We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE 10TH GIVETH, THE 10TH TAKETH AWAY

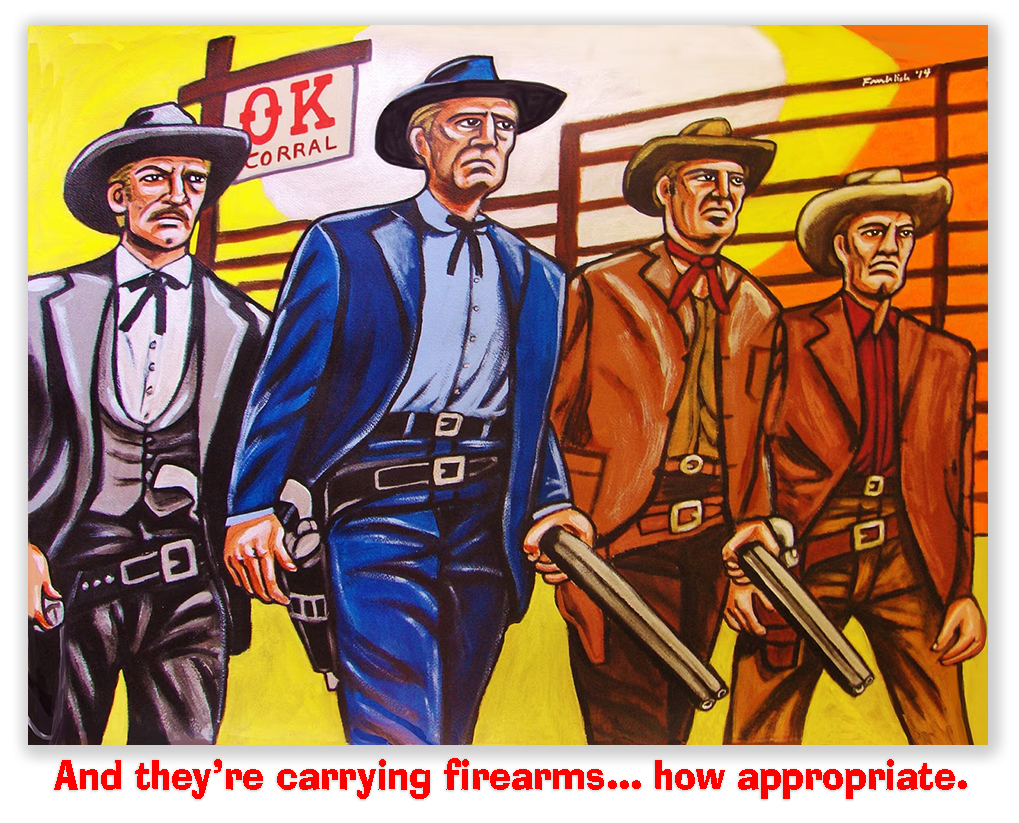

In the world of gun restrictions, all eyes are on the Supreme Court, which will decide United States v. Rahimi – and maybe the future of the 2nd Amendment – sometime between now and June. But litigation over 18 USC § 922(g), the laundry list of people who the government says should not have guns or ammo, in the lower courts continues unabated.

In the world of gun restrictions, all eyes are on the Supreme Court, which will decide United States v. Rahimi – and maybe the future of the 2nd Amendment – sometime between now and June. But litigation over 18 USC § 922(g), the laundry list of people who the government says should not have guns or ammo, in the lower courts continues unabated.

Out in the wild, wild west, the 10th Circuit last week handed down a pair of 18 USC § 922(g) decisions, giving defendants a mixed bag.

In one case, Colorado defendant Kenneth Devereaux was convicted of being a felon in possession of a gun (violation of 18 USC § 922(g)(1)). He received a 2-level enhancement in his Guidelines range because the district judge considered a prior conviction for assault under 18 USC § 113(a)(6) to be a crime of violence.

Last week, the 10th Circuit disagreed. A “§ 113(a)(6) assault can be committed recklessly,” the Circuit observed, but since the 2021 Supreme Court decision in Borden v. United States, “a reckless offense categorically does not have as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another.”

Last week, the 10th Circuit disagreed. A “§ 113(a)(6) assault can be committed recklessly,” the Circuit observed, but since the 2021 Supreme Court decision in Borden v. United States, “a reckless offense categorically does not have as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another.”

Section 113(a)(6) “sets forth a single indivisible assault offense, to which only the categorical… approach [applies],” the 10th ruled. “Because an assault resulting in serious bodily injury under § 113(a)(6) can be committed recklessly, after Borden it cannot qualify as a crime of violence…”

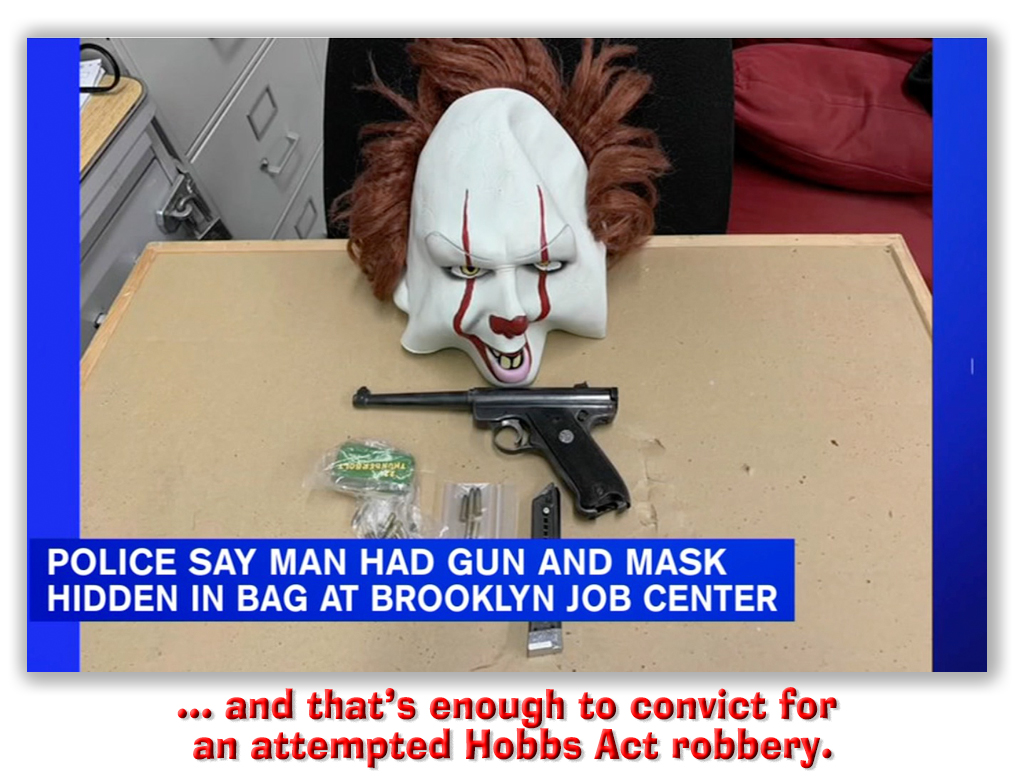

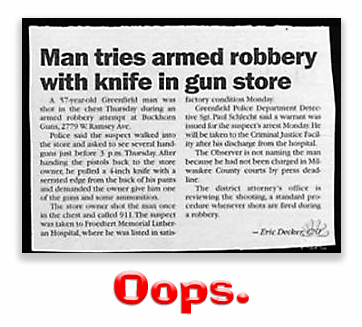

Things did not go so well for Jonathan Morales-Lopez. He and a buddy were caught stealing guns from a Utah gun store. When he was frisked, the police found a loaded Smith and Wesson he had previously stolen from the same store stuffed in his pants and a personal-use amount of meth in a plastic bag.

The State of Utah did its number on Jonathan for the theft, but the Feds picked up the gun case. He was charged as an unlawful drug user in possession of a gun under 18 USC § 922(g)(3). After he was convicted, Jon argued that § 922(g)(3) was unconstitutionally vague, violating his 5th Amendment rights. The district court agreed with Jon, and the government appealed.

“When the validity of a statute is drawn in question, and even if a serious doubt of constitutionality is raised,” the Circuit wrote, “it is a cardinal principle that courts]will first ascertain whether a construction of the statute is fairly possible by which the question may be avoided.” To avoid the vagueness problem, the 10th said, courts have interpreted § 922(g)(3) to convict a defendant only if the Government “introduced sufficient evidence of a temporal nexus between the drug use and firearm possession.”

Here, the appeals court said, that wasn’t even a close call. Jon was carrying his personal meth stash in his pocket and told the police after his arrest that he couldn’t remember much because he was high on the controlled substance at the time. “The facts presented at trial, coupled with reasonable inferences drawn from those facts, could support the conclusion that Morales-Lopez was an “unlawful user” of methamphetamine,” the Circuit held, “one whose use was ‘regular and ongoing, while in possession of a stolen firearm.”

Here, the appeals court said, that wasn’t even a close call. Jon was carrying his personal meth stash in his pocket and told the police after his arrest that he couldn’t remember much because he was high on the controlled substance at the time. “The facts presented at trial, coupled with reasonable inferences drawn from those facts, could support the conclusion that Morales-Lopez was an “unlawful user” of methamphetamine,” the Circuit held, “one whose use was ‘regular and ongoing, while in possession of a stolen firearm.”

What is puzzling is that Jon’s lawyer did not argue that § 922(g)(3) violated the 2nd Amendment, a claim that has already gotten traction in at least one other court of appeal. Hunter Biden plans that defense. Jon’s lawyer’s failure to raise it may be a subject for his § 2255 motion.

United States v. Devereaux, Case No. 22-1203, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 2751 (10th Cir., February 6, 2024)

Borden v. United States, 141 S. Ct. 1817, 210 L. Ed. 2d 63 (Supreme Court, 2021)

United States v. Morales-Lopez, Case No. 22-4074, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 3051 (10th Cir., February 9, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root