We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SENTENCING COMMISSION ADOPTS AMENDMENTS

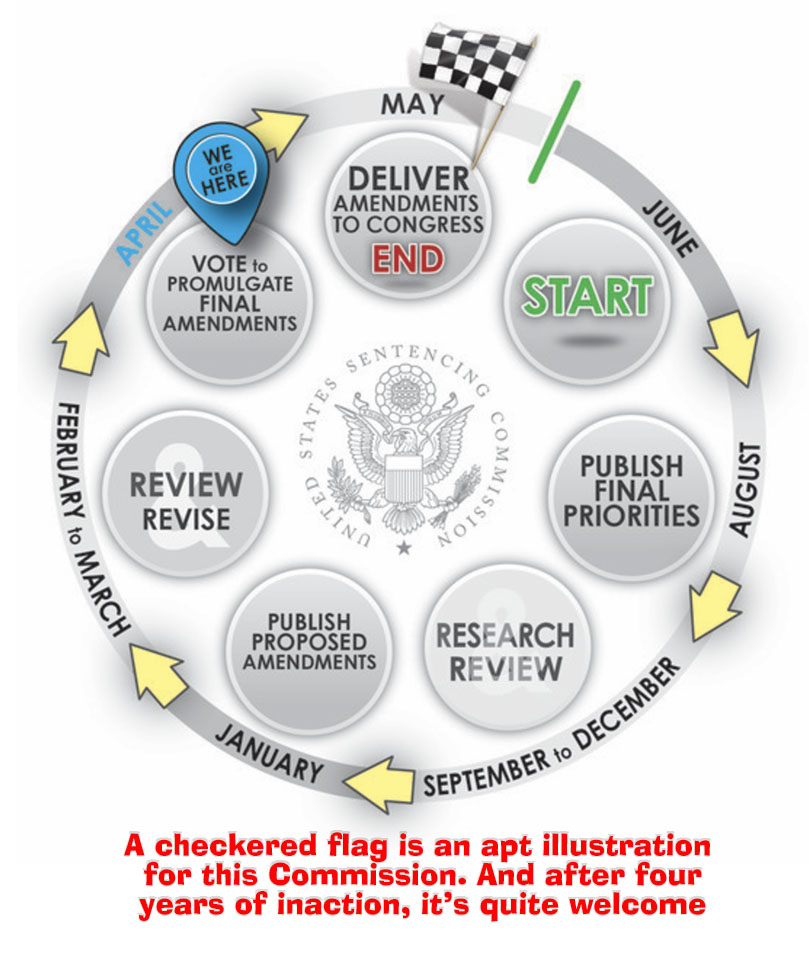

The U.S. Sentencing Commission yesterday adopted proposed amendments to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for the first time in five years, with the new “compassionate release” guidelines consuming much of the meeting and generating sharp (but collegial) disagreement.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission yesterday adopted proposed amendments to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for the first time in five years, with the new “compassionate release” guidelines consuming much of the meeting and generating sharp (but collegial) disagreement.

The “compassionate release” Guideline, USSG § 1B1.13, was approved on a 4-3 vote. It updates and expands the criteria for what can qualify as “extraordinary and compelling reasons” to grant compassionate release – the language in 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) – and it will give judges both more discretion and more guidance to determine when a sentence reduction is warranted.

The new categories that could make an inmate eligible for compassionate release include

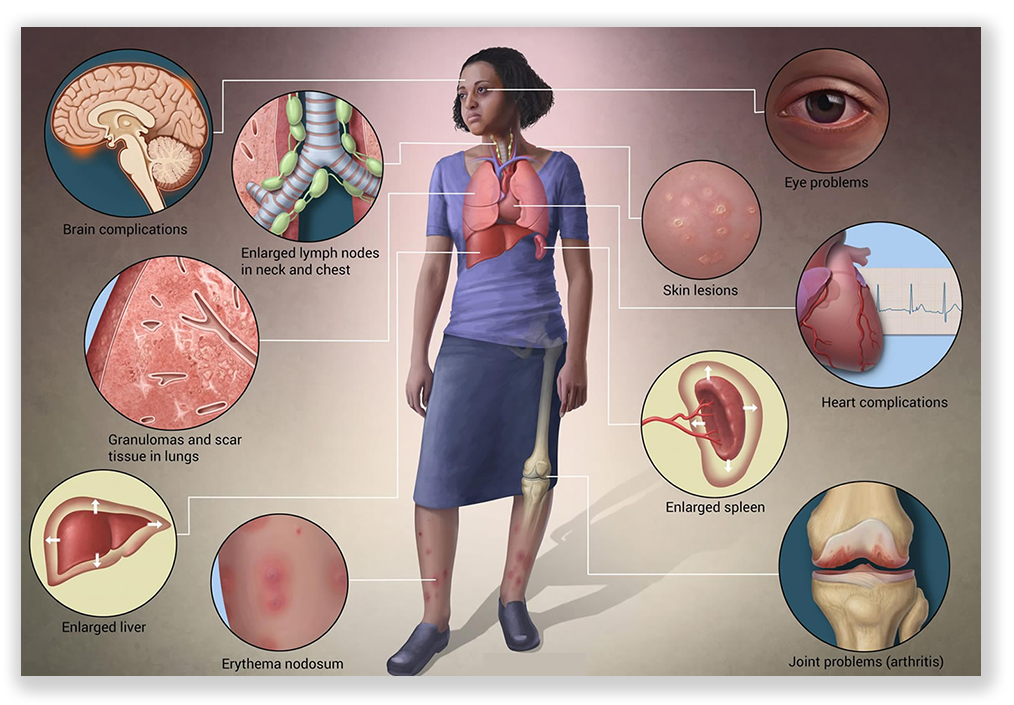

• if the prisoner is suffering from a medical condition that requires long-term or specialized medical care not being provided by the BOP and without which he or she is at risk of serious deterioration in health or death.

• if the prisoner is housed at a prison affected or at imminent risk of being affected by (an ongoing outbreak of infectious disease or an ongoing public health emergency declared by the appropriate federal, state, or local authority, and due to personal health risk factors and custodial status, he or she is at increased risk of suffering “severe medical complications or death as a result of exposure” to the outbreak.

• if the prisoner’s parent is incapacitated and the prisoner would be the only available caregiver.

• if the prisoner establishes that similar family circumstances exist involving any other immediate family member or someone whose relationship with the prisoner is similar in kind to that of an immediate family member when the prisoner would be the only available caregiver.

• if the prisoner becomes the victim of sexual assault by a corrections officer.

• if a prisoner received an unusually long sentence and has served at least 10 years of the term of imprisonment, changes in the law (other than to the Guidelines) may be considered in determining whether an extraordinary and compelling reason exists, but only where such change would produce a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence likely to be imposed at the time the motion is filed.

The amendments also provide that while rehabilitation is not, by itself, an extraordinary and compelling reason, it may be considered in combination with other circumstances.

Three of the seven-member Commission disagreed sharply with the “unusually long sentence” amendment. Commissioner Candice C. Wong said, “Today’s amendment allows compassionate release to be the vehicle for applying retroactively the very reductions that Congress has said by statute should not apply retroactively.”

Three of the seven-member Commission disagreed sharply with the “unusually long sentence” amendment. Commissioner Candice C. Wong said, “Today’s amendment allows compassionate release to be the vehicle for applying retroactively the very reductions that Congress has said by statute should not apply retroactively.”

Commissioner Claira Boom Horn, who is a sitting US District Court Judge in Kentucky, observed that “nothing in the First Step Act – literally nothing, not text, not legislative history – indicates any intention on Congress’s part to expand the substantive criteria for granting compassionate release, much less to fundamentally change the nature of compassionate release to encompass for the first time factors other than the defendant’s personal or family circumstances. The Supreme Court tells us that Congress does not hide elephants in mouseholes and it did not do so here.”

Commissioner Claire McCusker Murray said, “The seismic expansion of compassionate release promulgated today not only saddles judges with the task of interpreting a free will catch-all but also ensures a flood of motions, a flood that will then repeat anytime there is a nonretroactive change in the law. For the past several years, while the Commission lacked a quorum to implement the First Step Act, the country has experienced a natural experiment in what happens when judges have no operative guidance as to the criteria they should apply in deciding release motions. The result has been widespread disparities. In Fiscal Year 2022, for example, the most generous circuit granted 35% of compassionate release motions, the most cautious granted only 2.5%. The disparities within circuits and even within courthouses were often just as stark. We fear that with today’s dramatic vague and ultimately unlawful expansion of compassionate release that we… will expect far more of the same.”

Commissioner John Gleeson, a retired US District Court judge and Wall Street law firm partner, disagreed: “[The amendment’s] common sense guidance is fully consistent with separation of powers principles, our authority as the Sentencing Commission, and with the First Step Act. Most importantly, it will ensure that § 3582(c)(1)(A) of Title 18 of the United States Code serves one of the purposes Congress explicitly intended it to serve when that law is enacted almost 40 years ago: to provide a needed transparent judicial second look at unusually long sentences that in fairness should be reduced.”

Congress may veto one or more of the Guidelines proposals between now and November 1, 2023. That has only once before, when Congress voted down a guideline lessening the crack/cocaine disparity in 2005. Congress is pretty busy, and both the Senate and House are pretty evenly split politically, but the extent of the disagreement at the Commission gives cause for concern. If Congress does veto, it is unclear whether would focus solely on the “unusually long sentence” subsection of new § 1B1.13, or whether the entire amended Guideline would be jettisoned.

Congress may veto one or more of the Guidelines proposals between now and November 1, 2023. That has only once before, when Congress voted down a guideline lessening the crack/cocaine disparity in 2005. Congress is pretty busy, and both the Senate and House are pretty evenly split politically, but the extent of the disagreement at the Commission gives cause for concern. If Congress does veto, it is unclear whether would focus solely on the “unusually long sentence” subsection of new § 1B1.13, or whether the entire amended Guideline would be jettisoned.

In other action, the Commission had been considering an amendment that prohibited courts from imposing longer sentences based on alleged crimes of which a defendant had been acquitted. Commission Chairman Carleton Reeves, a federal district judge from the Southern District of Mississippi, said the Commission needs more time before making a final determination on the issue.

Reuters reported that Michael P. Heiskell, President-Elect of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, said he was disappointed by the delay. “Permitting people to be sentenced based on conduct for which a jury has acquitted them is fundamentally unfair because it eviscerates the constitutional right to trial and disrespects the jury’s role,” he said in a statement.

However, the Commission’s delay may rejuvenate the McClinton v. United States petition for certiorari, which the Supreme Court has been sitting on at the suggestion of the Dept of Justice, awaiting Sentencing Commission action on acquitted conduct. A Supreme Court decision that use of acquitted conduct in sentencing is unconstitutional would benefit many more people than would a prospective Guidelines change.

The USSC also adopted a criminal history amendment that eliminates “status points” (sometimes called “recency points”) – additional criminal history points assessed if the defendant committed the current crime within two years of release for a prior crime – and grants a 2-level downward adjustment to a defendant’s offense level if he or she had zero criminal history points and met other criteria.

The Commission also approved an amendment to criminal history commentary advising judges to treat prior marijuana possession offenses more leniently in the criminal history calculus, making downward adjustments for offenses now seen as lawful by many states.

The proposal doesn’t seek to remove marijuana convictions as a criminal history factor entirely, but it would revise commentary within the guidelines to “include sentences resulting from possession of marihuana offenses as an example of when a downward departure from the defendant’s criminal history may be warranted,” according to a synopsis.

None of the Guidelines changes is retroactive without specific Commission determination that they should be. The USSC yesterday issued a notice that it will consider, pursuant to 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) and 28 USC § 994(u), whether Guidelines changes on “status points” and the “zero criminal history points” adjustment should be retroactive, and ask for public comment on the matter.

None of the Guidelines changes is retroactive without specific Commission determination that they should be. The USSC yesterday issued a notice that it will consider, pursuant to 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) and 28 USC § 994(u), whether Guidelines changes on “status points” and the “zero criminal history points” adjustment should be retroactive, and ask for public comment on the matter.

Although the Guidelines amendments do not become effective until November, most federal circuits have declared that – while the current § 1B1.13 is not binding on district courts because it is pre-First Step – courts should consider it to express the opinion of an agency expert in sentencing. The amended § 1B1.13 has every bit of the authority that the current non-binding § 1B1.13 has, and it has the additional benefit of being evidence of current Sentencing Commission thought.

USSC, Adopted Amendments (Effective November 1, 2023) (April 5, 2023)

USSC, Issue For Comment On Retroactivity Of Criminal History Amendment (April 5, 2023)

Reuters, U.S. panel votes to expand compassionate release for prisoners (April 5, 2023)

Marijuana Moment, Federal Sentencing Commission Approves New Marijuana Guidelines For Judges To Treat Past Convictions More Leniently (April 5, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root

The district court turned him down because caring for a parent was not defined in the old USSG § 1B1.13 as a basis for compassionate release at the time Quinton applied as an extraordinary and compelling reason for an 18 USC § 3582(c)(1) sentence reduction. The § 1B1.13 that became effective on Nov 1, 2023, however, does recognize parent care as an extraordinary and compelling reason.

The district court turned him down because caring for a parent was not defined in the old USSG § 1B1.13 as a basis for compassionate release at the time Quinton applied as an extraordinary and compelling reason for an 18 USC § 3582(c)(1) sentence reduction. The § 1B1.13 that became effective on Nov 1, 2023, however, does recognize parent care as an extraordinary and compelling reason. Of course, the Circuit could just as easily have remanded Quinton’s case to the district court for application of the new § 1B1.13 standard to the factual record. But that would have saved time and paperwork.

Of course, the Circuit could just as easily have remanded Quinton’s case to the district court for application of the new § 1B1.13 standard to the factual record. But that would have saved time and paperwork. The Circuit complained that the district court “did not have the opportunity to consider that sex offenders who have sexually abused children are a threat to continue doing so” because of the alleged high recidivism of sex offenders (a myth from 20 years ago that even the DOJ has renounced). Of course the district court did not: Circuit precedent dictated that it need not do so. Nevertheless, the 11th clearly gave the district court marching orders on how to decide this issue if Quinton came back with a new motion.

The Circuit complained that the district court “did not have the opportunity to consider that sex offenders who have sexually abused children are a threat to continue doing so” because of the alleged high recidivism of sex offenders (a myth from 20 years ago that even the DOJ has renounced). Of course the district court did not: Circuit precedent dictated that it need not do so. Nevertheless, the 11th clearly gave the district court marching orders on how to decide this issue if Quinton came back with a new motion.