We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

3RD CIRCUIT FINDS A RACKETEERING CONSPIRACY IS NO CRIME OF VIOLENCE

Nelson Quinteros was being deported to his native El Salvador on the grounds that a prior criminal conviction under 18 USC § 1959(a)(6) was a crime of violence, and thus an “aggravated felony” under the immigration laws. (An aggravated felony conviction will get a non-citizen deported).

Sec. 1959(a)(6), a subsection of an offense entitled “Violent Crimes In Aid of Racketeering,” provides that whoever, for payment or to join or advance in a racketeering enterprise, “murders, kidnaps, maims, assaults with a dangerous weapon, commits assault resulting in serious bodily injury upon, or threatens to commit a crime of violence against any individual in violation of the laws of any State or the United States, or attempts or conspires so to do, shall be punished… for attempting or conspiring to commit a crime involving maiming, assault with a dangerous weapon, or assault resulting in serious bodily injury…”

Sec. 1959(a)(6), a subsection of an offense entitled “Violent Crimes In Aid of Racketeering,” provides that whoever, for payment or to join or advance in a racketeering enterprise, “murders, kidnaps, maims, assaults with a dangerous weapon, commits assault resulting in serious bodily injury upon, or threatens to commit a crime of violence against any individual in violation of the laws of any State or the United States, or attempts or conspires so to do, shall be punished… for attempting or conspiring to commit a crime involving maiming, assault with a dangerous weapon, or assault resulting in serious bodily injury…”

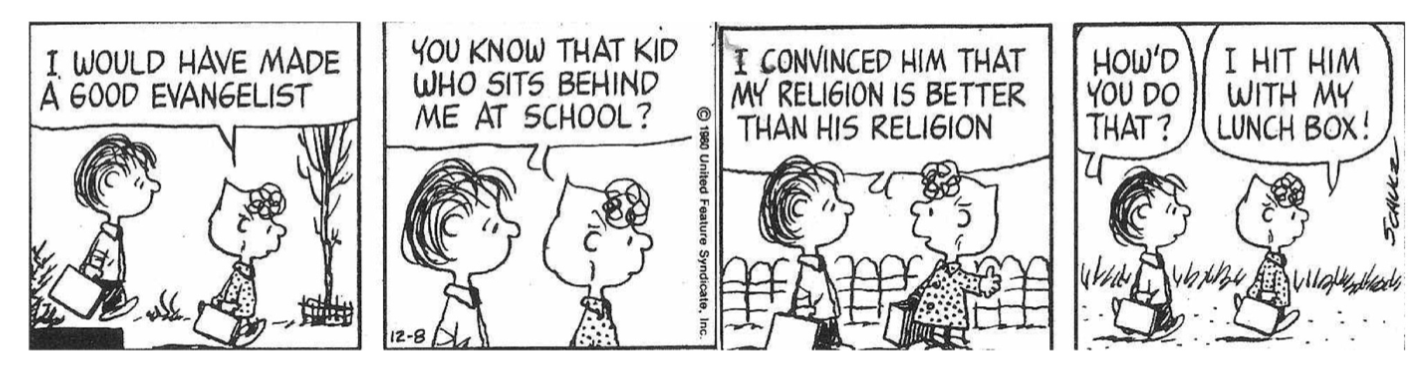

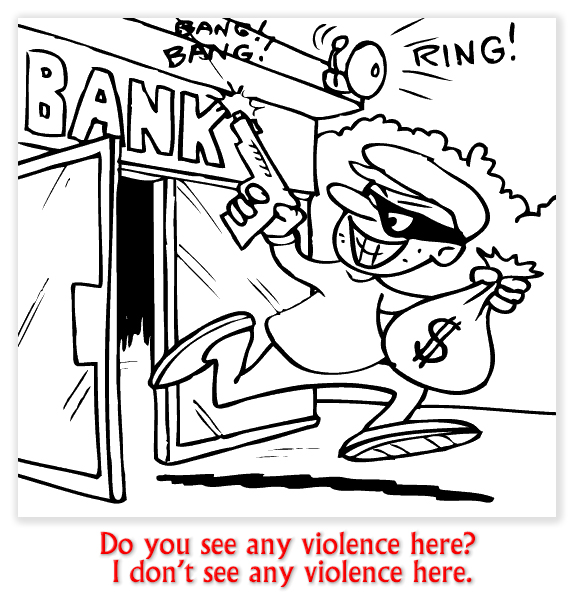

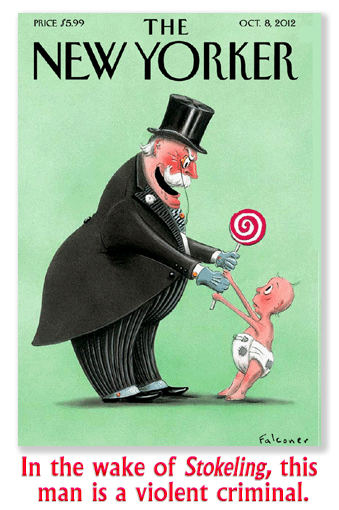

Sound violent? Well, yes, rather. But in the weird legal world that “crimes of violence” have inhabited since Curtis Johnson v. United States, back in 2010, sought to define what violence is, what appears to be a violent crime cannot be counted on to necessarily be a “crime of violence” under the statute.

The Board of Immigration Appeals originally held that Nelson’s § 1959(a)(6) conviction was a crime of violence under 18 USC § 16(b), a statute that defined what constituted a crime of violence under the criminal code. However, after the BIA decision on Nelson’s case, the Supreme Court in Sessions v. Dimaya threw out § 16(b) as unconstitutionally vague. That meant that the § 1959(a)(6) offense was no longer a crime of violence unless it could qualify under § 18 USC § 16(a). Last week, the 3rd Circuit ruled that Nelson’s prior conviction did not qualify as a crime of violence under that subsection, either.

Section 16(a) defines crime of violence as an offense that has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another, substantially the same definition used in 18 USC § 924(c) and in the Armed Career Criminal Act. “Looking at the least culpable conduct,” the Court wrote (as it must), “an individual could be convicted of conspiracy under 18 USC § 1959(a)(6) without the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force.” What’s more, because a § 1959(a)(6) conviction does not require that a defendant commit any overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy, the statute could conceivably punish for “evil intent alone.”

Section 16(a) defines crime of violence as an offense that has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another, substantially the same definition used in 18 USC § 924(c) and in the Armed Career Criminal Act. “Looking at the least culpable conduct,” the Court wrote (as it must), “an individual could be convicted of conspiracy under 18 USC § 1959(a)(6) without the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force.” What’s more, because a § 1959(a)(6) conviction does not require that a defendant commit any overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy, the statute could conceivably punish for “evil intent alone.”

In other words, Nelson and his cronies could sit around with a few brewskis talking about how they would later commit bodily mayhem on some old lady crossing the street. That would violate § 1959(a)(6), even if later, on the way to do so, they passed a storefront church and were saved, thus abandoning their lives of sin. The conspiracy offense would still have been committed, but nowhere would they have threatened or committed an act of violence.

Nelson’s case was about deportation, but its holding suggests that many of the statutes in Chapter 95 of the criminal code, which includes the Hobbs Act and murder-for-hire, may be vulnerable to a Mathis v. United States-type analysis in the wake of Johnson, Dimaya, and United States v. Davis.

The world of “crimes of violence” keeps getting stranger.

Quinteros v. Attorney General, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 37237 (3rd Cir. Dec.17, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root