We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

CRACK FSA RESENTENCING MUST CONSIDER MOVANT’S PRISON RECORD

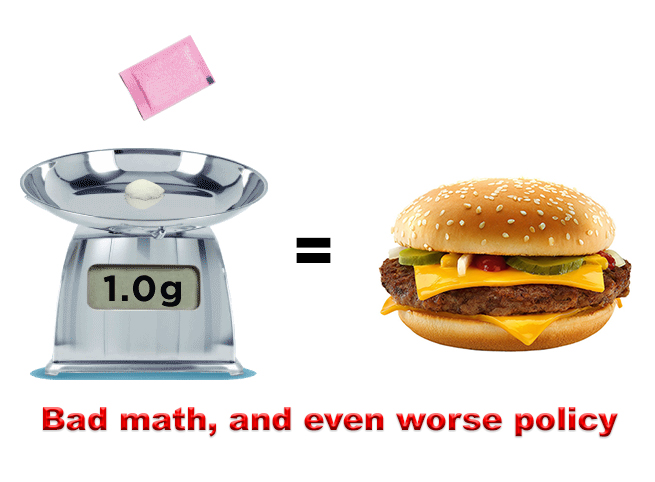

Shawn Williams was sentenced in 2005 to 262 months in prison for a crack cocaine trafficking offense. Five years later, Congress finally bowed to Sentencing Commission pressure and public opinion, passing the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). That Act changed the draconian penalties for crack cocaine (which had considered 10 grams of crack to be the equivalent of one kilogram of powder cocaine) to bring them more in line with other drug offenses.

Not that the change did much for Shawn. In order to satisfy some of the more puritanical members of the Senate – such as the unlamented former Sen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III – the changes made by the FSA were not retroactive. This meant that people like Shawn were serving sentences that were grossly disproportionate to sentences being imposed on people with the same drug quantity who were being sentenced after the FSA went into effect.

Not that the change did much for Shawn. In order to satisfy some of the more puritanical members of the Senate – such as the unlamented former Sen. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III – the changes made by the FSA were not retroactive. This meant that people like Shawn were serving sentences that were grossly disproportionate to sentences being imposed on people with the same drug quantity who were being sentenced after the FSA went into effect.

The First Step Act fixed that eight years later, making the FSA retroactive. Now, Shawn could apply to his sentencing court for relief, because the Act – when applied to Shawn – to reduced his statutory minimum sentence to 10 years from 20. However, for reasons not relevant to this blog, the FSA did not reduce his advisory Guidelines sentencing range.

Shawn nevertheless filed a motion to reduce his sentence under the retroactive FSA, arguing, among other things, that his good conduct in prison warranted a reduced sentence. He noted that he had not failed a single drug test, that he had helped 13 other prisoners earn their GEDs, and that he had held the same job for over eight years. The district court denied his motion, however, explaining that it had considered the 18 USC § 3553(a) sentencing factors (including Shawn’s prior drug convictions, and concluded that the 262-month sentence “remains sufficient and necessary to protect the public from future crimes of the defendant, to provide just punishment, and to provide deterrence.” The court did not address Shawn’s prison record.

A sidebar here: Back in 2011, the Supreme Court ruled in Pepper v. United States that “consistent with the principle that the punishment should fit the offender and not merely the crime… a sentencing judge [may] exercise a wide discretion in the sources and types of evidence used to assist him in determining the kind and extent of punishment to be imposed within limits fixed by law, particularly the fullest information possible concerning the defendant’s life and characteristics.” In other words, Pepper held, when a case comes back for resentencing – often years after the first sentencing, during which the defendant was doing time in prison – the sentencing court may consider the defendant’s prison record (such as good conduct and completion of educational or rehabilitative programs) in the resentencing.

But Pepper did not say that the district court was required to do so. The issue Shawn raised on appeal was whether the sentencing judge was at least required to acknowledge post-sentencing conduct raised by the defendant, and explain how that did or did not factor into the resentencing decision.

But Pepper did not say that the district court was required to do so. The issue Shawn raised on appeal was whether the sentencing judge was at least required to acknowledge post-sentencing conduct raised by the defendant, and explain how that did or did not factor into the resentencing decision.

Last week, the 6th Circuit reversed the sentencing court, sending the FSA resentencing back to the district court. The 6th held that while the district court “need not respond to every sentencing argument… the record as a whole must indicate the reasoning behind the court’s sentencing decision.” Here, the district court did not mention Shawn’s prison conduct, and “that conduct by definition occurred after his initial sentencing in 2005, which means that neither the record for his initial sentence nor for his First Step Act motion provides us any indication of the district court’s reasoning as to that motion.”

The case was remanded “for further consideration of Williams’ good-conduct argument.”

United States v. Williams, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 27219 (6th Cir. Aug 26, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

A few years ago, the 9th Circuit had ruled that the some of Ezralee’s Washington state convictions used back in 2006 to make her a career offender do not count toward career offender. As a result, Ezralee said, she should be resentenced without the career status, which should drop her from 262-327 to a 51-month range.

A few years ago, the 9th Circuit had ruled that the some of Ezralee’s Washington state convictions used back in 2006 to make her a career offender do not count toward career offender. As a result, Ezralee said, she should be resentenced without the career status, which should drop her from 262-327 to a 51-month range.

Even after passage of the

Even after passage of the