We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE NAVARRO CONUNDRUM

Sharp-eyed reader Drew wrote last week to ask about the United States Sentencing Commission’s proposal to change the supervised release guidelines.

Supervised release – a term of post-incarceration control over a former prisoner by the US Probation Office during which the ex-inmate can be sent back to prison for violations of a whole list of conditions – is imposed as a part of nearly every sentence, despite the fact that “it is required in fewer than half of federal cases,” according to one federal judge. No one subjected to it especially likes it, which is why many have cheered the Sentencing Commission’s proposal to reduce its usage.

Supervised release – a term of post-incarceration control over a former prisoner by the US Probation Office during which the ex-inmate can be sent back to prison for violations of a whole list of conditions – is imposed as a part of nearly every sentence, despite the fact that “it is required in fewer than half of federal cases,” according to one federal judge. No one subjected to it especially likes it, which is why many have cheered the Sentencing Commission’s proposal to reduce its usage.

The proposed amendment now being considered would amend USSG § 5D1.1 to remove the requirement that a court reflexively impose a term of supervised release whenever a sentence of imprisonment of more than one year is imposed, so a court would be required to impose supervised release only when required by statute. For cases in which the decision to impose supervised release is discretionary, the court would be directed to impose it “when warranted by an individualized assessment of the need for supervision,” which the court would be expected to explain on the record.

Who could possibly complain about avoiding a term of supervised release, a period of post-incarceration control that, by some accounts, violates one-third of the people subjected to it?

Remember Peter Navarro, once a confidante of first-term President Trump and currently his Senior Counselor for Trade and Manufacturing? Petey suffered hideously as a federal prisoner for four whole months at FCI Miami in between his last and current White House gigs, doing time after being convicted of contempt of Congress.

You’re wondering, of course, who could possibly hold Congress in contempt? Besides almost all of America, that is? Well, Pete did by refusing to testify before the House January 6th Committee. He was sentenced to four whole months of incarceration. Last summer, as his endless sentence drew to a close, Pete petitioned his sentencing court for compassionate release under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A), asking not that his sentence be cut but instead that the court add a few days of supervised release.

It was subtraction by addition. Pete wanted a few days of supervised release added to his sentence because of a quirk in the First Step Act. Under the Act, FSA credits – time credits that are earned for successful completion of programming intended to reduce recidivism – can be used for early release or halfway house/home confinement benefits. The Bureau of Prisons credits the initial FSA credits a prisoner earns to decrease the length of his or her sentence by up to a year under 18 USC § 3624(g)(3), but only if the prisoner has had a term of supervised release imposed as part of his sentence.

Generally, the supervised release condition has not been a problem for prisoners because courts hand out supervised release like red MAGA caps at a Trump rally. However, a few sentences don’t have supervised release added to the tag end, such as very short ones or cases where an alien will be deported at the end of his term.

Generally, the supervised release condition has not been a problem for prisoners because courts hand out supervised release like red MAGA caps at a Trump rally. However, a few sentences don’t have supervised release added to the tag end, such as very short ones or cases where an alien will be deported at the end of his term.

That happened to Pete, whose court imposed a four-month prison sentence without any supervised release afterward. This left Pete unable to use any of the 14-odd days of FSA credit he had earned to go home a couple of weeks early.

Pete’s creative legal team filed for the sentence non-reduction under § 3582(c)(1)(A), asking that the sentence be modified to add a little supervised release after Mr. Navarro’s four months in hell ended. The court didn’t bite, holding that the sine qua non of a sentence reduction motion was a request for an actual sentence reduction. Pete had asked for a sentence increase, and that could not be granted.

As a result, Pete barely made it out of his personal Devil’s Island in time to be flown by private jet to the Republican Convention in Milwaukee. (Incidentally, he emerged from prison as a dedicated BOP reformer, but that commitment seems to have waned since he made it back to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW).

The Navarro episode illustrated Drew’s question: If supervised release were to be no longer imposed for many offenses, would that not also hobble a prisoner’s ability to earn the up-to-one-year-off that § 3624(g)(3) offers? Darn right – just ask President Trump’s Special Counselor on Trade and Manufacturing. Is this the USSC sneakily trying to take benefits away from some prisoners? Might the result of the proposed amendment’s adoption be a repeat of year-and-a-day sentences where judges impose a day of supervised release in order to allow defendants the full benefit of their FSA credits?

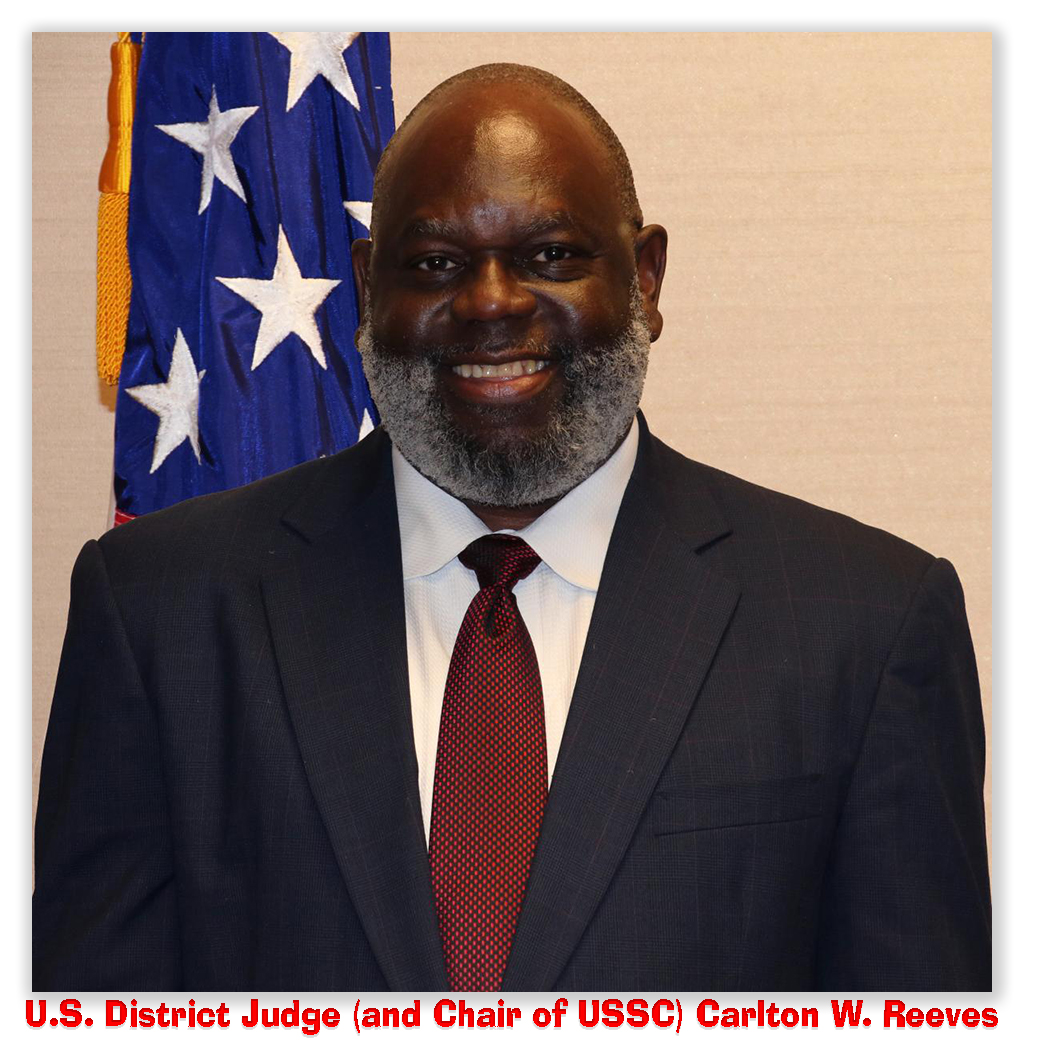

I suspect the Commission simply has not focused on the effect that its proposal would have on prisoners using FSA credits for shorter sentences under 18 USC § 3624(g)(3). The arcane FSA credit regime is not a matter that’s necessarily in the Sentencing Commission’s wheelhouse. The USSC’s proposal to encourage more judicious imposition of supervised release terms is generally laudable: it conserves US Probation Office resources to be spent on people who really need the post-prison supervision while will improve – rather than limit – rehabilitation for many.

(Examples: I had a fellow on supervised release tell me last week that a major trucking firm had been happy to hire him as a long-haul trucker despite his 20 years served for a drug offense until it learned he was still on supervised release. The company told him it could not hire him as long as he was on a US Probation Office tether but to call them the second he was done with supervised release, whereupon they’d be glad to put him in one of their rigs. I had another guy tell me that he couldn’t get life insurance to protect his wife and kids until he was off supervised release. Neither of these limitations helps a former prisoner re-integrate.)

(Examples: I had a fellow on supervised release tell me last week that a major trucking firm had been happy to hire him as a long-haul trucker despite his 20 years served for a drug offense until it learned he was still on supervised release. The company told him it could not hire him as long as he was on a US Probation Office tether but to call them the second he was done with supervised release, whereupon they’d be glad to put him in one of their rigs. I had another guy tell me that he couldn’t get life insurance to protect his wife and kids until he was off supervised release. Neither of these limitations helps a former prisoner re-integrate.)

We’ll have to see whether USSC tweaks its proposal to account for the unforeseen Navarro consequence when the final amendment package is adopted in April.

United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines for United States Courts, 90 FR 8968 (February 4, 2025)

United States v. Thomas, 346 FSupp3d 326 (EDNY 2018)

Order, United States v. Navarro, ECF 176, Case No 22-cr-0200 (DDC, May 15, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root