We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

EQUAL ACT AND MORE ACT MOVING FORWARD IN CONGRESS

It now looks like the EQUAL ACT (S.79), a bill to equalize crack and powder sentences, may have a ready path to passage.

Last week, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) signed onto the bill as a co-sponsor, although his plans to bring the bill to a floor vote are still not clear. The bill passed the House, 361-66, in September and President Joe Biden, who campaigned on criminal justice reform, is expected to sign the measure when it reaches his desk.

Last week, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) signed onto the bill as a co-sponsor, although his plans to bring the bill to a floor vote are still not clear. The bill passed the House, 361-66, in September and President Joe Biden, who campaigned on criminal justice reform, is expected to sign the measure when it reaches his desk.

Ten Senate Republicans, including Sen. Richard Burr (R-NC), who added his name last week, are co-sponsoring the bill, that would eliminate the federal sentencing disparity between drug offenses involving crack and powder cocaine. This paves the way for likely passage in the evenly divided Senate chamber, where 60 votes are required to pass most legislation.

It now “looks like you’d get to 60, really,” said Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), one of the ten GOP EQUAL Act sponsors. “This is the Democrats’ prerogative, it’d be nice if they would bring it to the floor.”

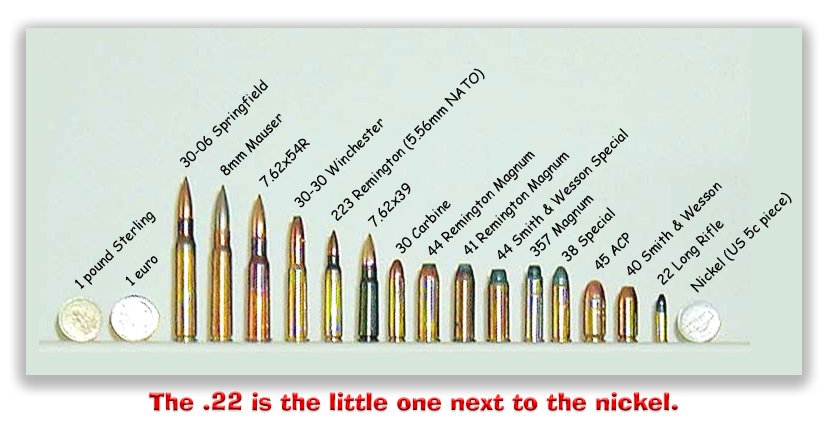

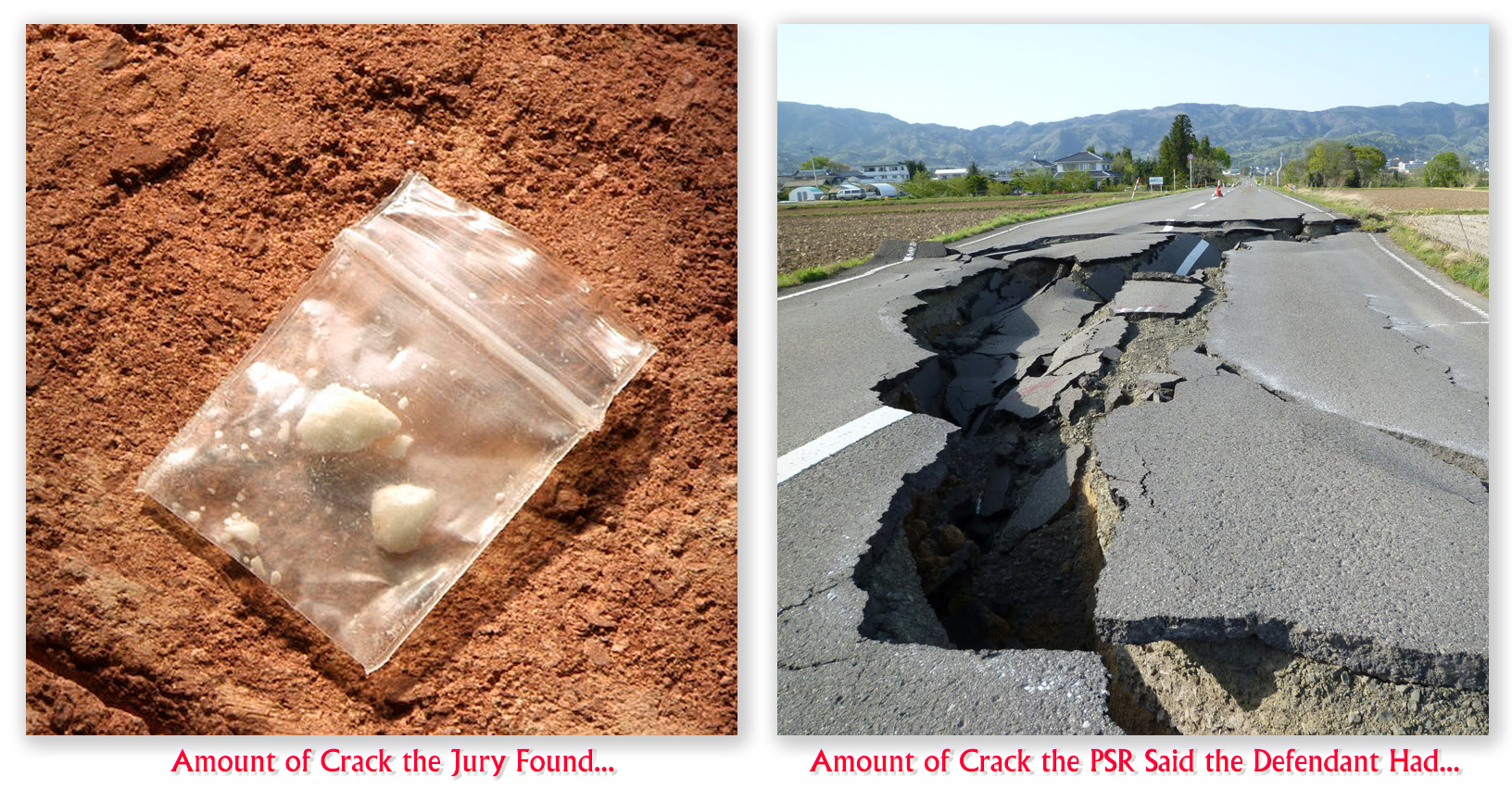

The bill, primarily sponsored by Judiciary Chairman Richard Durbin (D-IL) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), lowers the punishment for crack cocaine to match the thresholds for powder cocaine. In 2020, the Sentencing Commission found that 77% of crack cocaine trafficking offenders were black and 6% were white. Yet whites are more likely to use cocaine in their lifetime than any other group, according to the 2020 survey. Current law sets an 18-to-1 ratio between crack and powder cocaine, meaning anyone found with 28 grams of crack cocaine would face the same five-year mandatory prison sentence as a person found with 500 grams of powder cocaine.

Sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine were originally created with a 100-to-1 ratio, but in 2010, Congress reduced the sentencing disparity to 18-to-1 in the Fair Sentencing Act, but advocates have fought to further narrow the sentencing gap.

Sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine were originally created with a 100-to-1 ratio, but in 2010, Congress reduced the sentencing disparity to 18-to-1 in the Fair Sentencing Act, but advocates have fought to further narrow the sentencing gap.

EQUAL is likely to get a vote in the Senate before the midterms given the support of Schumer and the 10 GOP lawmakers, according to the Washington Times. The GOP support means the legislation is able to overcome a filibuster, provided all 50 Senate Democrats unite behind the effort. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who has been a maverick so far in this Session, also became a cosponsor last week.

Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman said in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog that it now seems the EQUAL Act “may have a ready path to passage.”

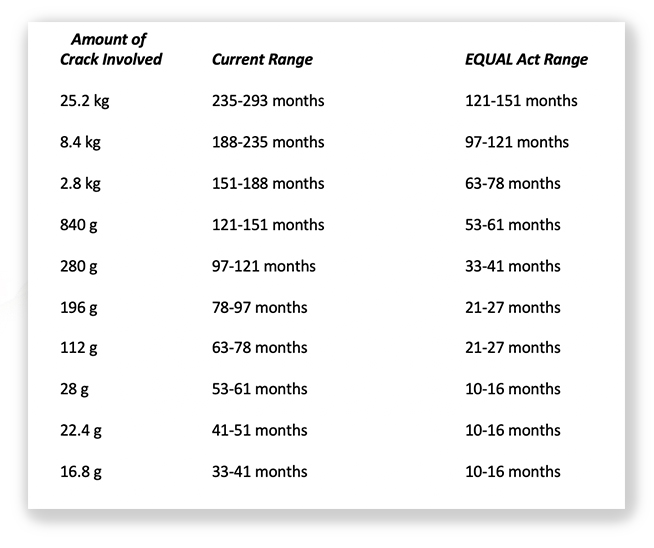

If enacted, the EQUAL Act would not only level federal sentences for future crack offenses but would retroactively slash prison time for those already doing time. The U.S. Sentencing Commission, which has analyzed the impact of the bill, estimates about 7,600 prisoners – nearly 5% of the federal prison population – would receive a sentence reduction. In most cases, overall crack prison sentences would be cut by at least one-third.

Meanwhile, a marijuana reform newsletter last week reported that a bill to federally legalize marijuana may be coming up for another House floor vote next week, The newsletter’s sources said that “nothing is yet set in stone, despite recent calls to bring the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act to the floor again this month.

Nevertheless, rumors of a floor vote – the second time that the MORE Act reached the full chamber after being approved in 2020 – are rife after congressional Democrats held a private session at a party retreat that included a panel centered on the reform legislation. The bill, which would remove cannabis from the list of controlled substances, cleared the House Judiciary Committee last September.

Nevertheless, rumors of a floor vote – the second time that the MORE Act reached the full chamber after being approved in 2020 – are rife after congressional Democrats held a private session at a party retreat that included a panel centered on the reform legislation. The bill, which would remove cannabis from the list of controlled substances, cleared the House Judiciary Committee last September.

Bloomberg, GOP Support Clears Senate Path for Bill on Cocaine Sentencing (March 23, 2022)

Washington Times, Schumer joins bipartisan push to cut federal prison time for nearly 7,800 crack cocaine traffickers (March 22, 2022)

Sentencing Law and Policy, Is Congress finally on the verge of equalizing crack and powder cocaine sentences? (March 23, 2022)

Marijuana Moment, Federal Marijuana Legalization Bill May Receive House Floor Vote Next Week, Sources Say (March 23, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root