § 2255, the history of that same statute, and the habeas corpus right that it codified, all point in the same direction: 2255 is a vehicle for attacking sentences, not convictions.” Starting with the origins of English habeas corpus through the codification of 2255 up to last summer’s Supreme Court Jones v. Hendrix decision (where SCOTUS said “Congress created 2255 as a separate remedial vehicle specifically designed for federal prisoners’ collateral attacks on their sentences”), the 11th concluded that the history, the plain text of the statute “shows the same, as does Rudolph’s requested relief… [His] motions are collateral attacks on his sentences, so his plea agreements do not allow them.”

Eric’s argument was a dumpster fire, the Circuit said. “The text of 28 USC § 2255, the history of that same statute, and the habeas corpus right that it codified, all point in the same direction: 2255 is a vehicle for attacking sentences, not convictions.” Starting with the origins of English habeas corpus through the codification of 2255 up to last summer’s Supreme Court Jones v. Hendrix decision (where SCOTUS said “Congress created 2255 as a separate remedial vehicle specifically designed for federal prisoners’ collateral attacks on their sentences”), the 11th concluded that the history, the plain text of the statute “shows the same, as does Rudolph’s requested relief… [His] motions are collateral attacks on his sentences, so his plea agreements do not allow them.”

Winning his § 2255 would have been a huge deal for Eric. The 18 USC § 844(i) conviction carries a maximum 10-year sentence. Each of the § 924(c) convictions carries a maximum of life. Had Eric been allowed to bring the § 2255, he would have gone from his concrete cell straight to walking the streets (something most of his victims would never enjoy again).

* * *

Meanwhile, over in Louisiana, Keesha Dinkins – a front-office worker at Positive Change healthcare clinic – was swept up in a Medicaid billing fraud. She didn’t make a dime from the fraud beyond her normal salary, but her lawyer had her sign a plea agreement for 24 months and restitution of $3.5 million.

Despite the deal she made, she argued that she should not be on the hook to share the restitution equally with Positive Change’s owner (who got a lot more time than she did). Last week, the 5th Circuit told her that it was Positive that it would not Change her restitution:

Despite the deal she made, she argued that she should not be on the hook to share the restitution equally with Positive Change’s owner (who got a lot more time than she did). Last week, the 5th Circuit told her that it was Positive that it would not Change her restitution:

The criminal justice system in this country relies on plea agreements to provide efficient resolutions to criminal cases. Indeed, over 95 percent of federal criminal cases are resolved without trial. It would undermine the principle that plea bargains are contracts to hold that a party can agree to a specific amount of restitution, supported by record evidence, and then in the next breath, challenge an order imposing that exact amount of restitution.

The 5th observed that her plea agreement provided that “Dinkins — not Positive Change — was responsible for the $3.5 million loss.” That is how the judgment will remain.

Rudolph v. United States, Case No 21-12828, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 3278 (11th Cir., February 12, 2024)

United States v. Johnson, Case No 22-30242, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 3487 (5th Cir., February 14, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root