We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

IS DOJ TRYING TO AVOID A SUPREME COURT 922(G)(1) CHALLENGE?

Voltaire wrote (roughly translated) that perfection is the enemy of good enough. Disturbing evidence is emerging that President Trump’s administration is adopting that standard in fighting to keep 18 USC § 922(g)(1) – the felon-in-possession ban that is the most enforced gun law on the federal books – in place.

Several DOJ Supreme Court filings last month urged SCOTUS to reject review of F-I-P cases asking whether § 922(g)(1) can be applied to nonviolent felons consistent with New York State Rifle & Postal Assn v. Bruen, arguing in part that the DOJ’s yet-unformed proposal to use 18 USC § 925(c) to restore gun rights for some felons is good enough.

Several DOJ Supreme Court filings last month urged SCOTUS to reject review of F-I-P cases asking whether § 922(g)(1) can be applied to nonviolent felons consistent with New York State Rifle & Postal Assn v. Bruen, arguing in part that the DOJ’s yet-unformed proposal to use 18 USC § 925(c) to restore gun rights for some felons is good enough.

In March, DOJ ginned up an ad hoc rights restoration program to reward actor and Trump supporter Mel Gibson by giving him back his gun rights despite a domestic violence conviction. Opposition to the decision cost Pardon Attorney Elizabeth Oyer her job. Ultimately, the agency restored the gun rights of 10 people (including Gibson), noting cryptically that each person had submitted “materials… seeking either a pardon or relief from federal firearms disabilities, and it is established to [the Attorney General’s] satisfaction that each individual will not be likely to act in a manner dangerous to public safety and that the granting of the relief to each individual would not be contrary to the public interest.”

DOJ has neither issued any regulations on how former felons might apply for gun rights restoration nor has it responded to multiple requests for details. But that has not stopped DOJ from citing this undisclosed and opaque process as an additional reason for the Supreme Court not to grant review in any felon-in-possession 2nd Amendment cases.

DOJ has neither issued any regulations on how former felons might apply for gun rights restoration nor has it responded to multiple requests for details. But that has not stopped DOJ from citing this undisclosed and opaque process as an additional reason for the Supreme Court not to grant review in any felon-in-possession 2nd Amendment cases.

On April 25, Solicitor General John Sauer opposed a petition for cert from a 4th Circuit § 922(g)(1) as-applied denial. “Although there is some disagreement among the courts of appeals regarding whether § 922(g)(1) is susceptible to individualized as-applied challenges, that disagreement is shallow,” SG Sauer wrote, “[a]nd any disagreement among the circuits may evaporate given the Dept of Justice’s recent reestablishment of the administrative process under 18 USC § 925(c) for granting relief from federal firearms disabilities.”

The Reload, a gun law newsletter, said, “The Trump Administration’s preferred approach to gun rights for convicted felons [is] one that would grant a high degree of discretion and centralize the decision-making within the executive branch rather than through a widely applicable legal precedent, as gun-rights advocates have long sought in court. As a result, it may undermine many of the movement’s best cases by undercutting the claims of sympathetic plaintiffs.”

The Government seems to be deliberately avoiding picking a Supreme Court § 922(g)(1) fight that it doesn’t think it can win. I reported previously that DOJ decided against filing for cert after losing a 3rd Circuit en banc decision on § 922(g)(1)’s constitutionality. In a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee, the Solicitor General said, “In the case of Bryan Range, a Pennsylvania man with a 30-year-old state misdemeanor conviction for understating his income on a food stamp application, the Third Circuit ruled the ban violated his Second Amendment rights… The Department of Justice has concluded that a petition for a writ of certiorari is not warranted in this case,” Solicitor General John Sauer wrote a letter sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee last month. “The Third Circuit’s decision is narrow, leaving § 922(g)(1) untouched except in the most unusual applications.”

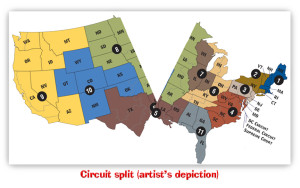

Two weeks ago, the 9th Circuit in United States v. Duarte joined the 4th, 8th, 10th and 11th Circuits in refusing to distinguish between violent and non-violent criminals for the purposes of F-I-P constitutionality. The Reload said, “Assuming Duarte appeals the decision, which seems likely, it could present a compelling opportunity for the High Court to address the now deepened circuit split with the 3rd, 5th, and 6th Circuits, which have all recognized an ability for individualized challenges to the federal ban by non-violent offenders.”

Last week, a cert petition filed in Vincent v. Bondi may derail the DOJ’s efforts to avoid a Supreme Court reckoning on F-I-P. Melynda Vincent is the poster child for an as-applied challenge to § 922(g)(1), a woman who was convicted 17 years ago of felony bank fraud for passing a fraudulent $498 check when she was homeless and an addict. She got no jail time. Since then, she rehabbed, became a mom, earned several master’s degrees, and started her own rehab counseling firm. Nevertheless, § 922(g)(1) permanently keeps her from possessing a gun to protect her family.

Last week, a cert petition filed in Vincent v. Bondi may derail the DOJ’s efforts to avoid a Supreme Court reckoning on F-I-P. Melynda Vincent is the poster child for an as-applied challenge to § 922(g)(1), a woman who was convicted 17 years ago of felony bank fraud for passing a fraudulent $498 check when she was homeless and an addict. She got no jail time. Since then, she rehabbed, became a mom, earned several master’s degrees, and started her own rehab counseling firm. Nevertheless, § 922(g)(1) permanently keeps her from possessing a gun to protect her family.

The Reload said that SCOTUS may find ruling on F-I-P easier “by accepting a case like Vincent’s, where even most hardline gun-control advocates would have a difficult time arguing she is too dangerous for consideration.”

DOJ may oppose Vincent by arguing that its new § 925(c) gun rights restoration procedure, whatever it may be, is good enough to take care of her wish to possess a gun. But if § 922(g)(1) violates the 2nd Amendment as applied to Melynda Vincent, then some amorphous and opaque DOJ procedure to restore gun rights on the whim of the AG hardly cures the violation. What’s more, it means that some, if not many, of the tens of thousands of federal prisoners doing time for a potentially unconstitutional offense will be left out in the cold.

The “good enough” of a § 925(c) rights restoration will not be sufficient substitute for the “perfection” of a Supreme Court ruling on § 922(g)(1).

Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, Hunt v. United States, Case No 24-6818 (filed April 25, 2025)

The Reload, The Coming DOJ-SCOTUS Showdown Over Felon Gun Rights (May 18, 2025)

Solicitor General Letter to Sen Richard Durbin (April 11, 2025)

Petition for Certiorari, Vincent v. United States, Case No. 24-1155 (filed May 12, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root