We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

USSC SETS GUIDELINE AMENDMENT PRIORITIES

The U.S. Sentencing Commission held its first meeting in 46 months last Friday, voting in a 20-minute session to adopt priorities for the Guidelines amendment cycle that ends Nov 1, 2023.

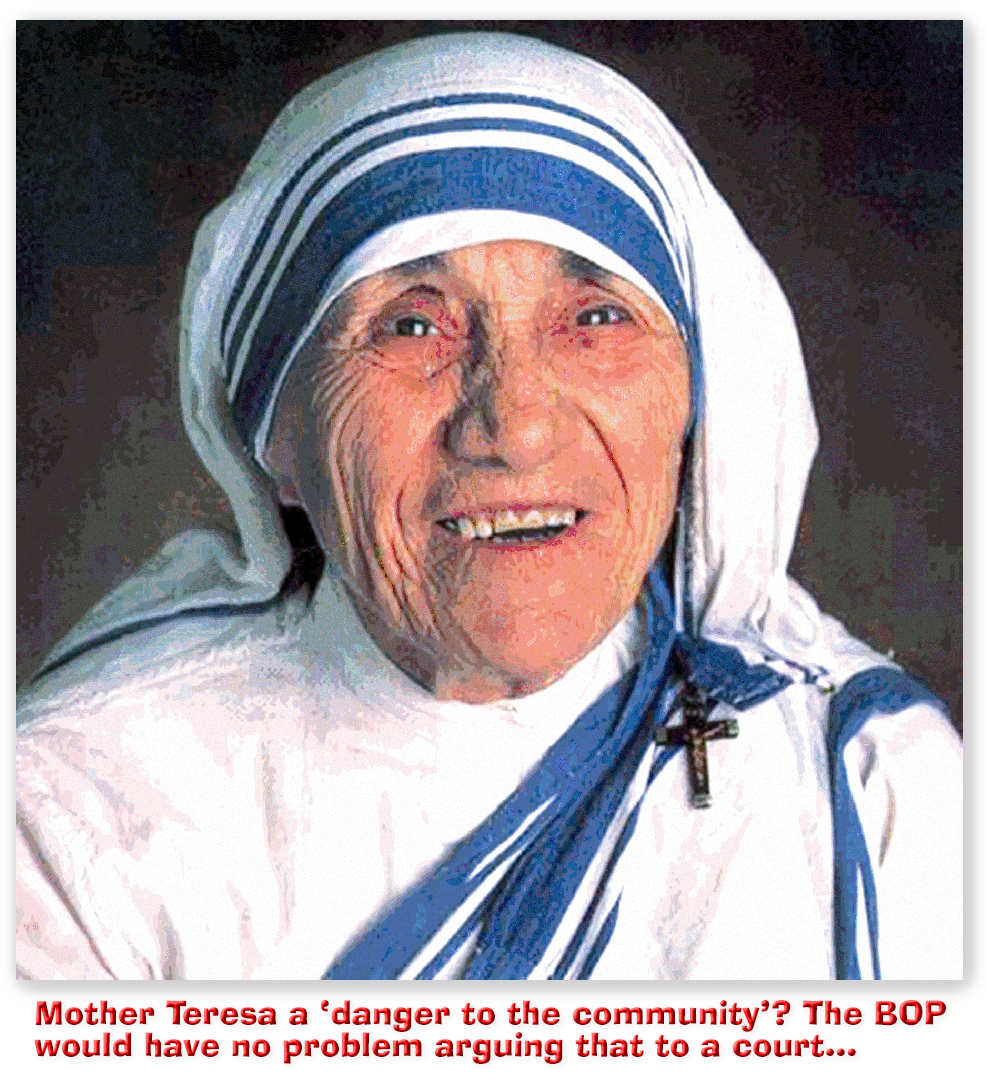

The USSC lost its quorum due to term expirations of multiple members in December 2018, just as the First Step Act was signed into law. That meant the commission was unable to revise the Guidelines just as First Step changes required modifications that would have prevented conflicting judicial interpretations, especially in the application of 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) sentence reduction motions, commonly called “compassionate release” motions.

The USSC lost its quorum due to term expirations of multiple members in December 2018, just as the First Step Act was signed into law. That meant the commission was unable to revise the Guidelines just as First Step changes required modifications that would have prevented conflicting judicial interpretations, especially in the application of 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A) sentence reduction motions, commonly called “compassionate release” motions.

The compassionate release statute requires judges to consult USSG § 1B1.13, Guidelines policy on granting compassionate releases, but § 1B1.13 was written for a time when only the Bureau of Prisons could bring compassionate release motions. Most but not all Circuits have ruled that § 1B1.13 is not binding on district courts until it is amended, but the 11th has ruled that it is binding, the 8th has studiously avoided deciding the question, and others – such as the 3rd, 6th and 7th – have held that district judges cannot consider First Step Act changes in sentencing law that would result in much lower sentences when deciding compassionate release motions.

U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves (S.D. Mississippi), chairman of the Commission, said implementing the First Step Act through revisions to the federal sentencing guidelines would be the USSC’s “top focus.”

Other changes in the Guidelines, such as to the drug tables, could result from First Step’s lowering of drug mandatory minimums.

Additional priorities for the coming year include resolving circuit conflicts over whether the government may withhold a motion for a third acceptance-of-responsibility point just because a defendant moved to suppress evidence before pleading guilty and whether an offense must involve a substance actually controlled by the Controlled Substances Act to qualify as a “controlled substance offense,”

Additional priorities for the coming year include resolving circuit conflicts over whether the government may withhold a motion for a third acceptance-of-responsibility point just because a defendant moved to suppress evidence before pleading guilty and whether an offense must involve a substance actually controlled by the Controlled Substances Act to qualify as a “controlled substance offense,”

The USSC will also consider amendments to the Guidelines career offender chapter that would provide an alternative to the “categorical approach” in determining whether an offense is a “crime of violence” or a “controlled substance offense.

First Step also made changes to the “safety valve,” which relieves certain drug trafficking offenders from statutory mandatory minimum penalties, by expanding eligibility to some defendants with more than one criminal history point. A USSC press release says the Commission “intends to issue amendments to § 5C1.2 to recognize the revised statutory criteria and consider changes to the 2-level reduction in the drug trafficking guideline currently tied to the statutory safety valve.”

The only addition to the Commission’s previously-published list of proposed priorities that came out of the meeting was consideration of possible amendments on whether, and to what extent, people’s criminal history for marijuana possession can be used against them in sentencing.

The only addition to the Commission’s previously-published list of proposed priorities that came out of the meeting was consideration of possible amendments on whether, and to what extent, people’s criminal history for marijuana possession can be used against them in sentencing.

The cannabis item was added and adopted after President Joe Biden issued a mass marijuana pardon proclamation.

The Commission’s priorities only guide what it will be working on for the Nov 2023 amendment cycle. Expect amendment proposals by late January, followed by a public comment period, and final amendments by May 1. After that, the Senate has 6 months to reject any of the amendments (a very rare occurrence). Amendments not rejected will become effective Nov 1, 2023.

Reuters, Newly-reconstituted U.S. sentencing panel finalizes reform priorities (October 28, 2022)

US Sentencing Commission, Final Priorities for Amendment Cycle (October 5, 2022)

US Sentencing Commission, Commission Sets Policy Priorities (October 28, 2022)

Marijuana Moment, Federal Commission Considers Changes To How Past Marijuana Convictions Can Affect Sentencing For New Crimes (October 28, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root