We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

HABEAS MABEAS?

The Trump Administration continues to underscore its dedication to constitutional rights.

A week ago, President Trump was asked on NBC’s Meet the Press whether US citizens and noncitizens alike had 5th Amendment due process rights. “I don’t know,” the President replied. “I’m not, I’m not a lawyer. I don’t know.”

A week ago, President Trump was asked on NBC’s Meet the Press whether US citizens and noncitizens alike had 5th Amendment due process rights. “I don’t know,” the President replied. “I’m not, I’m not a lawyer. I don’t know.”

Trump said he has “brilliant lawyers… and they are going to obviously follow what the Supreme Court said.” He complained that he was trying to deport “some of the worst, most dangerous people on Earth… I was elected to get them the hell out of here, and the courts are holding me from doing it.”

In other words, what a President perceives to be his mandate trumps (no pun intended) constitutional protections.

Last Friday, White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller said that the White House is “actively looking at” suspending habeas corpus as part of the administration’s immigration crackdown:

Well, the Constitution is clear — and that of course is the supreme law of the land — that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in a time of invasion. So, it’s an option we’re actively looking at. Look, a lot of it depends on whether the courts do the right thing or not.

Habeas corpus dates predates medieval English common law. It requires law enforcement to justify detaining people and produce those people before a judge so their cases can be reviewed. Federally, the right is exercised through 28 USC §§ 2241 and 2255. The Constitution’s Suspension Clause allows habeas corpus to be suspended only “in cases of rebellion or invasion [when] the public Safety may require it.”

Habeas corpus dates predates medieval English common law. It requires law enforcement to justify detaining people and produce those people before a judge so their cases can be reviewed. Federally, the right is exercised through 28 USC §§ 2241 and 2255. The Constitution’s Suspension Clause allows habeas corpus to be suspended only “in cases of rebellion or invasion [when] the public Safety may require it.”

Of course, the White House is suggesting that habeas corpus would be suspended only for immigrants here illegally. The problem is this: ICE sweeps up someone it says is an illegal immigrant. That person has no right to challenge the accusation before being whisked out of the country. My barber, a guy whose family has been in this country for at least 150 years, told me the other day that he didn’t see why illegal immigrants should have any constitutional protections whatsoever. My question to him was, “So what if ICE bursts into your shop and grabs you, alleging that you’re an illegal immigrant. What do you do then, if you can’t petition the court for a hearing at which ICE has to prove you’re not dyed-in-the-wool-American born-in-the-USA Bob the Barber?”

He thought about that but concluded, “No, they’d never do that.”

Right.

A suspension of habeas corpus would mean the Trump administration could detain people believed to be noncitizens without letting them challenge that detention or to deport noncitizen prisoners without giving them access to §§ 2241 or 2255 proceedings or to immigration courts.

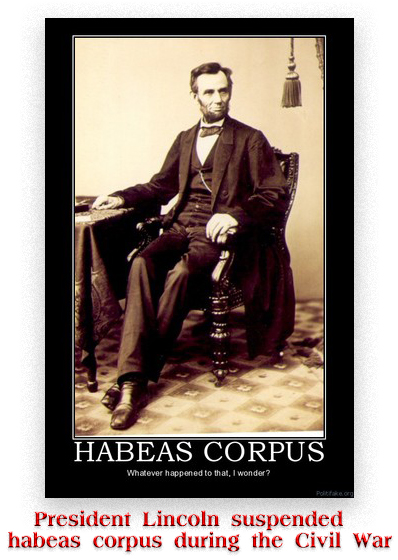

Habeas corpus has been suspended only four times in American history, and each time Congress has authorized the suspension. (In the case of the Civil War, President Limcoln suspended habeas corpus first, but Congress caught up with the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, 12 Stat. 755 (1863), that authorized Lincoln’s suspension after the fact).

Habeas corpus has been suspended only four times in American history, and each time Congress has authorized the suspension. (In the case of the Civil War, President Limcoln suspended habeas corpus first, but Congress caught up with the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, 12 Stat. 755 (1863), that authorized Lincoln’s suspension after the fact).

The National Constitution Center has observed that the Constitution is vague when it comes to “who in the government can suspend the writ of habeas corpus, but it is commonly believed that only Congress can do so,” Forbes said last week. “That means it’s likely Trump would face legal challenges if he decided to suspend the writ of habeas corpus on his own without Congress… but it remains to be seen how the courts could rule.”

New York Times writer Maggie Haberman told CNN that the habeas corpus suspension proposal is an attempt to put the federal courts on notice: “Some of this might just be fear. A, it’s a way to intimidate the courts, which we have seen Trump and Stephen Miller do, a lot of, they’ve been criticizing judges routinely and repeatedly… It also might be to scare migrants and to get migrants to leave.”

New York Times writer Maggie Haberman told CNN that the habeas corpus suspension proposal is an attempt to put the federal courts on notice: “Some of this might just be fear. A, it’s a way to intimidate the courts, which we have seen Trump and Stephen Miller do, a lot of, they’ve been criticizing judges routinely and repeatedly… It also might be to scare migrants and to get migrants to leave.”

Boston Globe, Trump, in a new interview, says he doesn’t know if he backs due process rights (May 4, 2025)

The Hill, White House ‘actively looking’ at suspending habeas corpus in immigration crackdown (May 9, 2025)

National Constitution Center, The Suspension Clause (2025)

Forbes, Stephen Miller Suggests Trump Administration Could Suspend Habeas Corpus To Detain Immigrants—Here’s What That Means (May 9, 2025)

The Hill, Haberman: Threat to nix habeas corpus just a way to ‘intimidate courts,’ ‘scare migrants’ (May 10, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root

The BOP probably doesn’t like that big white bear, the fact that it is required to deliver on RRC placement despite the agency’s utter failure over five years to ensure that there was enough RRC space. But as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy (or both) figured out, just because you can force yourself to not think about it doesn’t mean it isn’t there.

The BOP probably doesn’t like that big white bear, the fact that it is required to deliver on RRC placement despite the agency’s utter failure over five years to ensure that there was enough RRC space. But as Dostoevsky or Tolstoy (or both) figured out, just because you can force yourself to not think about it doesn’t mean it isn’t there.