We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SENTENCING COMMISSION ROCKET DOCKET

Showing that a federal prisoner has an ‘extraordinary and compelling’ reason for grant of compassionate release is critical to getting a sentence reduction grant under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A). That statute also requires that any grant be consistent with “applicable policy statements” of the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

Showing that a federal prisoner has an ‘extraordinary and compelling’ reason for grant of compassionate release is critical to getting a sentence reduction grant under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A). That statute also requires that any grant be consistent with “applicable policy statements” of the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

This is where it’s been sticky. The USSC has one policy statement (USSG § 1B1.13) addressing compassionate release, adopted well before the compassionate release statute was changed by the First Step Act. The same month Congress passed First Step (December 2018), the USSC lost its quorum as multiple members’ terms expired. President Trump nominated some new members a few months later, but the Senate did not approve them. That condition lasted until last spring, when President Biden nominated a complete slate of new members.

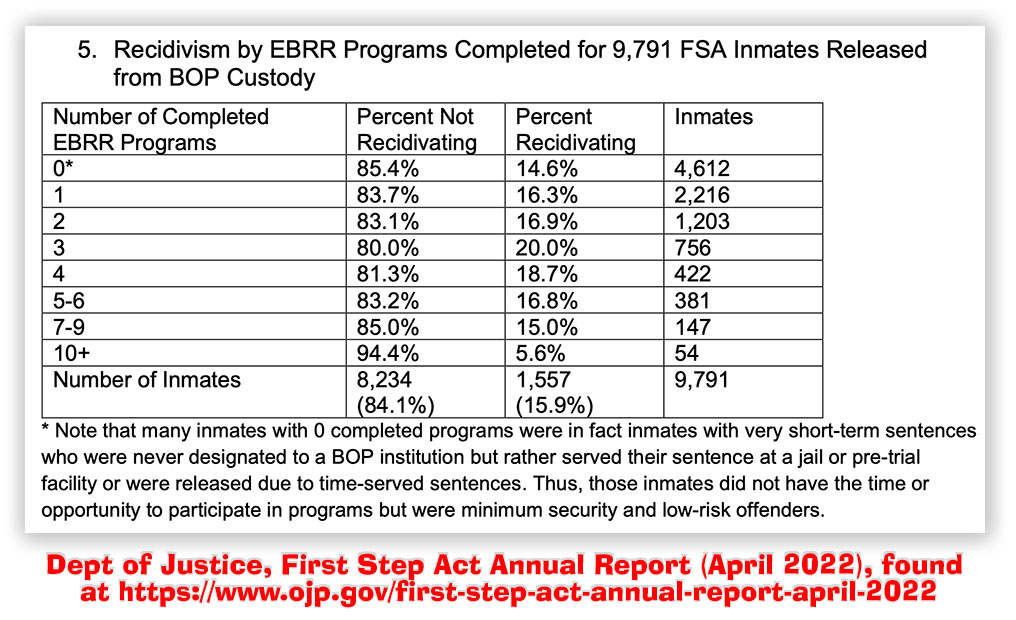

Without a quorum, the USSC could not modify § 1B1.13 to account for the changes that First Step made in the § 3582(c)(1)(A). Almost all courts responded by holding that the old § 1B1.13 was no longer an “applicable policy statement” and thus didn’t bind the courts. In a way, that was liberating to the people filing compassionate release motions, because courts were freed from § 1B1.13’s restrictive definition of what constituted “extraordinary and compelling” reasons.

Without a quorum, the USSC could not modify § 1B1.13 to account for the changes that First Step made in the § 3582(c)(1)(A). Almost all courts responded by holding that the old § 1B1.13 was no longer an “applicable policy statement” and thus didn’t bind the courts. In a way, that was liberating to the people filing compassionate release motions, because courts were freed from § 1B1.13’s restrictive definition of what constituted “extraordinary and compelling” reasons.

But without a USSC policy statement moderating district court responses, compassionate release grants since 2019 have been characterized by wide disparity. In Oregon, for instance, about 62% of compassionate release filings have been granted. In the Middle District of Georgia, on the other hand, only about 1.5% have been granted.

The new USSC said last its top priority was to amend § 1B1.13, and in January, the Commission issued a draft § 1B1.13 for public comment that contained some very prisoner-friendly proposals and options. The proposed change was part of an extensive set of draft Guidelines amendments that spanned more than a hundred pages of text. The public comment period ended two weeks ago, with over 1,600 pages of comments filed on the compassionate release proposal alone.

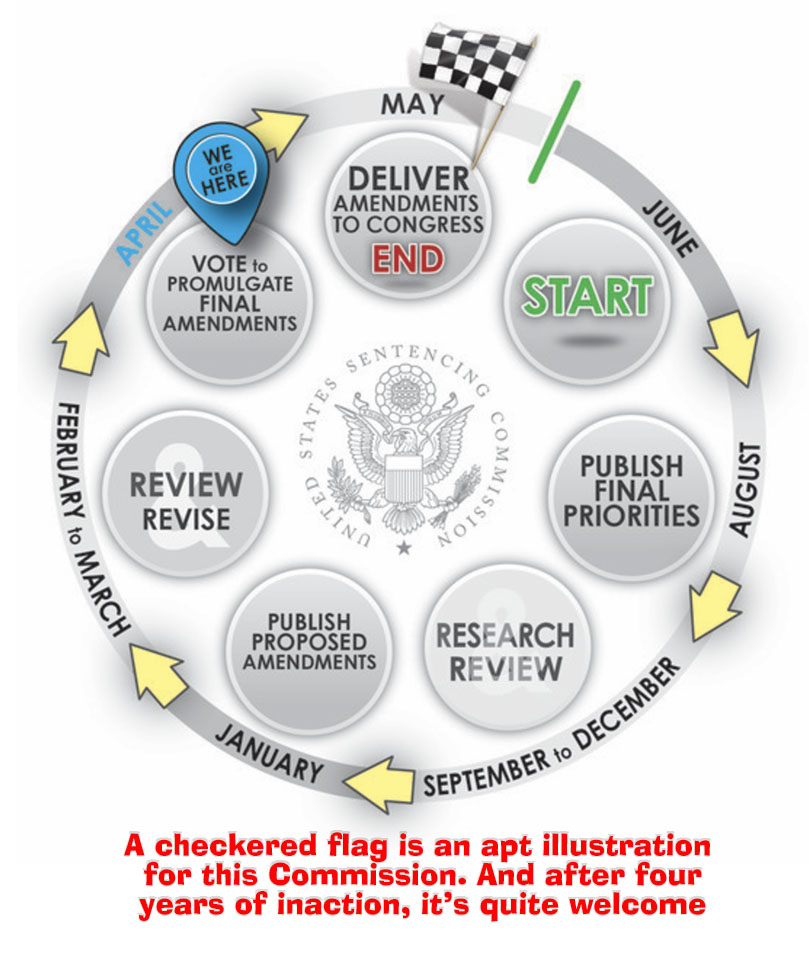

The USSC usually rolls out its proposal Guidelines amendments by May 1st. Under 28 USC § 994(p), the amendments go to Congress, which then has 180 days to reject them. If Congress does nothing (which is almost always the case), the changes become effective.

But this new USSC is in a hurry to get things done. Last week, the Commission announced an April 5 meeting at which the final § 1B1.13 (and all of the other draft proposed amendments) will be adopted.

But this new USSC is in a hurry to get things done. Last week, the Commission announced an April 5 meeting at which the final § 1B1.13 (and all of the other draft proposed amendments) will be adopted.

If the amendment package goes to Congress that same day, they could become effective as early as Monday, Oct 2nd.

USSC, Public Meeting – April 5, 2023 (March 24, 2023)

– Thomas L. Root