We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

RUMORS: WILL DEPT OF JUSTICE GO AFTER NEW COMPASSIONATE RELEASE GUIDELINE?

Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman wrote last week in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog that he has “heard talk that, notwithstanding the text of § 994(t), the Justice Department is planning to contest the new [compassionate release] guideline once it becomes effective on November 1.”

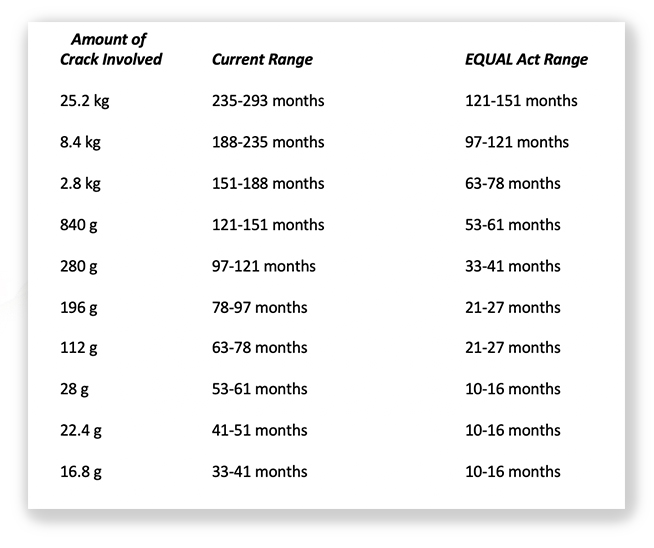

Prof Berman does not cite his sources, but his credentials as among the premier federal sentencing law experts in the nation suggest that his report should be taken seriously. The Dept of Justice was adamantly opposed to the new USSG § 1B1.13(b)(6) – which directs that if a defendant has served at least 10 years of an unusually long sentence, a change in the law (other than a non-retroactive Guideline amendment) “may be considered in determining whether the defendant presents an extraordinary and compelling reason, but only where such change would produce a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence likely to be imposed at the time the motion is filed, and after full consideration of the defendant’s individualized circumstances.” In fact, subsection (b)(6) was the cause of the Sentencing Commission’s extended debate and 4-3 vote split on approving 1B1.13.

Prof Berman does not cite his sources, but his credentials as among the premier federal sentencing law experts in the nation suggest that his report should be taken seriously. The Dept of Justice was adamantly opposed to the new USSG § 1B1.13(b)(6) – which directs that if a defendant has served at least 10 years of an unusually long sentence, a change in the law (other than a non-retroactive Guideline amendment) “may be considered in determining whether the defendant presents an extraordinary and compelling reason, but only where such change would produce a gross disparity between the sentence being served and the sentence likely to be imposed at the time the motion is filed, and after full consideration of the defendant’s individualized circumstances.” In fact, subsection (b)(6) was the cause of the Sentencing Commission’s extended debate and 4-3 vote split on approving 1B1.13.

Any DOJ litigation attack on 1B1.13 makes little sense. Congress has decreed in 28 USC 994(t) that the Sentencing Commission “shall describe what should be considered extraordinary and compelling reasons for sentence reduction, including the criteria to be applied and a list of specific examples.” What’s more, Congress has built a veto mechanism into the Guidelines, giving legislators 180 days to reject what the USSC does before it becomes effective. It would be tough to argue that § 994(t) and the fact that Congress let the new 1B1.13 go into effect didn’t mean that any DOJ effort to convince a court to invalidate the new Guideline is doomed to failure.

The rumor may be stoked by a USA Today article last week that warned that “new Sentencing Commission guidelines will give [prisoners] a chance for compassionate release. But DOJ threatens to stand in the way.” The authors wrote that

[t]he Sentencing Commission’s commonsense expansion of compassionate release makes us hopeful that our federal criminal system can carve out a little space for redemption, mercy and a recognition that we don’t always get it right the first time around. Unfortunately, even with the promise of and need for the commission’s new guidance, the future of compassionate release is uncertain. The Department of Justice has objected to the commission’s recognition that legal changes resulting in an unjust sentence can qualify as an extraordinary and compelling reason justifying relief.

The article cites the DOJ’s spirited opposition to what became 1B1.13(b)(6) – the “change in the law” provision” – of the compassionate release Guideline. But nothing in the DOJ’s opposition comments, which it was perfectly entitled to file, suggests that the government will try to get the amendment set aside judicially.

The USA Today article argued that

the commission’s ‘unusually long sentences’ provision is good policy. Far from a get-out-of-jail-free card, as some have suggested, it is instead a narrow recognition that a sentence imposed decades ago may, upon review today, be longer than necessary. The provision applies in limited instances where, among other things, the person has served at least 10 years in prison and there is a ‘gross disparity’ between their sentence and the one likely to be imposed today. Even then, an individual still must demonstrate that they will not pose a danger to the community and that their individualized circumstances weigh in favor of a sentence reduction….

Bottom line: I doubt that DOJ plans any omnibus attack on 1B1.13(b)(6). Rather, I suspect that the USA Today authors are extrapolating from the Department’s negative comments during the Guidelines amendment process. Nevertheless, no one’s gone broke yet betting that the DOJ will not be both creative and vigorous in fighting to keep people locked up in order to honor a draconian but lawful sentence.

If Professor Berman seems a little alarmist to you, recall Sen. Barry Goldwater’s famous observation that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. Moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” For now, I stand with the Professor.

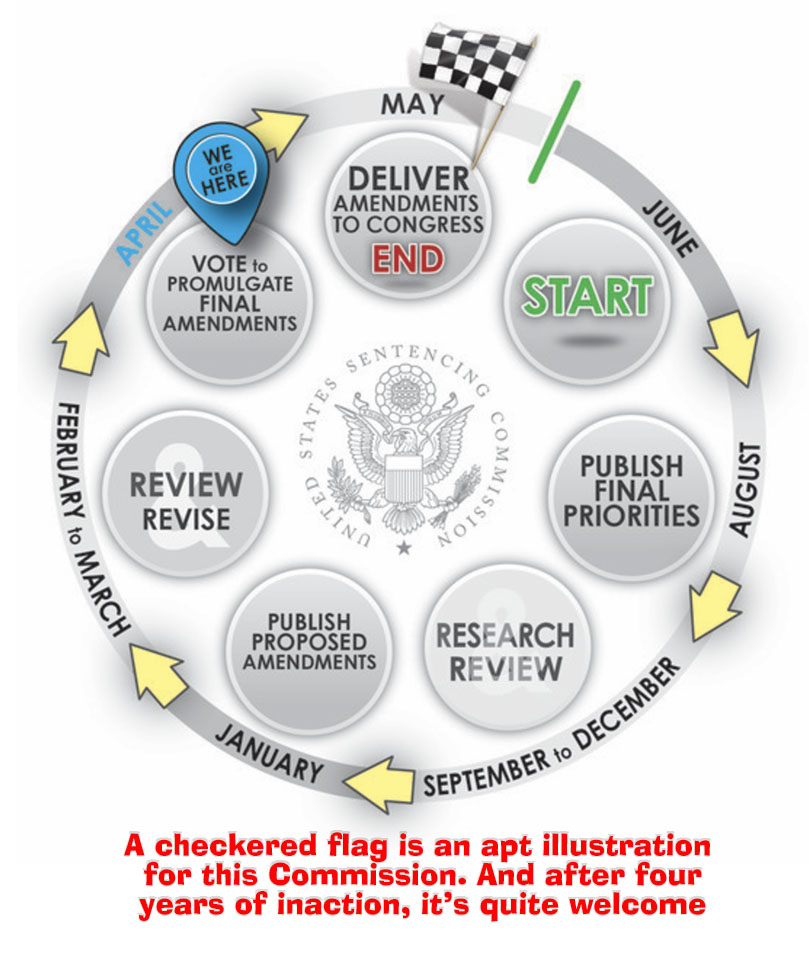

In other Sentencing Commission news, President Joe Biden last week nominated current federal judge Claria Boom Horn (who sits in both the Eastern and Western Districts of Kentucky) and retired federal judge John Gleeson to full 6-year terms on the Commission. Both of them – who were filling one-year interim terms on the USSC – are intelligent and thoughtful commissioners. I see Judge Gleeson – author of what came to be known as the “Holloway motion” when he used his legal and persuasive authority to correct a grossly unjust sentence – to be a little better rounded on sentencing policy.

In other Sentencing Commission news, President Joe Biden last week nominated current federal judge Claria Boom Horn (who sits in both the Eastern and Western Districts of Kentucky) and retired federal judge John Gleeson to full 6-year terms on the Commission. Both of them – who were filling one-year interim terms on the USSC – are intelligent and thoughtful commissioners. I see Judge Gleeson – author of what came to be known as the “Holloway motion” when he used his legal and persuasive authority to correct a grossly unjust sentence – to be a little better rounded on sentencing policy.

That being said, one only has to remember former Commissioner Judge Danny Reeves, Bill Otis and Judge Henry Hudson to realize that the weakest commissioner on the USSC now (and I do not mean to imply that the weakest commission is either Judge Horn or Judge Gleeson) stands far above the ones President Trump favored but was unsuccessful in placing on the Commission.

Sentencing Law and Policy, Urging the Justice Department to respect the US Sentencing Commission’s new guidelines for compassionate release (October 18, 2023)

USA Today, First Step Act advanced prison reform, but hundreds are still serving unjust sentences (October 18, 2023)

White House, President Biden Names Fortieth Round of Judicial Nominees and Announces Nominees for U.S. Attorney, U.S. Marshal, and the U.S. Sentencing Commission (October 18, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root