We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE HOPEFUL FUTURE OF COMPASSIONATE RELEASE

From the 11th Circuit last week – traditionally, the place where motions for compassionate release went to die – comes a detailed, thoughtful order granting release to a prisoner serving a life sentence for drug distribution.

Bill Vanholten was about 12 years into a life sentence for trafficking cocaine, a sentence he got because he had two prior convictions for selling two dime bags of marijuana, about $20.00 worth, to two undercover cops when he was 19 years old in 1994. In January 2012, Bill was charged with possessing 10 kilograms of cocaine. At the time, a defendant charged with that quantity of cocaine who had two prior drug felonies would get a mandatory life sentence if the government filed what is known as a 21 USC § 851 enhancement with the court.

Bill Vanholten was about 12 years into a life sentence for trafficking cocaine, a sentence he got because he had two prior convictions for selling two dime bags of marijuana, about $20.00 worth, to two undercover cops when he was 19 years old in 1994. In January 2012, Bill was charged with possessing 10 kilograms of cocaine. At the time, a defendant charged with that quantity of cocaine who had two prior drug felonies would get a mandatory life sentence if the government filed what is known as a 21 USC § 851 enhancement with the court.

The government has traditionally used 851 enhancements as a bludgeon to force defendants to cooperate. If the defendant won’t snitch, the government files the 851 and rachets up the minimum sentence dramatically. Bill wouldn’t budge, refusing to identify his source for the coke, so the government filed the 851 notice of two prior drug felonies, a 2006 federal coke charge and one of the “dime bag” offenses. Those two priors mandated a life-without-parole sentence, which, the court said unhappily, it was required to impose.

Six years later, the First Step Act modified the list of prior offenses qualifying for 851 enhancements and lowered the mandatory minimums. After First Step, the “dime bag” offense would not count as a serious drug offense for a 21 USC § 851 enhancement. On top of that, the mandatory minimum sentence for a single 851 enhancement prior dropped to 15 years. If Bill had been sentenced after First Step passed, his court would have only been required to sentence him to 15 years.

The First Step Act also permitted defendants to file sentence reduction motions – so-called compassionate release requests – under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A). Before the Act, only the Federal Bureau of Prisons could bring such a request on an inmate’s behalf, an event as rare as a snow flurry on July 4th. All that stood in the way was the Sentencing Commission’s guideline on compassionate release, USSG § 1B1.13. That guideline, written prior to First Step, narrowly circumscribed what “extraordinary and compelling” reason could justify sentencing reduction and required that any reduction be “consistent” with applicable Sentencing Commission policy.

The First Step Act also permitted defendants to file sentence reduction motions – so-called compassionate release requests – under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A). Before the Act, only the Federal Bureau of Prisons could bring such a request on an inmate’s behalf, an event as rare as a snow flurry on July 4th. All that stood in the way was the Sentencing Commission’s guideline on compassionate release, USSG § 1B1.13. That guideline, written prior to First Step, narrowly circumscribed what “extraordinary and compelling” reason could justify sentencing reduction and required that any reduction be “consistent” with applicable Sentencing Commission policy.

Section 1B1.13 could have been updated by the Sentencing Commission in 2019, but the Commission lost its quorum through the expiration of commissioner terms only a few days after the First Step Act passed.

Most federal circuits recognized the obvious, that the creaking 1B1.13 relic – written long before First Step was even dreamed of – was Commission policy but not “applicable” Commission policy. Only two of the 12 federal circuits remained mired in the past, not permitting any reason for compassionate release not specifically written into the guideline. Bill’s Circuit was one of them.

Four years later, the Sentencing Commission regained a quorum and immediately set to amending 1B1.13. The amendment became effective on November 1, 2023.

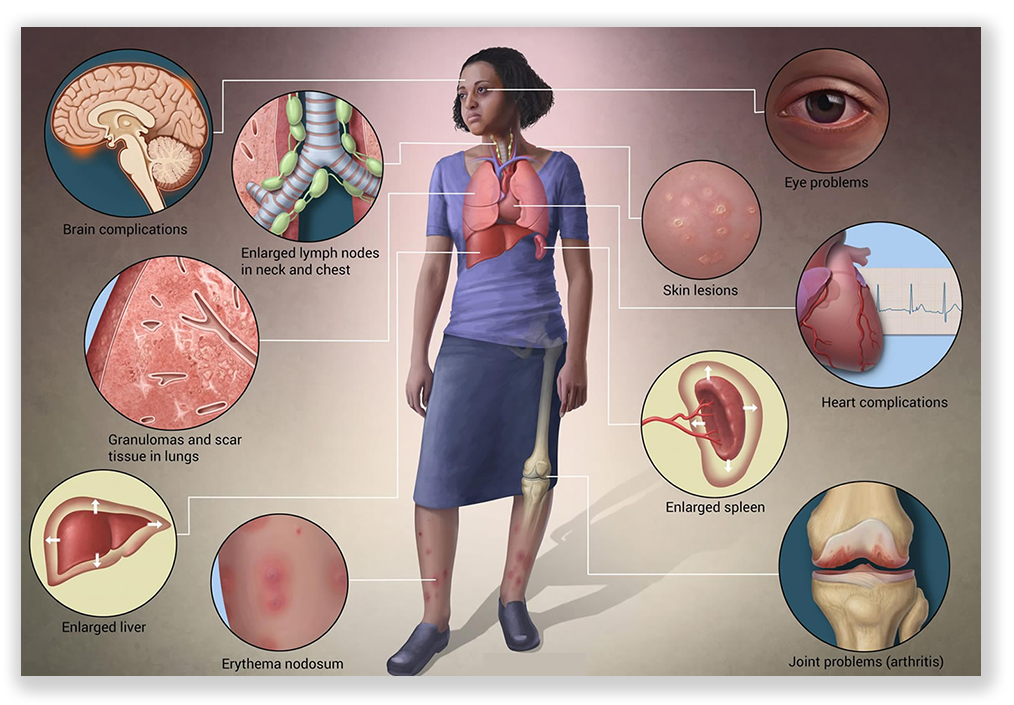

In 2022, Bill moved for compassionate release, citing his sarcodiosis, a chronic condition characterized by inflammation in the lungs and other organs, as justification. His court-appointed an attorney to help Bill, who added an argument that the change in the law provided an independent reason for compassionate release. Bill’s lawyer asked the court to sit on the motion until the new 1B1.13 became effective. When it did, the government agreed that Bill’s medical condition established “extraordinary and compelling” reasons warranting release both alone and combined with other factors.

In 2022, Bill moved for compassionate release, citing his sarcodiosis, a chronic condition characterized by inflammation in the lungs and other organs, as justification. His court-appointed an attorney to help Bill, who added an argument that the change in the law provided an independent reason for compassionate release. Bill’s lawyer asked the court to sit on the motion until the new 1B1.13 became effective. When it did, the government agreed that Bill’s medical condition established “extraordinary and compelling” reasons warranting release both alone and combined with other factors.

Last week, the court reduced Bill’s life sentence to time served (which, considering Bill’s accumulated good time, now equals 15 years.

The district court’s decision is a model of careful scholarship and proper application of the new 1B1.13. The court relies on Sentencing Commission studies to hold that Bill’s sentence

is an outlier among drug trafficking offenders… Federal prosecutors do not uniformly seek § 851 enhancements, so sentences for offenders like him vary considerably… Some judicial districts see § 851 notices filed for as many as 75% of eligible drug trafficking defendants whereas other districts do not see them filed at all. Since most offenders confronted with an enhanced sentence cooperate, a little less than 4% of eligible defendants ultimately face an enhanced penalty at sentencing… Those in the 4% receive prison terms roughly ten years longer than the average sentence for similar offenders who evaded the enhanced penalty, and twelve years longer than the average for eligible offenders against whom the notice was never filed.

The court candidly admitted that Bill “received one of these unusually long sentences as a de facto punishment for not cooperating.” While the court acknowledged that Bill’s sentence could not be completely compared with a 13-year sentence a cooperator with a similar record had received (because Bill did not cooperate and thus did not receive credit for doing so), it noted nonetheless that the differences between the defendants “do not wholly account for the more than twenty-year disparity between a thirteen-year prison term and life behind bars.”

The court observed that Bill “received a sentence at least twenty years longer than the fifteen-year minimum Congress now deems warranted for offenders like him. He had a criminal history category of II, comprised entirely of nonviolent offenses, which would warrant nothing close to a life sentence under the guidelines. Whatever ‘significant period of incarceration’ this Court may have settled on at the original sentencing, had it any discretion back then, would not have come within twenty years of Mr. Vanholten’s remaining life expectancy. A difference of a generation between the actual sentence and the sentence Mr. Vanholten would likely receive today no doubt makes for a gross disparity.”

The court observed that Bill “received a sentence at least twenty years longer than the fifteen-year minimum Congress now deems warranted for offenders like him. He had a criminal history category of II, comprised entirely of nonviolent offenses, which would warrant nothing close to a life sentence under the guidelines. Whatever ‘significant period of incarceration’ this Court may have settled on at the original sentencing, had it any discretion back then, would not have come within twenty years of Mr. Vanholten’s remaining life expectancy. A difference of a generation between the actual sentence and the sentence Mr. Vanholten would likely receive today no doubt makes for a gross disparity.”

Similarly, the court cited medical studies establishing that sarcodiosis fit the new 1B1.13(b)(1)(B) “extraordinary and compelling” reason that a defendant (1) is suffering from a serious physical or medical condition that (2) substantially diminishes the ability of the defendant to provide self-care within the environment of a correctional facility and (3) from which he is not expected to recover. “Though he is not at death’s door,” the court ruled, Bill’s “medical records show that his sarcoidosis is both chronic and persistent, hurting his lungs and pulmonary function. He is unlikely to recover from it. According to the opinion of medical experts, Mr. Vanholten’s morbidity puts him at a heightened risk of a sudden and serious cardiac event, and a decreased life expectancy,” citing medical journals. At the same time, the court relied on Bill’s records showing infrequent consultation with specialists and noted that the Dept. of Justice “makes no secret that the BOP’s chronic medical staffing shortage has made its ability to deliver healthcare a challenge.”

The court released Bill, effective a week from today. Beyond the happy ending for a badly over-sentenced defendant, the court has given prisoners an early Christmas gift, a roadmap for effectively negotiating compassionate release under the new 1B1.13.

The court released Bill, effective a week from today. Beyond the happy ending for a badly over-sentenced defendant, the court has given prisoners an early Christmas gift, a roadmap for effectively negotiating compassionate release under the new 1B1.13.

United States v. Vanholten, Case No. 3:12-cr-96 (M.D. Fla. Dec. 1, 2023), 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 213764

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Application and Impact of 21 U.S.C. § 851: Enhanced Penalties for Federal Drug Trafficking Offenders (2018)

– Thomas L. Root