We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

NO GUNS FOR HORSE THIEVES… BUT MAYBE FOR OTHERS

While upholding a felon-in-possession conviction against Ronnie Diaz, the 5th Circuit ruled last week that 18 USC § 922(g)(1) nevertheless may violate the 2nd Amendment in some cases.

Ron’s conviction was not his first felon-in-possession rodeo. In 2014, he did three years in state prison in 2014 for stealing a car and evading arrest. Four years later, he was caught breaking into a car while carrying a gun and a baggie of meth. He did two years in state for a Texas charge of possessing a firearm as a felon. (Yeah, it’s illegal there, too).

After a November 2020 traffic stop that got kicked up to the Feds, Ron was convicted of 21 USC § 841(a)(1) drug trafficking, an 18 USC 18 USC § 924(c) count for possessing a gun during a drug crime, and a § 922(g)(1) felon-in-possession. Ron moved to dismiss the § 922(g)(1) as unconstitutional under New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. The district court denied him.

The district court denied Ron’s Bruen motion. Ron appealed, and last week, the 5th Circuit agreed.

Bruen addressed whether a state law severely limiting the right to carry a gun in public violated the 2nd Amendment right to bear arms. When a law limits 2nd Amendment rights, Bruen held, the burden falls on the government to show that the law is “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” This involves addressing “how and why the regulations burden a law-abiding citizen’s right to armed self-defense.” In Bruen, the Court held that the plain text of the 2nd Amendment protects the right to bear arms in public for self-defense and that the government had failed to “identify an American tradition” justifying limiting such behavior.

Then in United States v. Rahimi, the Supreme Court last June ruled that 18 USC § 922(g)(8) – that prohibits people under domestic protection orders from having guns – passed the Bruen test. Comparing § 922(g)(8) to colonial “surety and going armed” laws that prohibited people from “riding or going armed, with dangerous or unusual weapons to terrify the good people of the land,” the Supreme Court held that § 922(g)(8) was analogous to such laws, only applied once a court has found that the defendant “represents a credible threat to the physical safety” and only applied only while a restraining order is in place.

Violating the “surety and going armed” laws could result in imprisonment. The 5th said that “if imprisonment was permissible to respond to the use of guns to threaten the physical safety of others, then the lesser restriction of temporary disarmament that § 922(g)(8) imposes is also permissible.”

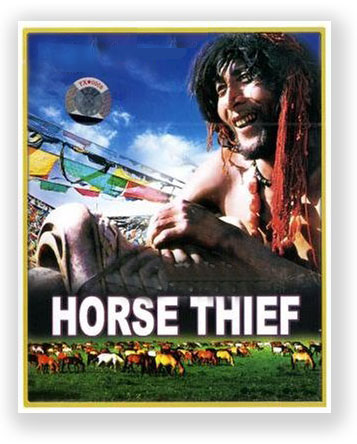

The 5th noted that “felony” is much too malleable a term to serve as a basis for deciding § 922(g)(1)’s constitutionality. Instead, it compared each of Ron’s prior convictions to colonial laws. Stealing a car, the Circuit decided, was analogous to colonial laws against horse thievery, and horse thieves in colonial America “were often subject to the death penalty.” Such laws “establish that our country has a historical tradition of severely punishing people like Diaz who have been convicted of theft,” meaning that a permanent prohibition on possessing guns passes 2nd Amendment muster.

The 5th noted that “felony” is much too malleable a term to serve as a basis for deciding § 922(g)(1)’s constitutionality. Instead, it compared each of Ron’s prior convictions to colonial laws. Stealing a car, the Circuit decided, was analogous to colonial laws against horse thievery, and horse thieves in colonial America “were often subject to the death penalty.” Such laws “establish that our country has a historical tradition of severely punishing people like Diaz who have been convicted of theft,” meaning that a permanent prohibition on possessing guns passes 2nd Amendment muster.

“Taken together,” the Circuit said, “laws authorizing severe punishments for thievery and permanent disarmament in other cases establish that our tradition of firearm regulation supports the application of § 922(g)(1) to Diaz.”

Considering the obverse, the Diaz opinion suggests that other offenses unknown in colonial times – like selling drugs, downloading child porn, securities fraud, or conspiracy to do anything illegal – could not trigger the felon-in-possession statute consistent with the 2nd Amendment. Requiring a court to parse a defendant’s priors in order to convict him of a § 922(g)(1) would make a confusing hash of any felon-in-possession case.

Writing in his Sentencing Policy and Law blog, Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman observed that “the 8th Circuit has categorically rejected 2nd Amendment challenges to § 922(g)(1)… whereas the 6th Circuit has upheld this law “as applied to dangerous people.” The 5th Circuit has now upheld the law… based on the fact that there were Founding era laws ‘authorizing severe punishments for thievery and permanent disarmament in other cases’… [T]he fact that three circuits have taken three different approaches to this (frequently litigated) issue is yet another signal that this matter will likely have to be taken up by SCOTUS sooner rather than later.”

United States v. Diaz, Case No. 23-50452, 2024 U.S. App. LEXIS 23725 (5th Cir., September 18, 2024)

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1 (2022)

United States v. Rahimi, 144 S. Ct. 1889, 219 L. Ed. 2d 351 (2024)

Sentencing Policy and the Law, Fifth Circuit panel rejects Second Amendment challenge to federal felon in possession for defendant with prior car theft offense (September 20, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root