We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SUPREME COURT HOLDS 59(e) MOTION IS NOT A SECOND BITE OF THE HABEAS APPLE

For the last 2 years, prisoners seeking one final whack at the lawfulness of their convictions or sentences have had to contend with the limitations of a law known by the mouthful “Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996.”

Even the name of the Act is strange. No one can be opposed to “antiterrorism.” Well, almost no one. But “effective death penalty?” I suppose an effective death penalty is one that leaves you dead. But what Congress was getting at here was a means of limiting what some lawmakers thought were endless habeas corpus actions brought by the condemned, so that their date with the Grim Reaper could be delayed as long as possible. The AEDPA was intended to limit such collateral attacks, so that execution was more likely to kill the prisoner than old age.

Even the name of the Act is strange. No one can be opposed to “antiterrorism.” Well, almost no one. But “effective death penalty?” I suppose an effective death penalty is one that leaves you dead. But what Congress was getting at here was a means of limiting what some lawmakers thought were endless habeas corpus actions brought by the condemned, so that their date with the Grim Reaper could be delayed as long as possible. The AEDPA was intended to limit such collateral attacks, so that execution was more likely to kill the prisoner than old age.

But the practical effect of the AEDPA was to severely limit the right of prisoners to the federal writ of habeas corpus. The Act set hard time limits on filing motions under 28 USC 2254 (for state prisoners seeking federal habeas relief) and 28 USC 2255 (for federal prisoners), and – important for today’s topic – the right to bring a second 2254/2255 motion after the first one has been decided.

There was a time when a prisoner could file as many 2254 or 2255 motions (known as “second-or-successive” motions) as a court would accept before concluding that the prisoner was “abusing the writ.” But the AEDPA turned the equitable and flexible “abuse of the writ” doctrine into a rigid statutory rule. Now, a prisoner seeking to file a second-or-successive 2255 motion must first get permission to do so from the court of appeals, and the circumstances under which permission can be granted are tightly circumscribed by 28 USC 2244.

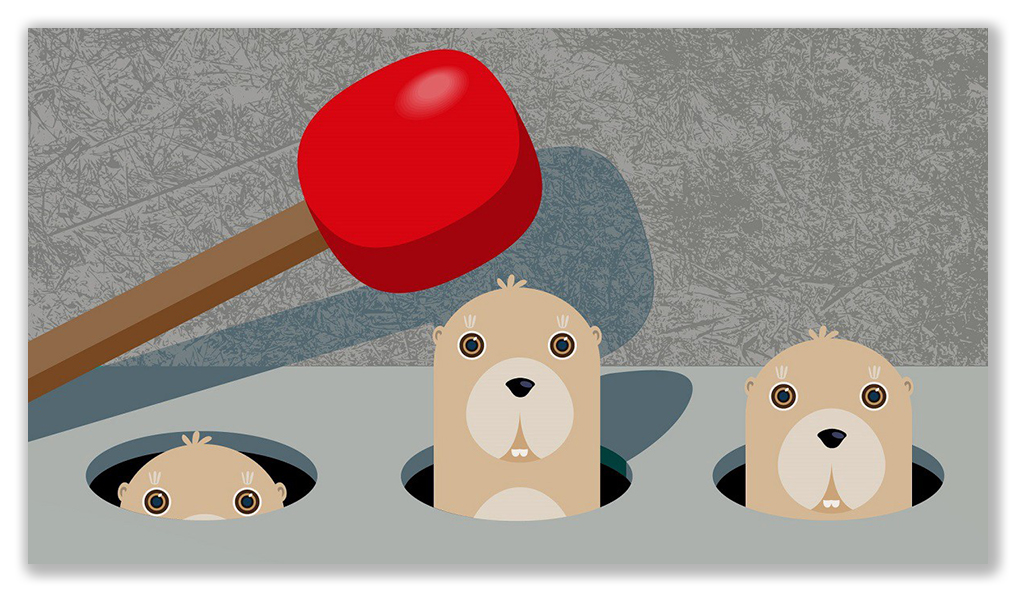

But water seeks and finds its own level, and in the wake of the AEDPA’s passage, crafty prisoners filed all manner of other motions instead of second-or-successive 2255s. They would file petitions for writs of mandamus or error coram nobis or audita querela, or Rule 60(b) motions, or civil actions. The courts would whack down the efforts as fast as the prisoners filed them, holding that a motion by any other name was in effect a second-or-successive 2255 if it attacked the conviction or sentence in some manner.

In civil procedure, a motion brought under Federal Rule Civil Procedure 60(b) asks a court to set aside a judgment that is already final, based on any of a variety of reasons (the favorite one probably being due to newly-discovered evidence). Rule 60(b) quickly became an inmate favorite, letting the movant try to reopen a former 2255 proceeding well after the fact because of evidence of some new constitutional violation or even just more evidence on an issue already raised and lost. In 2005, the Supreme Court ruled in Gonzalez v. Crosby that such a motion was really a second-and-successive 2255 prohibited by the AEDPA unless the motion was solely addressed to some infirmity in the 2255 proceeding itself.

In civil procedure, a motion brought under Federal Rule Civil Procedure 60(b) asks a court to set aside a judgment that is already final, based on any of a variety of reasons (the favorite one probably being due to newly-discovered evidence). Rule 60(b) quickly became an inmate favorite, letting the movant try to reopen a former 2255 proceeding well after the fact because of evidence of some new constitutional violation or even just more evidence on an issue already raised and lost. In 2005, the Supreme Court ruled in Gonzalez v. Crosby that such a motion was really a second-and-successive 2255 prohibited by the AEDPA unless the motion was solely addressed to some infirmity in the 2255 proceeding itself.

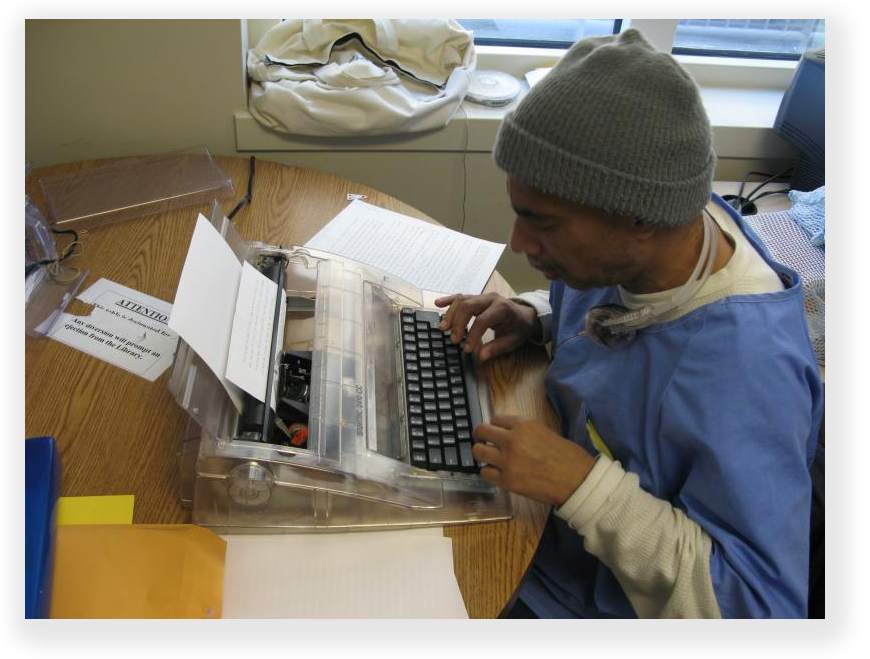

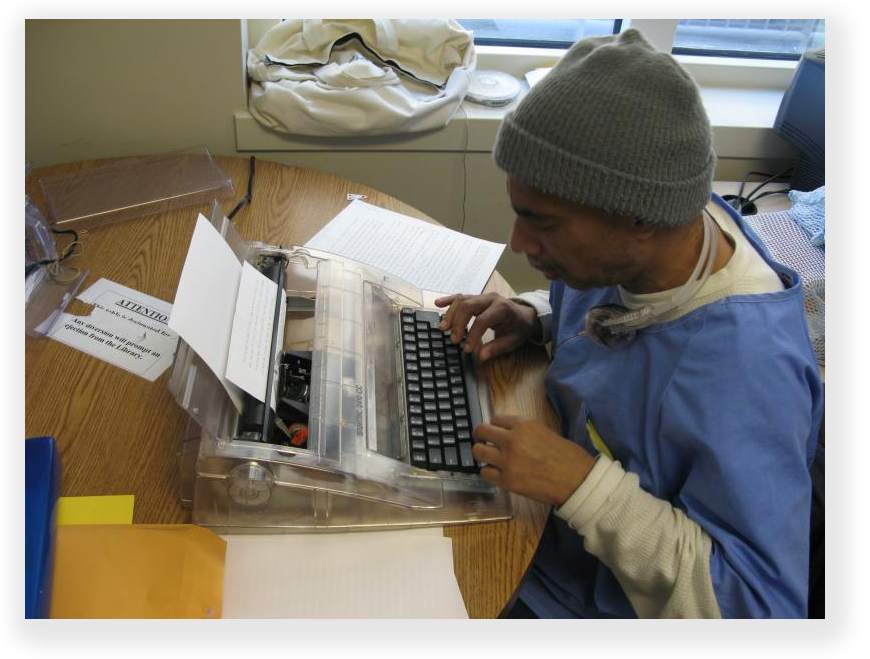

Fast forward 15 years to yesterday. Texas prisoner Greg Banister lost his 28 USC 2254 proceeding, in which he challenged his state conviction in federal court after losing in all of the Texas courts. He lost in front of the federal district judge, too, but – having access to both a book of federal civil rules and a typewriter – Greg promptly filed a motion to alter or amend the judgment under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 59(e). Rule 59(e) gives a party one more chance to convince the district court it was wrong in its judgment, and it stops a judgment from becoming final as long as it was filed on time and remains pending.

The federal judge, not any more impressed by Greg’s Rule 59(e) motion than it had been by the underlying 2254 petition, denied the motion. Greg then filed his notice of appeal. However, the district court ruled that the Rule 59(e) motion had really been a second-or-successive 2254 motion over which the court had no jurisdiction. Therefore, the court said, the Rule 59(e) motion had not kept the court’s judgment from becoming final the day it was entered, and that meant that Greg’s notice of appeal – which would have been timely if Greg’s Rule 59(e) filing had stayed finality of the judgment – was late.

The Fifth Circuit agreed with the trial judge. Thus, Greg was denied his appeal.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court reversed the decision. Justice Kagan, writing for a 7-2 court, observed that the case “is about two procedural rules. First, Rule 59(e) applies in federal civil litigation generally. (Habeas proceedings, for those new to the area, are civil in nature)… The Rule enables a party to request that a district court reconsider a just-issued judgment. Second, the so-called gatekeeping provision of the… AEDPA, codified at 28 USC §2244(b), governs federal habeas proceedings. It sets stringent limits on second or successive habeas applications.”

The Supreme Court observed that even under the old “abuse of the writ” standard, courts had historically considered Rule 59(e) motions filed in habeas corpus cases on their merits. Plus, a prisoner may invoke Rule 59(e) only to request “reconsideration of matters properly encompassed” in the challenged judgment. And, the Court said, “’reconsideration’ means just that: Courts will not entertain arguments that could have been but were not raised before the just-issued decision. A Rule 59(e) motion is therefore backward-looking; and because that is so, it maintains a prisoner’s incentives to consolidate all of his claims in his initial application.”

The Supreme Court observed that even under the old “abuse of the writ” standard, courts had historically considered Rule 59(e) motions filed in habeas corpus cases on their merits. Plus, a prisoner may invoke Rule 59(e) only to request “reconsideration of matters properly encompassed” in the challenged judgment. And, the Court said, “’reconsideration’ means just that: Courts will not entertain arguments that could have been but were not raised before the just-issued decision. A Rule 59(e) motion is therefore backward-looking; and because that is so, it maintains a prisoner’s incentives to consolidate all of his claims in his initial application.”

As well, the Rule consolidates appellate proceedings. “A Rule 59(e) motion briefly suspends finality to enable a district court to fix any mistakes and thereby perfect its judgment before a possible appeal,” Justice Kagan wrote. “The motion’s disposition then merges into the final judgment that the prisoner may take to the next level. In that way, the Rule avoids ‘piecemeal appellate review’… Its operation, rather than allowing re-peated attacks on a decision, helps produce a single final judgment for appeal.”

The Court contrasting the speed and efficiency of a Rule 59(e) motion with a Rule 60(b) motion, which can be filed years after the judgment. The availability of a Rule 60(b) motion “threatens serial habeas litigation; indeed, without rules suppressing abuse, a prisoner could bring such a motion endlessly. By contrast, a Rule 59(e) motion is a one-time effort to bring alleged errors in a just-issued decision to a habeas court’s attention, before taking a single appeal. It is a limited continuation of the original proceeding—indeed, a part of producing the final judgment granting or denying habeas relief. For those reasons, Gonzalez does not govern here.”

Banister v. Davis, Case No. 18–6943, 2020 U.S. LEXIS 3037 (Supreme Court, June 1, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

Generally (a word that is employed dangerously where the law is concerned), every federal prisoner is entitled to file one post-conviction habeas corpus motion challenging his or her conviction under 28 USC § 2255. To file a second one – called a “second-or-successive” 2255 – a prisoner must first petition the court of appeals having jurisdiction over his or her district court for permission to do so.

Generally (a word that is employed dangerously where the law is concerned), every federal prisoner is entitled to file one post-conviction habeas corpus motion challenging his or her conviction under 28 USC § 2255. To file a second one – called a “second-or-successive” 2255 – a prisoner must first petition the court of appeals having jurisdiction over his or her district court for permission to do so. In 2007, Ronald Jones was convicted of meth distribution. It was not Ron’s first rodeo – he had two California drug distribution priors. Under 21 USC § 841(b)(1)(A), a defendant with two prior drug convictions would see his or her mandatory minimum set at 300 months. Ron got 360 months.

In 2007, Ronald Jones was convicted of meth distribution. It was not Ron’s first rodeo – he had two California drug distribution priors. Under 21 USC § 841(b)(1)(A), a defendant with two prior drug convictions would see his or her mandatory minimum set at 300 months. Ron got 360 months. Not every Circuit agrees with the 6th on this. So far, only the 4th, 7th, 10th and 11th concur that petitions like Ron’s are not successive. The decision could set up a Supreme Court review, but the government would have to be the one to appeal, and that’s unlikely.

Not every Circuit agrees with the 6th on this. So far, only the 4th, 7th, 10th and 11th concur that petitions like Ron’s are not successive. The decision could set up a Supreme Court review, but the government would have to be the one to appeal, and that’s unlikely.