We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

ORAL ARGUMENTS SUGGEST SCOTUS WILL SIDE WITH ACCA DEFENDANTS

The Supreme Court appears to be leaning toward Armed Career Criminal Act defendants who argue that a “serious drug felony” predicate for the 15-year mandatory minimum has to be determined by today’s standards rather than a backward-facing analysis.

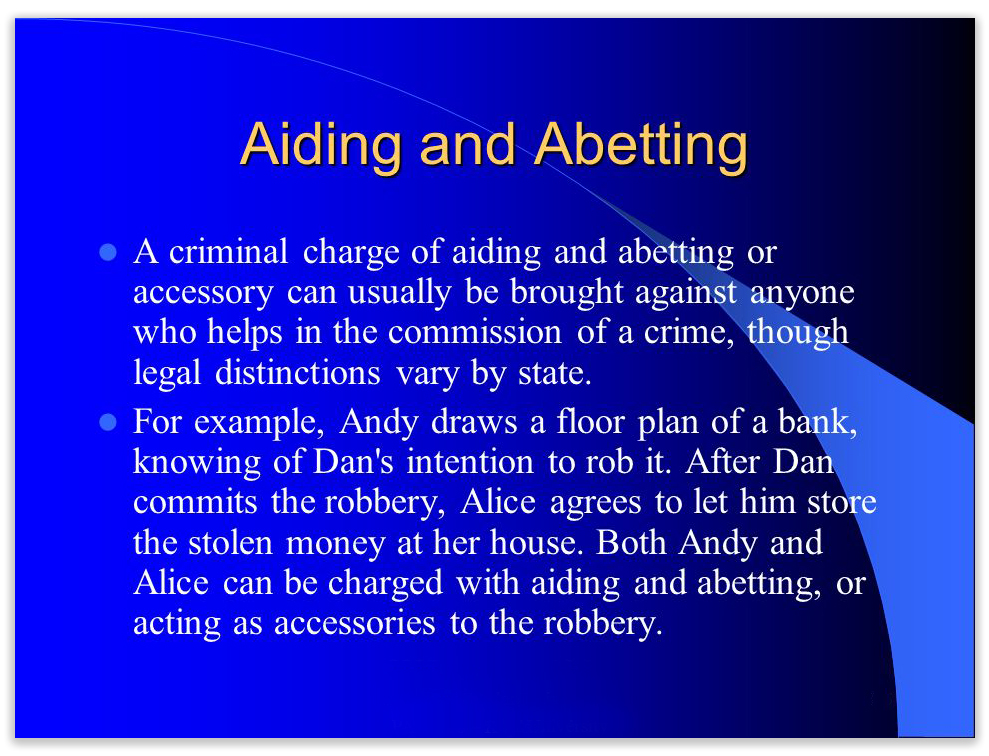

The ACCA directs that someone violating 18 USC § 922(g) by being a felon in possession of a gun or ammo who has three prior convictions for crimes of violence or a serious drug offense, is subject to a sentence starting at 15 years and going up to life in prison. Brown v. United States and Jackson v. United States, cases that were combined for argument because of the common question they raise, focus on “serious drug offense.” The Court heard arguments on the cases the Monday after Thanksgiving.

The ACCA directs that someone violating 18 USC § 922(g) by being a felon in possession of a gun or ammo who has three prior convictions for crimes of violence or a serious drug offense, is subject to a sentence starting at 15 years and going up to life in prison. Brown v. United States and Jackson v. United States, cases that were combined for argument because of the common question they raise, focus on “serious drug offense.” The Court heard arguments on the cases the Monday after Thanksgiving.

A “serious drug offense” felony that counts as one of the three predicates qualifying a defendant for the ACCA isn’t listed in the statute. Instead, the definition is based on whether the controlled substance involved is in the federal drug schedules administered by the Dept of Justice. As Justice Kagan put it during the argument, “What’s going to be a controlled substance next year is not necessarily the same as this year.”

Defendant Brown was once convicted of a state marijuana offense that he says no longer qualifies under the current federal drug laws as “serious.” Defendant Jackson makes the same claim about a prior state cocaine conviction. They both argue that whether a prior state drug felony is a “serious drug offense” should be judged by the schedule that exists as of the date of ACCA sentencing, not as of the date of the prior conviction.

Depending on which version of the schedule applies, a state drug conviction may or may not count as a predicate. The defendants gave the justices three options for deciding which schedule applied: the one in force at the time of the state drug offense, the one in force when the defendant committed the 18 USC § 922(g) crime or the one that applied when the defendant was sentenced for the federal gun crime.

The Trace – a gun control advocacy website – noted that for criminal justice reform groups, the Supremes’ 2022 New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen decision came with a silver lining, raising doubt about “many of the policies that have fed the country’s mass incarceration crisis… Many criminal justice reformers are not necessarily advocating for more guns or gun ownership… but they also don’t want gun laws applied unfairly or used to target black and brown communities already scarred by the ‘war on drugs’.”

A majority of the justices appeared unlikely to agree with the government that whether a conviction was a “serious drug felony” should be judged at the time of the previous drug conviction. They seemed to agree with Jackson’s attorney that a change in the federal drug schedules seemed to be “in effect” an amendment to the ACCA itself. “So if in effect it’s an amendment of ACCA, why is it treated differently or less exactingly than an actual amendment of ACCA?” Justice Clarence Thomas asked.

Whether the Court will determine that the definition of the prior drug felony is fixed as of the time of the felon-in-possession offense or as of the time of sentencing is a tougher read. That won’t be clear until the opinion issues sometime next spring.

Brown v. United States, Case No. 22-6389 (Sup. Ct, argued November 27, 2023)

Jackson v. United States, Case No. 22-6640 (Sup. Ct, argued November 27, 2023)

New York Times, Justices Search for Middle Ground on Mandatory Sentences for Gun Crimes, (November 27, 2023)

The Trace, Supreme Court Hears Arguments on Mandatory Minimums for Drug Offenses, Gun Possession (November 29, 2023)

Bloomberg Law, Justices Back Criminal Defendants in Firearm Sentencing Rule (November 27, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root

The Supreme Court held in the 2009

The Supreme Court held in the 2009