We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

TAYLOR-MADE DECISION

The Supreme Court ruled yesterday in a 7-2 decision that an attempt to commit a crime of violence is not in itself a “crime of violence” for purposes of 18 USC § 924(c).

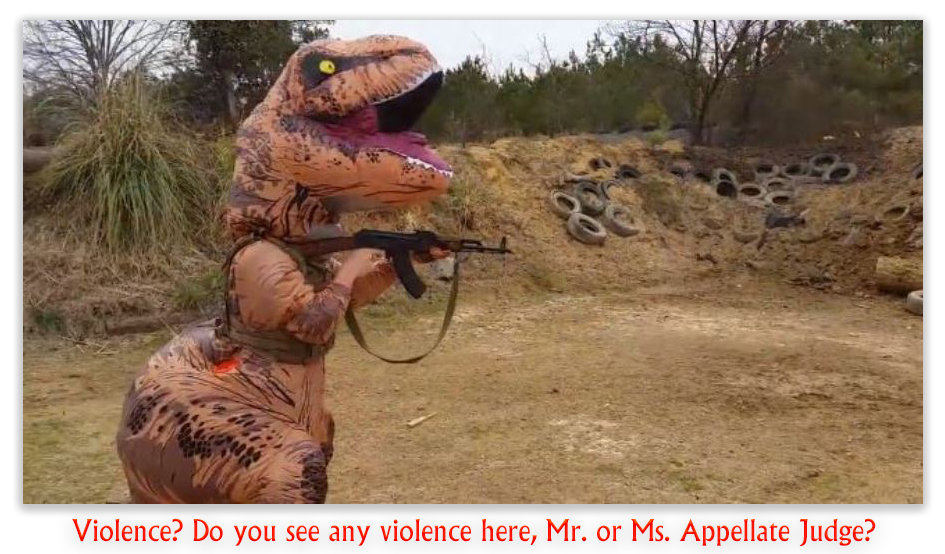

A little review: under 18 USC § 924(c), possessing, using or carrying a gun during and in relation to a crime of violence or drug offense will earn a defendant a mandatory minimum consecutive sentence of at least five years (and much worse if the defendant waves it around or fires it). A “crime of violence” is one that “has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another.”

A little review: under 18 USC § 924(c), possessing, using or carrying a gun during and in relation to a crime of violence or drug offense will earn a defendant a mandatory minimum consecutive sentence of at least five years (and much worse if the defendant waves it around or fires it). A “crime of violence” is one that “has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another.”

This fairly straightforward question of what constitutes a crime of violence has spawned a series of Supreme Court decisions since Johnson v. United States in 2015. The last words on the subject were United States v. Davis, a 2019 decision holding that conspiracy to commit a crime of violence was not a “crime of violence” that would support a conviction under 18 USC § 924(c), and last summer’s Borden v. United States (an offense that can be committed recklessly cannot be a “crime of violence,” because a “crime of violence” has to be committed knowingly or intentionally).

The Court has directed that interpretation of whether a statute constitutes a crime of violence is a decision made categorically. The Court’s “categorical approach” determines whether a federal felony may serve as a predicate “crime of violence” within the meaning of the statute if it “has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force.” This definition is commonly known as the “elements” clause.

The question is not how any particular defendant may have committed the crime. Instead, the issue is whether the federal felony that was charged requires the government to prove beyond a reasonable doubt as an element of its case, that the defendant used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force.

This approach has caused a lot of mischief. The facts underlying yesterday’s decision, Taylor v. United States, were particularly ugly. Justin Taylor, the defendant, went to a drug buy intending to rip off the seller of his drugs. Before he could try to rob the seller, the seller smelled a setup, and a gunfight erupted. Justin was wounded. The drug dealer was killed.

This approach has caused a lot of mischief. The facts underlying yesterday’s decision, Taylor v. United States, were particularly ugly. Justin Taylor, the defendant, went to a drug buy intending to rip off the seller of his drugs. Before he could try to rob the seller, the seller smelled a setup, and a gunfight erupted. Justin was wounded. The drug dealer was killed.

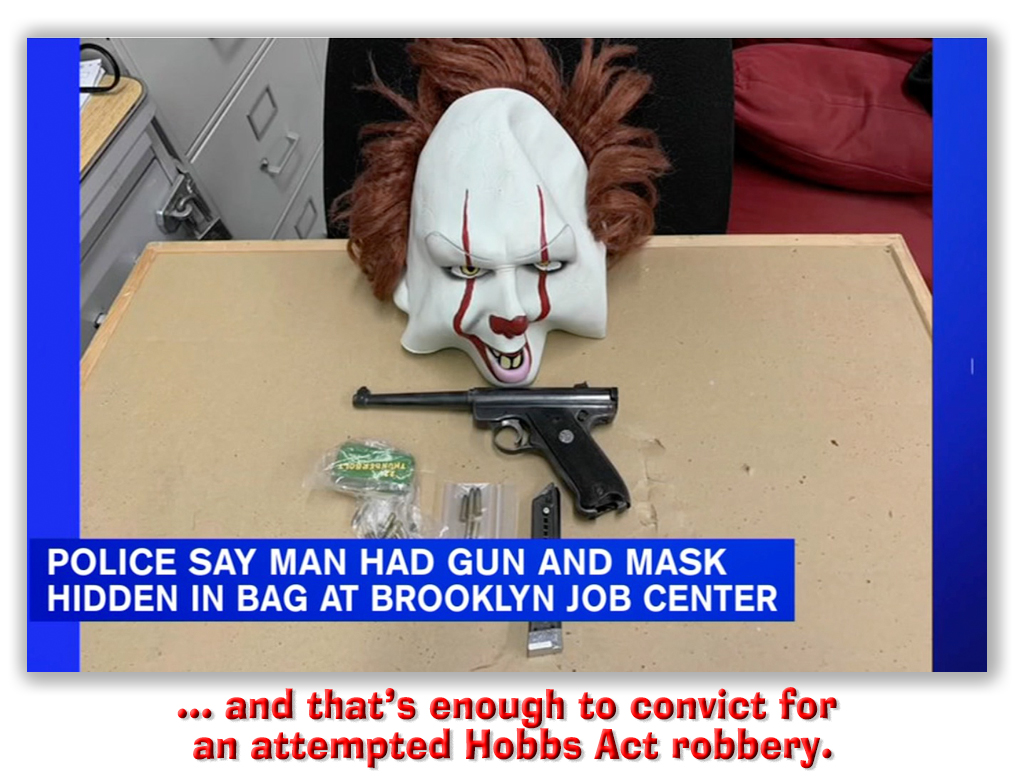

Because Justin never actually robbed the seller – he didn’t have time to do so – he was convicted of an attempted Hobbs Act robbery under 18 USC § 1951 (a robbery that affects interstate commerce) and of an 18 USC § 924(c) offense for using a gun during a crime of violence. Justin argued that while he was guilty of the attempted Hobbs Act robbery, he could not be convicted of a § 924(c) offense because it’s possible to commit an attempted robbery without actually using or threatening to commit a violent act. Under Borden and Davis, Justin argued, merely attempting a crime of violence was not itself a crime of violence.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court agreed.

Justice Gorsuch ruled that an attempted Hobbs Act robbery does not satisfy the “elements clause.” To secure a conviction for attempted Hobbs Act robbery, the government must prove that the defendant intended to complete the offense and completed a “substantial step” toward that end. An intention, the Court said, is just that and no more. And whatever a “substantial step” requires, it does not require the government to prove that the defendant used, attempted to use, or even threatened to use force against another person or his property. This is true even if the facts would allow the government to do so in many cases (as it obviously could have done in Taylor’s case).

The Court cited the Model Penal Code’s explanation of common-law robbery, which Justice Gorsuch called an “analogue” to the Hobbs Act. The MPC notes that “there will be cases, appropriately reached by a charge of attempted robbery, where the actor does not actually harm anyone or even threaten harm.” Likewise, the Supreme Court ruled, no element of attempted Hobbs Act robbery requires proof that the defendant used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force.

The Court cited the Model Penal Code’s explanation of common-law robbery, which Justice Gorsuch called an “analogue” to the Hobbs Act. The MPC notes that “there will be cases, appropriately reached by a charge of attempted robbery, where the actor does not actually harm anyone or even threaten harm.” Likewise, the Supreme Court ruled, no element of attempted Hobbs Act robbery requires proof that the defendant used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force.

Taylor raises interesting questions about “aiding and abetting.” In Rosemond v. United States, the Supreme Court ruled that a defendant can be convicted as an aider and abettor under 18 USC § 2 “without proof that he participated in each and every element of the offense.” Instead, Congress used language in the statute that “comprehends all assistance rendered by words, acts, encouragement, support, or presence… even if that aid relates to only one (or some) of a crime’s phases or elements.”

Taylor’s finding that attempted Hobbs Act robbery cannot support a § 924(c) conviction because a defendant can be convicted of the attempt without proof that he or she used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force, then it stands to reason that if the defendant can be convicted of aiding or abetting a Hobbs Act robbery without proof that he or she used, attempted to use, or threatened to use force, “aiding and abetting” likewise will not support a § 924(c) conviction.

In separate dissents, Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito argued that the lower court should have been reversed. Justice Thomas said the court’s holding “exemplifies just how this Court’s ‘categorical approach’ has led the Federal Judiciary on a ‘journey Through the Looking Glass,’ during which we have found many ‘strange things.’”

Indeed, a layperson would find it baffling that Justin could shoot his target to death without the government being able to prove he used a gun in a crime of violence. But Justice Thomas’s ire is misplaced. One should not blame the sword for the hand that wields it. Congress wrote the statute. It can surely change it if it is not satisfied with how the Court says its plain terms require its application.

Indeed, a layperson would find it baffling that Justin could shoot his target to death without the government being able to prove he used a gun in a crime of violence. But Justice Thomas’s ire is misplaced. One should not blame the sword for the hand that wields it. Congress wrote the statute. It can surely change it if it is not satisfied with how the Court says its plain terms require its application.

United States v. Taylor, Case No. 20-1459 2022 U.S. LEXIS 3017 (June 21, 2022).

– Thomas L. Root

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.