We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WE’RE BA-A-A-CK…

… the nine Supreme Court justices will say this morning, the first Monday in October and the first day of the Court’s new year. The high court begins its new term – which lasts until June 30, 2022 but is known as “October Term 2021” – with hearing arguments on one federal criminal issue and granting review to another.

… the nine Supreme Court justices will say this morning, the first Monday in October and the first day of the Court’s new year. The high court begins its new term – which lasts until June 30, 2022 but is known as “October Term 2021” – with hearing arguments on one federal criminal issue and granting review to another.

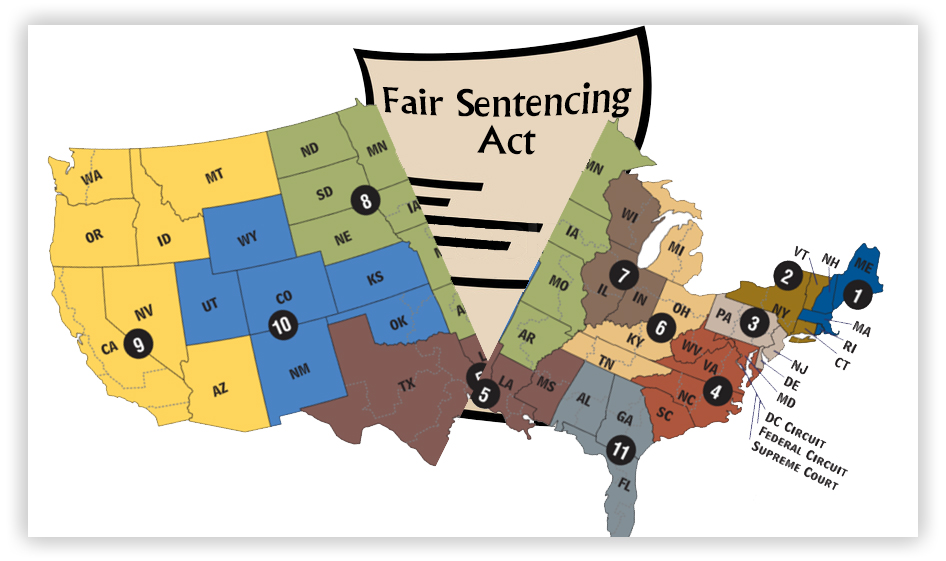

First, the grant of certiorari. Last week at its annual “long conference,” where the Court disposed of over 1,200 petitions seeking review of lower court decisions, the Supremes granted review to a First Step Act case. Back when Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 to reduce the disparity crack and powder cocaine sentences, it did not make the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive to the thousands of crack sentences already imposed.

In Section 404 of the 2018 First Step Act, Congress granted retroactivity at the discretion of the defendant’s sentencing judge, but did not specify any standards for the judge to apply in deciding whether to reduce a sentence. The question raised in Concepcion v. United States is whether, when a court is deciding whether to resentence a defendant under the Fair Sentencing Act, the court must or may consider intervening developments (such as prison record or rehabilitation efforts), or whether such developments only come into play (if at all) only after courts conclude that a sentence reduction is appropriate.

The 3rd, 4th, 10th, and DC circuits have held that district courts must consider all subsequent facts, and not just the changes to statutory penalties, when conducting Fair Sentencing Act resentencings. But in the 1st, 2nd, 6th, 7th and 8th circuits are only required to adopt the revised statutory maximum and minimum sentences for crack cocaine spelled out in the Fair Sentencing Act. In the 5th, 9th, and 11th circuits, district courts are prohibited from considering any intervening case law or updated sentencing guidelines, and are not required to consider any post-sentencing facts during resentencings.

Don’t expect a decision before June 2022.

Now, for today’s argument. The Supreme Court will begin its term hearing argument in Wooden v United States. Defendant Wooden broke into a storage facility and stole from 10 separate storage units many years ago. When he was found in possession of a gun years later, the district court sentenced him under the Armed Career Criminal Act to 15 years, because it found that he committed three violent offenses – the breaking into the 10 storage units – “on occasions different from one another.” The Court of Appeals agreed, arguing that the crimes were committed on separate “occasions” because “Wooden could not be in two (let alone ten) of [the storage units] at once.”

This has long been the worst aspect of the ACCA, itself as well-meaning but lousy law. A number of circuits hold that crimes are committed on different “occasions” for ACCA purposes when they are committed “successively rather than simultaneously.” Other circuits, however, looked beyond temporality and instead considered whether the crimes were committed under sufficiently different circumstances.

This has long been the worst aspect of the ACCA, itself as well-meaning but lousy law. A number of circuits hold that crimes are committed on different “occasions” for ACCA purposes when they are committed “successively rather than simultaneously.” Other circuits, however, looked beyond temporality and instead considered whether the crimes were committed under sufficiently different circumstances.

The Supreme Court will resolve the Circuit split. A decision is expected early next year, and – if the Court agrees defendant Wooden, a number of people serving ACCA sentences may be filing 28 USC § 2255 or 28 USC § 2241 petitions seeking reduced sentences.

Wooden v. United States, Case No. 20-5279 (Supreme Ct., argued Oct 4, 2021)

Concepcion v. United States, Case No. 20-1650 (Supreme Ct., certiorari granted Sep 30, 2021)

Law360, Supreme Court Will Seek To Solve Crack Resentencing Puzzle (September 30, 2021)

SCOTUSBlog.com, What’s an “occasion”? Scope of Armed Career Criminal Act depends on the answer. (October 1, 2021)

– Thomas L. Root

End Run: John Ham filed a

End Run: John Ham filed a

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.

There is little doubt that this issue, and probably the whole “attempt” furball, is headed for the Supreme Court.