We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

PAY YOUR MONEY AND TAKE YOUR CHANCE

I had a contracts professor in law school a half-century ago who would every so often wave his arm expansively in the general direction of the library and remind us, “Remember, there’s enough law in there for everyone.”

Fifty years later, I get his point.

Fifty years later, I get his point.

This week, two federal courts of appeal found enough law to let them answer the same question in opposite ways.

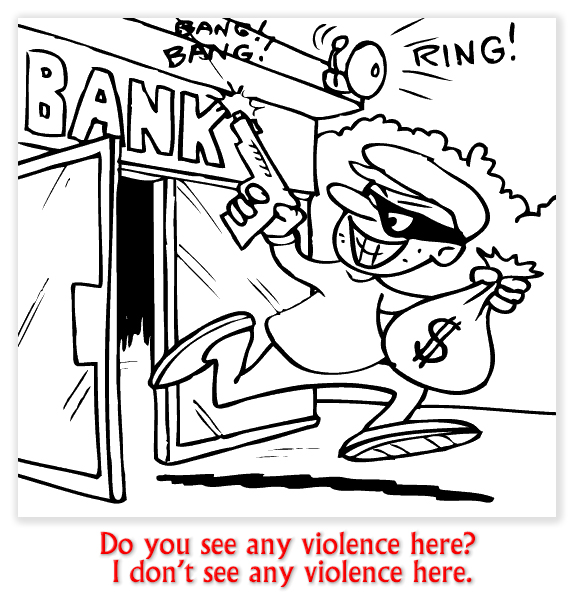

For a criminal statute to constitute a crime of violence that will support a conviction under 18 USC § 924(c) – possessing or using a gun during a crime of violence or drug offense – an offender must be unable to commit the crime without attempting or using or threatening to use physical force. Kidnapping? Sounds violent as hell, but one can kidnap someone by walking out of a room they’re in and locking the door so they cannot get out. You and your friends can plan to shoot the CEO of the Wesayso Corporation for poisoning society with low-quality honeybuns, but conspiring to murder someone is not a crime of violence, because you can conspire without using physical force.

Here’s the rub. In order to avoid the crime of violence label, the crime cannot be divisible. The statute must express the alternatives as “means” and not “elements.” If in a statute such as the bank robbery statute (18 USC § 2113), Congress created two separate criminal offenses —one violent (done by force or threat of force) and the other not—the statute is divisible. Then, the part of the statute that defines a violent crime will support the § 924(c) conviction. But if the statute is indivisible and merely sets forth three alternative means—such as force, threat of force, and extortion—of completing the same crime, then if extortion can be done without violence, the statute will not support a § 924(c) conviction, no matter how weird it might seem that a law prohibiting armed bank robbery cannot support a mandatory gun penalty statute like 18 USC § 924(c).

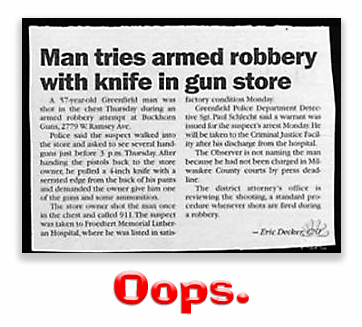

Bryan Burwell and Aaron Perkins have spent the last 23 years or so in prison for their bit parts in a string of armed bank robberies. Unfortunately, the ringleaders armed themselves with fully automatic AK-47s, which led to 18 USC § 924(c) consecutive sentences of 30 years apiece.

Bryan Burwell and Aaron Perkins have spent the last 23 years or so in prison for their bit parts in a string of armed bank robberies. Unfortunately, the ringleaders armed themselves with fully automatic AK-47s, which led to 18 USC § 924(c) consecutive sentences of 30 years apiece.

Even more unfortunately, the ringleaders had the foresight to make deals to testify against Bryan and Aaron. The ringleaders had their § 924(c) counts dropped and are out of prison. Bryan and Aaron have another 15 years to go.

On Monday, the D.C. Circuit ruled that the federal bank robbery statute is not divisible. It prohibits bank robbery committed by use of force, threat of force, attempted use of force or extortion. Because extortion is committed not only by threatening someone with future violence but with the future accusation of a crime, an embarrassing revelation or loathsome disease, a bank robbery could conceivably be accomplished by threatening to tell the branch manager’s wife that he was having an affair if he didn’t empty the vault into your duffel bag.

The Circuit concluded that the statute, which criminalizes bank robbery completed “by force and violence, or by intimidation,” or “by extortion” is not divisible. Because of that, a § 2113(a) bank robbery cannot support a § 924(c) conviction:

Force and violence, intimidation, and extortion are three ways a person might rob a bank. The text and structure of the statute indicate that extortion is a factual means of bank robbery, rather than an element of an entirely separate offense. That conclusion is reinforced by the statutory history and common law roots of robbery and extortion. As an indivisible offense, bank robbery is not a § 924(c) crime of violence

As a result, Bryan and Aaron will walk free after over 20 years in prison.

Not so John Armstrong, convicted in Florida of § 2113(a) bank robbery and multiple § 924(c) offenses. Like Bryan and Aaron, John argued that § 2113(a) cannot be a crime of violence because it can be committed through use of extortion. Two days after the D.C. Circuit said extortion and force were just means of violating § 2113(a), the 11th Circuit said they were really elements, meaning that § 2113(a) describes two divisible crime, robbery by force and robbery by extortion.

Not so John Armstrong, convicted in Florida of § 2113(a) bank robbery and multiple § 924(c) offenses. Like Bryan and Aaron, John argued that § 2113(a) cannot be a crime of violence because it can be committed through use of extortion. Two days after the D.C. Circuit said extortion and force were just means of violating § 2113(a), the 11th Circuit said they were really elements, meaning that § 2113(a) describes two divisible crime, robbery by force and robbery by extortion.

John was convicted of aiding and abetting a robbery by force, and thus must continue serving his 35-year sentence (resulting from multiple § 924(c) counts).

Agreeing with a prior 1st Circuit decision, the 11th held that “the fact that the language ‘or obtains or attempts to obtain’ immediately precedes the phrase ‘by extortion’ (as opposed to ‘takes, or attempts to take,’ which relates to the ‘by force or violence’ and ‘intimidation’)… suggests that extortion is not an alternative means of commission. We agree that a plain reading of the text supports the conclusion that robbery and extortion are alternate elements—amounting to separate crimes—not alternate means of committing one crime.”

The 11th ruled that § 2113(a)’s distinction between ‘taking’ and ‘obtaining’ “reflects the fundamental division between robbery and extortion, namely, that robbery involves taking possession of the property of another against his will while extortion involves taking possession of the property of another with consent—albeit grudging or coerced.”

Circuit splits – where two federal appellate courts reach diametrically opposed conclusions – happen regularly enough. Such matters are routinely settled by the Supreme Court, as this one surely will be. However, rarely do the conflicting decisions get handed down within 48 hours.

Circuit splits – where two federal appellate courts reach diametrically opposed conclusions – happen regularly enough. Such matters are routinely settled by the Supreme Court, as this one surely will be. However, rarely do the conflicting decisions get handed down within 48 hours.

Count on this one to be settled by SCOTUS. Meanwhile, Bryan and Aaron will have Christmas at home, John will not – all due to there being enough law out there for two Circuits to answer the same legal question in two irreconcilable ways in the same week.

United States v. Burwell, Case Nos. 16-3009 (D.C. Cir. Dec. 9, 2024), 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 31086

United States v. Armstrong, Case No. 21-11252 (11th Cir. Dec. 11, 2024), 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 31549

– Thomas L. Root

A conviction for using a gun in a crime of violence under 18 USC § 924(c) requires that the underlying offense being committed while using the gun be a felony involving the “use of physical force” against another person. Shooting someone obviously qualifies, but what if the underlying crime can be committed by doing nothing? Doing nothing hardly involves the “use of physical force” against another person.

A conviction for using a gun in a crime of violence under 18 USC § 924(c) requires that the underlying offense being committed while using the gun be a felony involving the “use of physical force” against another person. Shooting someone obviously qualifies, but what if the underlying crime can be committed by doing nothing? Doing nothing hardly involves the “use of physical force” against another person. SCOTUS held that it was a crime of violence. The high court ruled that while Sal argued that an offender can commit 2nd-degree murder without being the actual cause of the victim’s death because the offender can do so through “omission of a legal duty. But the test for ‘actual causality’ is whether the victim’s death ‘would not have occurred in the absence of—that is, but for—the defendant’s conduct…’ When a child starves to death after the parents refuse to provide food, the parents’ conduct is no less a cause of death than if the parents had poisoned the child.”

SCOTUS held that it was a crime of violence. The high court ruled that while Sal argued that an offender can commit 2nd-degree murder without being the actual cause of the victim’s death because the offender can do so through “omission of a legal duty. But the test for ‘actual causality’ is whether the victim’s death ‘would not have occurred in the absence of—that is, but for—the defendant’s conduct…’ When a child starves to death after the parents refuse to provide food, the parents’ conduct is no less a cause of death than if the parents had poisoned the child.” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a spirited dissent, in which Justice Ketanji Jackson joined, but the decision suggests that SCOTUS is finding some practical limits to its “crime of violence” jurisprudence. After all, if doing nothing is physical force, there seem to be no practical limits on what might be a crime of violence.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a spirited dissent, in which Justice Ketanji Jackson joined, but the decision suggests that SCOTUS is finding some practical limits to its “crime of violence” jurisprudence. After all, if doing nothing is physical force, there seem to be no practical limits on what might be a crime of violence.