We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

TRUMP MANAGES TO MAKE CLEMENCY EVEN CRAZIER

The rolling waves of pardons and commutations emanating from the White House seem like good news to federal prisoners, who are filing clemency petitions to get in on the frenzy. Think Robinhood investors piling into a meme stock…

The rolling waves of pardons and commutations emanating from the White House seem like good news to federal prisoners, who are filing clemency petitions to get in on the frenzy. Think Robinhood investors piling into a meme stock…

Over the past several weeks, President Donald Trump has issued a wave of pardons and sentence reductions to dozens of people. That’s good news. The bad news is that the recipients of Trump’s largesse are largely political allies, campaign donors, law enforcement officials, and Republican politicians.

I won’t try to recount them all, people from crooked cops to digital dope peddlers to gang bangers to celebrity fraudsters. Even George Floyd murderer Derek Chauvin and accused sex monster and rapper Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs are being talked about as candidates for Trumpian clemency largesse. Instead, I’ll look at the lessons to be derived from the freedom frenzy:

The three sure-fire ways to get clemency from this Administration are (1) to be a rabid Trump supporter, (2) to have millions to spend, or (3) to know someone who knows someone who knows someone in Trump’s inner circle.

For more than a century, career civil servants led the Dept of Justice Office of Pardon Attorney, evaluating clemency petitions based on legal and humanitarian criteria that were criticized for the glacial review pace, too much DOJ input, and opaque and sometimes inconsistent decisions. But now, newly appointed Pardon Attorney Ed Martin, a vigorous MAGA partisan, “has begun turning the office into a new pipeline for political allies to get their cases in front of Trump,” the Wall Street Journal reported last week.

For more than a century, career civil servants led the Dept of Justice Office of Pardon Attorney, evaluating clemency petitions based on legal and humanitarian criteria that were criticized for the glacial review pace, too much DOJ input, and opaque and sometimes inconsistent decisions. But now, newly appointed Pardon Attorney Ed Martin, a vigorous MAGA partisan, “has begun turning the office into a new pipeline for political allies to get their cases in front of Trump,” the Wall Street Journal reported last week.

Martin unabashedly described his pardon approach last week on X: “No MAGA left behind.”

Martin said he is working closely with Alice Johnson, the White House pardon czar whom Trump pardoned of drug offenses during his first term. That’s good news. The bad news is Martin’s approach: “The message should be clear that we’re sticking by people that do good things and the right things.”

Martin’s first pardon recommendation, adopted by Trump last week, was Scott Jenkins, the former sheriff of Culpeper County, Virginia. Jenkins was to report to prison last week after being convicted of selling no-show auxiliary sheriff’s deputy positions for over $75,000 in bribes. The evidence included videos of the sheriff accepting bags of cash and testimony of some of the people who bought the badges. He was sentenced to 120 months.

Martin’s first pardon recommendation, adopted by Trump last week, was Scott Jenkins, the former sheriff of Culpeper County, Virginia. Jenkins was to report to prison last week after being convicted of selling no-show auxiliary sheriff’s deputy positions for over $75,000 in bribes. The evidence included videos of the sheriff accepting bags of cash and testimony of some of the people who bought the badges. He was sentenced to 120 months.

But as the Bulwark explained last week, “Jenkins was a rabidly anti-immigrant, pro-Trump sheriff who’d become a minor celebrity in MAGA world. Trump himself may not have known of him, but Ed Martin did… Martin celebrated his achievement just after the pardon: ‘Thank you, President Trump! I am thrilled that Sheriff Jenkins is the first pardon since I became your Pardon Attorney.’”

For those not connected to MAGA, seeking clemency “has become big business for lobbying and consulting firms close to the administration, with wealthy hopefuls willing to spend millions of dollars for help getting their case in front of the right people,” a lobbyist told NBC News. “From a lobbying perspective, pardons have gotten profitable.”

Two people directly familiar with proposals to lobbying firms said they knew of a client who’d offered $5 million to help get a case to Trump. “Cozying up to a president’s allies or hiring lobbyists to gain access to clemency isn’t new,” NBC said. “But along with the price spike, what’s different now is that Trump is issuing pardons on a rolling basis — rather than most coming at the end of the administration.”

Two people directly familiar with proposals to lobbying firms said they knew of a client who’d offered $5 million to help get a case to Trump. “Cozying up to a president’s allies or hiring lobbyists to gain access to clemency isn’t new,” NBC said. “But along with the price spike, what’s different now is that Trump is issuing pardons on a rolling basis — rather than most coming at the end of the administration.”

“It’s like the Wild West,” a Trump ally and lobbyist said. “You can basically charge whatever you want.”

But what about Alice Johnson, appointed as Pardon Czar to bring worthy clemency candidates to President Trump? Is that working?

Alice apparently was instrumental in bringing reality TV stars and celebrity whiners Todd and Julie Chrisley to Trump for full pardons of their bank and tax fraud convictions. Todd stayed in the headlines for the 24 months he served of his 12-year sentence by claiming, among other things, that FPC Pensacola was “literally” starving inmates to death, that the prisoners were forced to live in filth and eat contaminated food, and that he “feared for his life.”

“I know not only their stories, but I make sure that I’m selecting people who have either been rehabilitated, who pose no safety risk, and also we look at cases where there has been obvious weaponization against these individuals,” Alice Johnson told NewsNation Now. She was quoted in Eonline as saying “The celebrity part really didn’t play a role in this… These are everyday Americans who deserve a second chance,” she continued. “I’ve really been looking at those who pose no safety risk, don’t have victims of violent crimes. These people need to be returned to their families. They really get a chance to have a second shot at life.”

A month ago, Trump pardoned Paul Walczak, a former nursing home executive sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered to pay more than $4 million in restitution for tax crimes. The pardon came after Walczak’s mom, a GOP donor, Walczak’s pardon has received attended a $1-million-per-person fundraising dinner at Mar-a-Lago, the New York Times reported.

A month ago, Trump pardoned Paul Walczak, a former nursing home executive sentenced to 18 months in prison and ordered to pay more than $4 million in restitution for tax crimes. The pardon came after Walczak’s mom, a GOP donor, Walczak’s pardon has received attended a $1-million-per-person fundraising dinner at Mar-a-Lago, the New York Times reported.

Even some of the people who are not rich or famous are lucky enough to get in on the act. An “everyday American” prisoner who was not a Chrisley but received clemency last week was serving a 50-year sentence for healthcare fraud. One of his co-defendants, however, had been Alice Johnson’s cellie at FCI Aliceville. Alice got her sprung in 2020. Five years later, the co-defendant lobbied Alice to get him out, too.

I helped him with his clemency petition a few years ago, a 100-page tome. No doubt he deserved clemency but no more or less than countless others whose conspiracies did not include someone who became Alice’s cellmate.

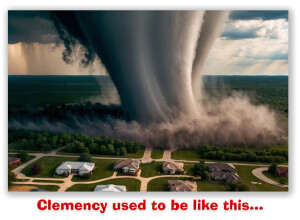

Ultimately, it’s depressing. Clemency has always been like a tornado tearing through a neighborhood, taking some lucky inmates seemingly at random while leaving others in their bunks to serve out their time. Now, there isn’t even a randomness factor anymore, a sense among prisoners that maybe, despite the ordinariness of their offense or their families’ quotidian circumstances, they may be the beneficiaries of a Presidential act of grace.

Ultimately, it’s depressing. Clemency has always been like a tornado tearing through a neighborhood, taking some lucky inmates seemingly at random while leaving others in their bunks to serve out their time. Now, there isn’t even a randomness factor anymore, a sense among prisoners that maybe, despite the ordinariness of their offense or their families’ quotidian circumstances, they may be the beneficiaries of a Presidential act of grace.

Now, it’s all about loyalty, wealth, connections.

We’re in a different clemency world than ever before, but the average federal inmate is further from fair consideration than ever.

CNN, ‘No MAGA left behind’: Trump’s pardons get even more political (May 28, 2025)

NBC, Trump pardons drive a big, burgeoning business for lobbyists (May 31, 2025)

Washington Post, Trump’s clemency spree extends to ex-gangster, rapper, former congressmen (May 29, 2025)

The Bulwark, Trump’s Dangerous Pardon Power (May 27, 2025)

Pensacola News Journal, Todd Chrisley served sentence at Pensacola Federal Prison Camp before pardon. What to know (May 28, 2025)

New York Times, Trump Pardoned Tax Cheat After Mother Attended $1 Million Dinner (May 27, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root