We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

IS § 924(c) A VIOLENT CRIME?

I still get questions from people asking whether 18 U.S.C. § 924(c) remains a “crime of violence.”

The answer is that § 924(c) – which criminalizes the use of a gun during a crime of violence or drug trafficking offense – has never itself been a “crime of violence.”

“C’mon, man!” I hear people out in TV Land saying, “how can using a gun in a crime not be a “crime of violence?”

“C’mon, man!” I hear people out in TV Land saying, “how can using a gun in a crime not be a “crime of violence?”

To you I say, “Welcome to federal criminal law.”

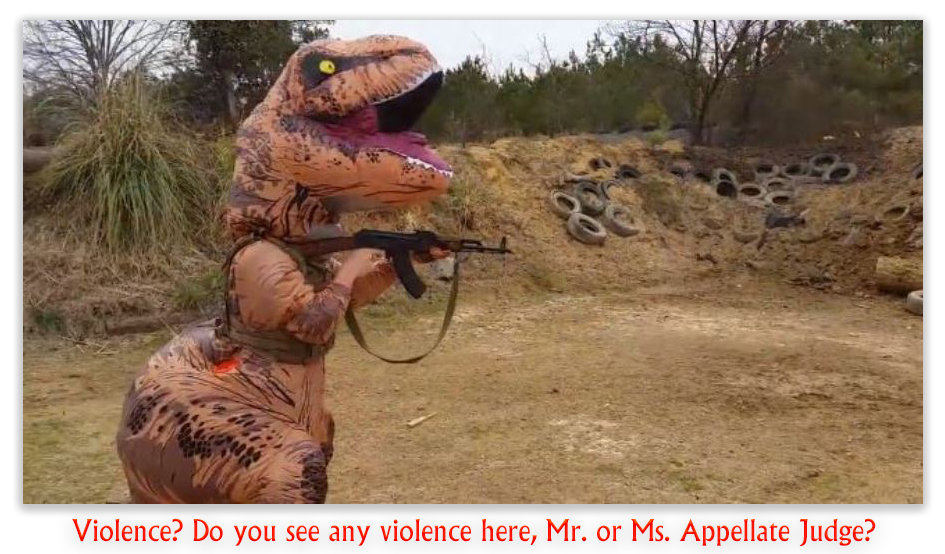

To those prisoners with § 924(c) charges because of an underlying drug offense, violence has nothing to do with nothing. The § 924(c) applies because you had a gun in the closet while you sold meth out of your bedroom. Or because you figured it’d be cool to have a Lorcin .380 stuck in your waistband where its principal threat was to your reproductive organs. You can’t have a gun while you’re selling controlled substances. It’s illegal. (Of course, selling controlled substances is illegal, too, but that’s a topic for another day).

To those people with § 924(c) charges because of an underlying crime of violence, the § 924(c) is not the “crime of violence.” It’s just a conviction resulting from another “crime of violence.”

Section 924(c) does define “crime of violence:” It’s (1) a felony; that is either

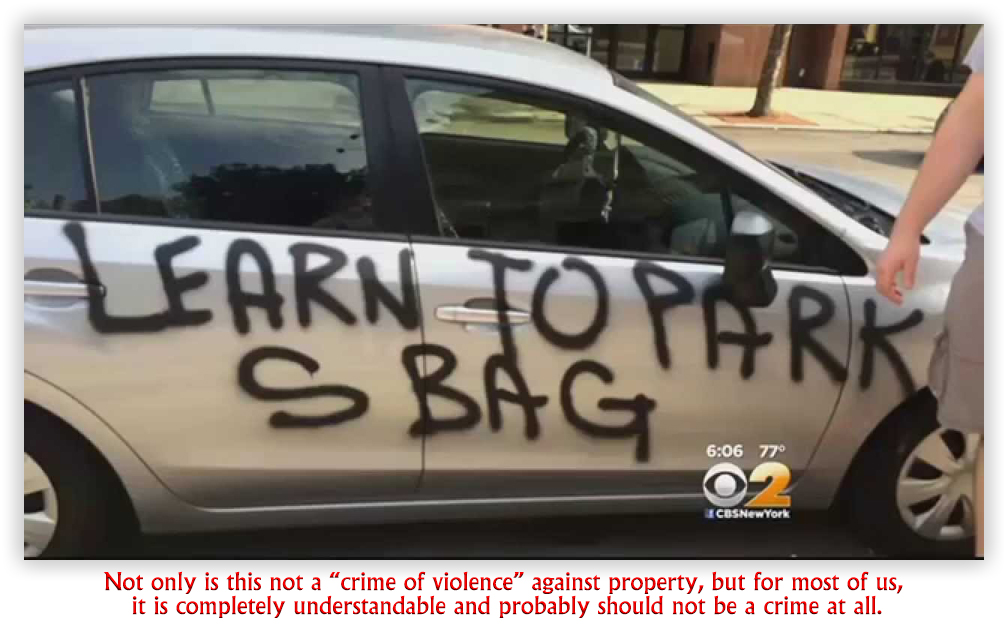

(A) has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another, or

(B) that by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in the course of committing the offense.

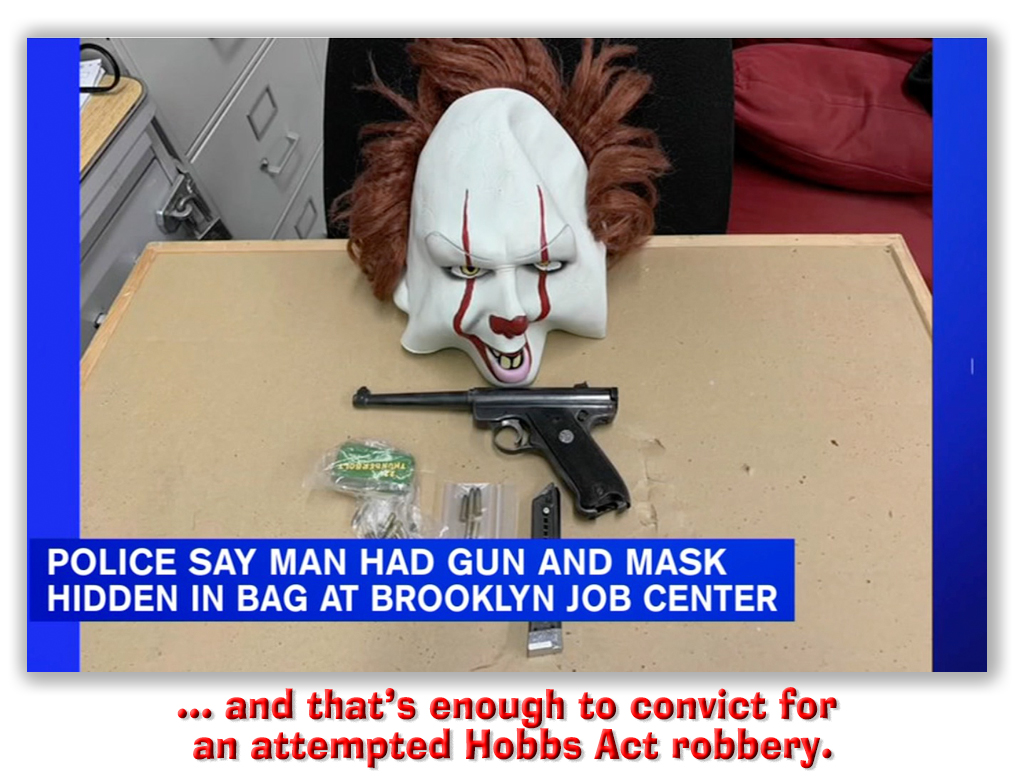

But after a line of Supreme Court decisions from Johnson v. United States through last year’s United States v. Taylor decision, alternate definition (b) has been invalidated as unconstitutionally vague. As a result, conspiracies to murder are not crimes of violence, because you can conspire with your buddies all night without using or threatening someone with the use of force. Attempts to rob a fellow drug dealer are not crimes of violence because you can complete an attempt just by walking up to the victim’s door with a gun in your hand and evil on your mind. In fact, some folks are starting to think that nothing is a “crime of violence” anymore.

But after a line of Supreme Court decisions from Johnson v. United States through last year’s United States v. Taylor decision, alternate definition (b) has been invalidated as unconstitutionally vague. As a result, conspiracies to murder are not crimes of violence, because you can conspire with your buddies all night without using or threatening someone with the use of force. Attempts to rob a fellow drug dealer are not crimes of violence because you can complete an attempt just by walking up to the victim’s door with a gun in your hand and evil on your mind. In fact, some folks are starting to think that nothing is a “crime of violence” anymore.

Under the circumstances, Tiffany Janis could be forgiven for thinking that her crime wasn’t violent, either. All she did was to come home, catch her cheatin’-heart husband in flagrante delicto, and express her displeasure by shooting him a few times.

Because the domestic discord played out on Indian reservation land, it ended up in federal court, where Tiffany was convicted of 2nd-degree murder and discharging a gun during and in relation to a crime of violence.

In a § 2255 motion, Tiffany argued that her 2nd-degree murder conviction was not a crime of violence, meaning that her § 924(c) conviction had to be vacated.

Tiffany’s murder conviction required that the government show she had killed another person “with malice aforethought.” She argued that killing a person “with malice aforethought” can be done without “us[ing] force against the person or property of another,” as required by § 924(c)(3)(A). Under SCOTUS’s Borden v. United States holding, Tiffany maintained, § 924(c)’s force clause requires “directing or targeting force” at another person or their property. The 8th’s 2nd-degree murder precedent, however, showed that “malice aforethought” can be established without a perp “targeting” force in the way that the force clause, as interpreted by Borden, requires.

The 8th Circuit disagreed, ruling:

Homicides committed with malice aforethought involve the “use of force against the person or property of another,” so 2nd-degree murder is a “crime of violence.” This holding implements the Supreme Court’s command to interpret statutes using not only “the statutory context, structure, history, and purpose,” but also “common sense…”

“Murder is the ultimate violent crime – irreversible and incomparable in terms of moral depravity,” the Court said. Borden quoted from an opinion by then-Judge Alito holding “the quintessential violent crimes, like murder or rape, involve the intentional use’ of force… Malice aforethought, murder’s defining characteristic, encapsulates the crime’s violent nature.”

“Murder is the ultimate violent crime – irreversible and incomparable in terms of moral depravity,” the Court said. Borden quoted from an opinion by then-Judge Alito holding “the quintessential violent crimes, like murder or rape, involve the intentional use’ of force… Malice aforethought, murder’s defining characteristic, encapsulates the crime’s violent nature.”

Murder is still a crime of violence. Only in federal law could such a question be debatable.

Janis v. United States, Case No. 22-2471, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 16993 (8th Cir. July 6, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root