We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

5TH CIRCUIT DERAILS DOJ EFFORT TO DELEGITIMIZE GUIDELINES

I suppose it is unsurprising that the Dept of Justice sees appropriate judicial discretion as a ratchet. It’s fine if a judge employs his or her flexibility to tighten the screws on a defendant, but any attempt to fashion a remedy that seeks to ameliorate harsh sentences that could not be imposed today is seen by the denizens of the US Attorney’s offices as a threat to the republic.

I suppose it is unsurprising that the Dept of Justice sees appropriate judicial discretion as a ratchet. It’s fine if a judge employs his or her flexibility to tighten the screws on a defendant, but any attempt to fashion a remedy that seeks to ameliorate harsh sentences that could not be imposed today is seen by the denizens of the US Attorney’s offices as a threat to the republic.

After the First Step Act permitted prisoners to bring so-called compassionate release motions – petitioning courts under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) to reduce sentences for extraordinary and compelling reasons – courts labored for almost five years to pound square-peg Sentencing Guideline 1B1.13 into the new round hole of defendant-initiated compassionate release motions. The old version of 1B1.13, written back in the day when only the Federal Bureau of Prisons could initiate a compassionate release request, was minimally relevant to the new regime. However, the Sentencing Commission lost its quorum a mere 11 days after First Step was signed into law, and could not promulgate a new § 1B1.13 for prisoner-brought motions.

Nearly all courts of appeal rejected DOJ demands that the old § 1B1.13 be slavishly applied to compassionate release motions, holding that commentary for motions brought by the BOP was inapplicable to motions brought by defendants and that what constituted extraordinary and compelling reasons for compassionate release motions was left to the broad discretion of district courts, limited only by the statute’s directive that rehabilitation alone was an insufficient basis for a sentence reduction.

In the absence of a guiding Sentencing Commission policy statement, appellate courts split on whether district courts could consider non-retroactive changes in the law in deciding whether extraordinary and compelling reasons existed for compassionate release. Such was a major concern. First Step changed mandatory minimum sentences for a number of drug offenses and clarified a drafting blunder in 18 USC § 924(c) – which imposes mandatory consecutive sentences for using or carrying a gun in a drug offense or crime of violence – but did not make those changes retroactive.

In some circuits, prisoners with draconian 50-year-plus sentences for 924(c) offenses that today would carry 15 years could get relief. In other places, appellate courts ruled that such reductions were impermissible because old § 1B1.13 did not permit it.

That was the state of things until last November, when the reconstituted Sentencing Commission’s rewritten 1B1.13 became effective. The new 1B1.13 provided ample guidance as to what a district court must consider to be “extraordinary and compelling” reasons for grant of a 3582(c)(1)(A) motion, including

That was the state of things until last November, when the reconstituted Sentencing Commission’s rewritten 1B1.13 became effective. The new 1B1.13 provided ample guidance as to what a district court must consider to be “extraordinary and compelling” reasons for grant of a 3582(c)(1)(A) motion, including

[i]f a defendant received an unusually long sentence and has served at least 10 years of the term of imprisonment, a change in the law (other than an amendment to the Guidelines Manual that has not been made retroactive) may be considered in determining whether the defendant presents an extraordinary and compelling reason, but only where such change would produce a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence likely to be imposed at the time the motion is filed, and after full consideration of the defendant’s individualized circumstances.

The USSC also added a “catch-all,” authorizing district courts to consider as extraordinary and compelling reasons “any other circumstance or combination of circumstances that, when considered by themselves or together with any of the reasons [listed in 1B1.13] are similar in gravity…”

The DOJ immediately mounted a nationwide attack on the new 1B1.13, arguing (among other things) that allowing the consideration of changes in the law that made the old sentences disparately long exceeded the Commission’s legal authority and supplanted Congress’s legislative role by permitting the revision of sentences that Congress did not wish to make retroactive.

This full-throated attack on the new 1B1.13, which Congress had six months to reject but chose not to, finally got to an appellate court.

Joel Jean was locked up in 2009 for a cocaine distribution crime and a § 924(c) offense. He had three prior state drug convictions, and as a result, he was classified as a Guidelines “career offender,” which came with a recommended sentencing range of 352-425 months. The district court gave him a break, sentencing him to 292 months’ imprisonment.

Joel Jean was locked up in 2009 for a cocaine distribution crime and a § 924(c) offense. He had three prior state drug convictions, and as a result, he was classified as a Guidelines “career offender,” which came with a recommended sentencing range of 352-425 months. The district court gave him a break, sentencing him to 292 months’ imprisonment.

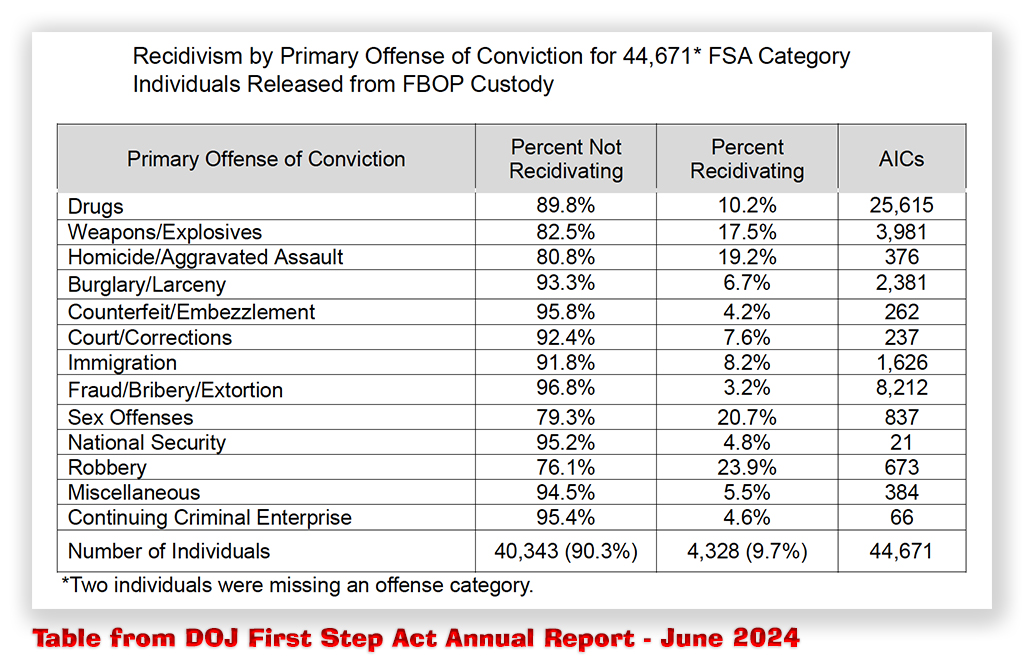

In the years following Joel’s conviction, a series of Supreme Court and 5th Circuit cases redefined what could be considered a qualifying offense for the “career offender” enhancement. Those held that some of Joel’s Texas convictions no longer qualified to make him a “career offender.” As a result, “it is undisputed that if he were to be sentenced today, Joel would not be classified as a career offender under § 4B1.1.”

Joel filed a compassionate release motion, arguing that non-retroactive changes in the law would result in a substantially shorter sentence today if he were sentenced today and that his post-sentencing conduct and rehabilitation weighed in favor of compassionate release.

To be sure, Joel’s rehabilitation efforts – good conduct, successful programming, and comportment that resulted in laudatory letters from BOP staff – were exceptional. The district court was impressed, granting Joel’s motion and resentencing him to time served. The government, however, was dissatisfied with the decade-length pound of flesh it had gotten from Joel. It appealed, arguing that the district court could not consider non-retroactive changes in the law and that Joel should return to prison.

Last week, the 5th Circuit rejected the government’s position, holding that a sentencing court has the “discretion to hold that non-retroactive changes in the law, when combined with extraordinary rehabilitation, amount to extraordinary and compelling reasons warranting compassionate release.”

The Circuit ruled that “there is no textual basis [in statute] for creating a categorical bar against district courts considering non-retroactive changes in the law as one factor” nor did appellate precedent or 1B1.13 prohibit including such factors in a compassionate release calculus.

In Concepcion v. United States, the 5th observed, the Supreme Court held that

Federal courts historically have exercised this broad discretion to consider all relevant information at an initial sentencing hearing, consistent with their responsibility to sentence the whole person before them. That discretion also carries forward to later proceedings that may modify an original sentence. Such discretion is bounded only when Congress or the Constitution expressly limits the type of information a district court may consider in modifying a sentence… [T]he Concepcion Court concluded that nothing limits a district court’s discretion except when expressly set forth by Congress in a statute or by the Constitution. And in the case of the FSA, though the Court noted that “Congress is not shy about placing such limits where it deems them appropriate,” Congress had not expressly limited district courts to considering only certain factors there.

The Circuit noted that Congress “has never wholly excluded the consideration of any factors. Instead, it appropriately affords district courts the discretion to consider a combination of ‘any’ factors particular to the case at hand, limited only by the proscription that “rehabilitation alone was insufficient… [but] did not prohibit district courts from considering rehabilitation in conjunction with other factors.”

Congress adopted § 3582(c)(1)(A) due to the “need for a ‘safety valve’ with respect to situations in which a defendant’s circumstances had changed such that the length of continued incarceration no longer remained equitable,” the Court ruled: “It is within a district court’s sound discretion to hold that non-retroactive changes in the law, in conjunction with other factors such as extraordinary rehabilitation, sufficiently support a motion for compassionate release. To be clear, it is also within a district court’s sound discretion to hold, after fulsome review, that the same do not warrant compassionate release. For this court to hold otherwise would be to limit the discretion of the district courts, contrary to Supreme Court precedent and Congressional intent. We decline the United States’ invitation to impose such a limitation.”

United States v. Jean, Case No. 23-40463, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 17274 (5th Cir. July 15, 2024)

Concepcion v United States, 597 US 481 (2022)

– Thomas L. Root

You may recall that in May, a 9th Circuit three-judge panel held that the 18 USC § 922(g)(1) ban on felons possessing guns was held to violate the Second Amendment rights of a guy convicted of drug trafficking.

You may recall that in May, a 9th Circuit three-judge panel held that the 18 USC § 922(g)(1) ban on felons possessing guns was held to violate the Second Amendment rights of a guy convicted of drug trafficking.

The BOP probably doesn’t like that big white bear, the fact that it is required to deliver on RRC placement despite the agency’s utter failure over five years to ensure that there was enough RRC space. But as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy (or both) figured out, just because you can force yourself to not think about it doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

The BOP probably doesn’t like that big white bear, the fact that it is required to deliver on RRC placement despite the agency’s utter failure over five years to ensure that there was enough RRC space. But as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy (or both) figured out, just because you can force yourself to not think about it doesn’t mean it isn’t there.