We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

I THINK, THEREFORE I AM…

Watch me write an entire post without ever using the words “coronavirus” or “COVID-19.”

Despite our fixation-in-place with the pandemic, some legal news beyond The CARES Act release to home confinement of Michael Cohen is still being made.

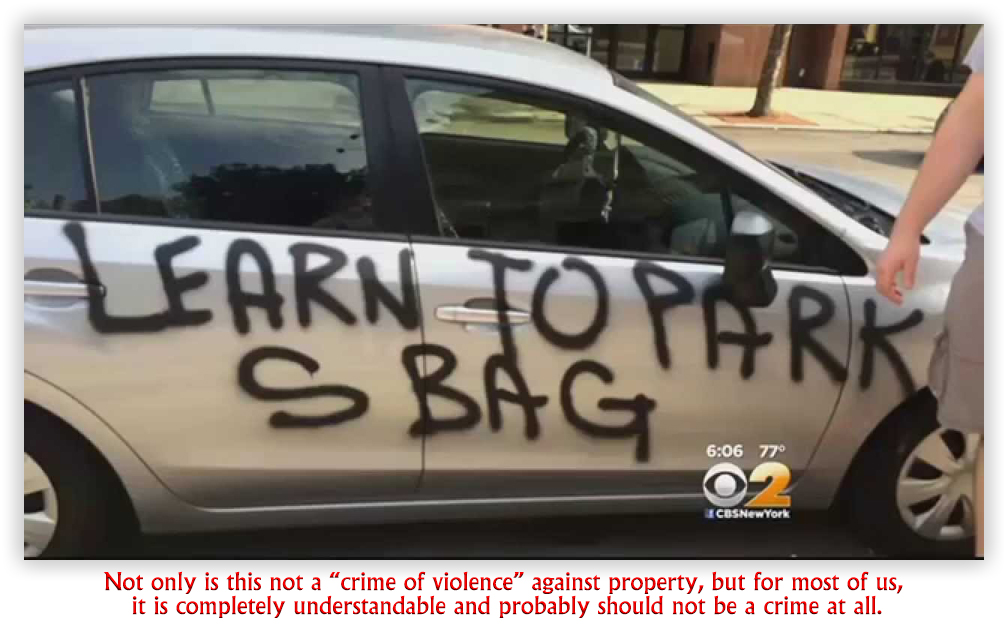

A 9th Circuit decision last week held that even after the Supreme Court’s United States v. Davis decision last summer, a Hobbs Act armed robbery remains a crime of violence for purposes of 18 USC 924(c)(3)(A). That’s unsurprising: other than the pending 9th Circuit case United States v. Chea, there is hardly a groundswell to declare robberies to be non-violent.

A 9th Circuit decision last week held that even after the Supreme Court’s United States v. Davis decision last summer, a Hobbs Act armed robbery remains a crime of violence for purposes of 18 USC 924(c)(3)(A). That’s unsurprising: other than the pending 9th Circuit case United States v. Chea, there is hardly a groundswell to declare robberies to be non-violent.

But the 9th went beyond that and held, in a 2-1 decision, that – where a substantive offense is a crime of violence under 18 USC § 924(c)(3)(A) – an attempt to commit that offense is also a crime of violence.

The defendant, who had previously pulled off an armored car heist for a $900,000 score, decided to reprise his success. Unfortunately for him, the FBI had offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to his arrest, a pot of legit money that was enough to convince his sidekick to rat him out.

As the defendant drove toward the armored car garage, he got spooked by too much law enforcement activity in the area, and decided to abort. He was arrested a few days later, and convicted of attempted Hobbs Act robbery and carrying a gun during a crime of violence under 18 USC § 924(c).

The Circuit upheld the conviction, holding:

We agree with the Eleventh Circuit that attempted Hobbs Act armed robbery is a crime of violence for purposes of § 924(c) because its commission requires proof of both the specific intent to complete a crime of violence, and a substantial step actually (not theoretically) taken toward its completion… It does not matter that the substantial step—be it donning gloves and a mask before walking into a bank with a gun, or buying legal chemicals with which to make a bomb — is not itself a violent act or even a crime. What matters is that the defendant specifically intended to commit a crime of violence and took a substantial step toward committing it. The definition of “crime of violence” in § 924(c)(3)(A) explicitly includes not just completed crimes, but those felonies that have the “attempted use” of physical force as an element. It is impossible to commit attempted Hobbs Act robbery without specifically intending to commit every element of the completed crime, which includes the commission or threat of physical violence. 18 U.S.C. § 1951. Since Hobbs Act robbery is a crime of violence, it follows that the attempt to commit Hobbs Act robbery is a crime of violence.

Judge Nguyen dissented, succinctly observing that “as the majority acknowledges, an attempted Hobbs Act robbery can be committed without any actual use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force. Therefore, it plainly does not fit the definition of a crime of violence under the elements clause. Yet in a leap of logic, the majority nevertheless holds that “when a substantive offense is a crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(3)(A), an attempt to commit that offense is also a crime of violence.”

Several district courts in the Second Circuit have held that attempted Hobbs Act robberies are not crimes of violence. I suspect this question will ultimately be settled at the Supreme Court.

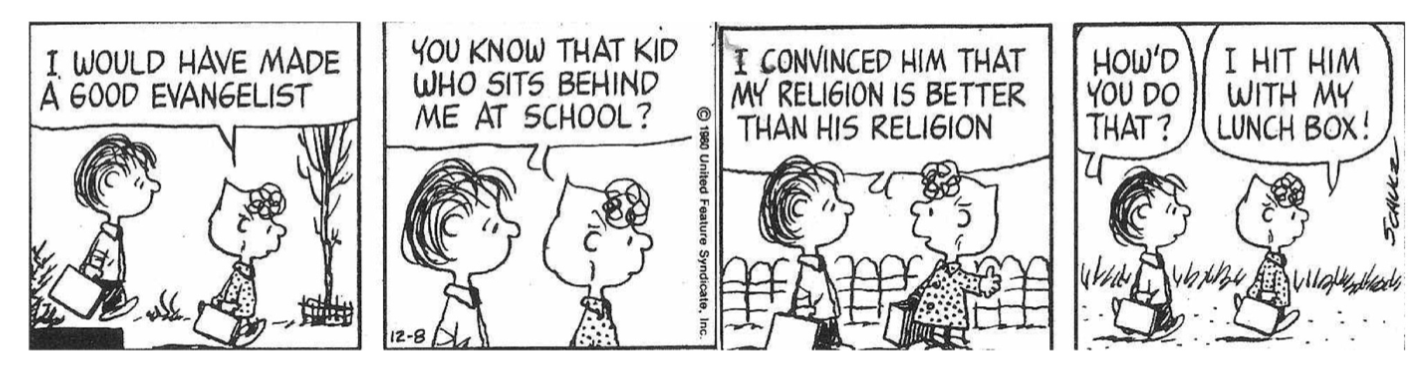

French philosopher René Descartes famously posited, “Cogito, ergo sum.” For those of you who did not have Emily Bernges for high school Latin, this translates as, “I think, therefore I am.”

French philosopher René Descartes famously posited, “Cogito, ergo sum.” For those of you who did not have Emily Bernges for high school Latin, this translates as, “I think, therefore I am.”

The 9th Circuit’s corollary is “I think about violence, therefore I have committed violence.” Somehow, it doesn’t have the same ring to it.

United States v. Dominguez, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 10863 (9th Cir., April 7, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root