We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

FCI SHERIDAN IS POSTER CHILD FOR BOP DYSFUNCTION

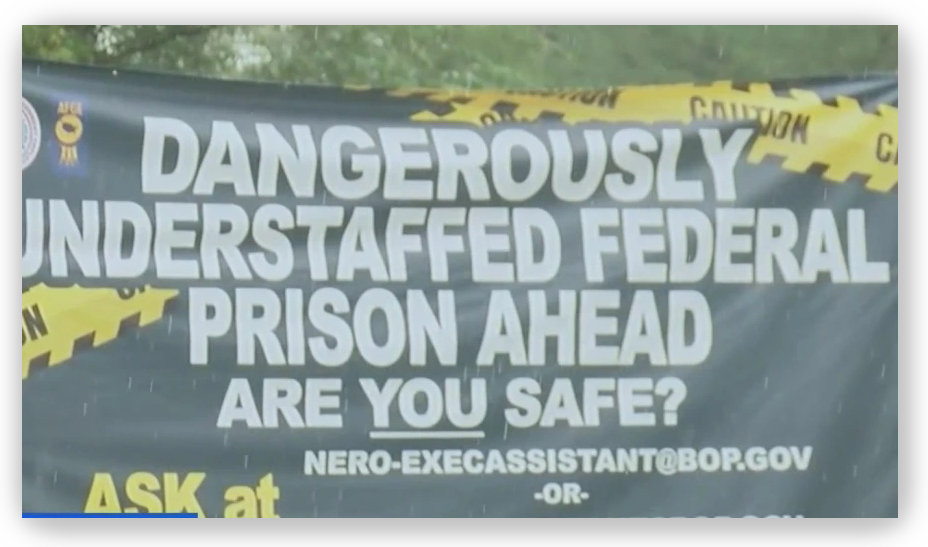

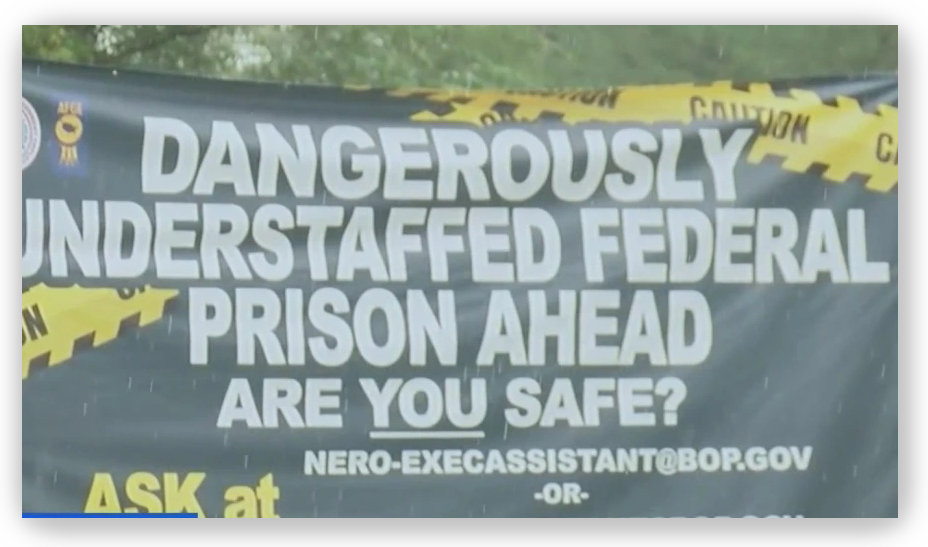

The Department of Justice Inspector General released a report yesterday that found “serious operational deficiencies,” including “alarming staffing shortages” at the Bureau of Prisons facility in Sheridan, Oregon.

The Department of Justice Inspector General released a report yesterday that found “serious operational deficiencies,” including “alarming staffing shortages” at the Bureau of Prisons facility in Sheridan, Oregon.

One might say that BOP dysfunction is trending.

FCI Sheridan, a medium-security men’s prison with an adjacent detention center and prison camp, was Inspector General Michael Horowitz’s third unannounced prison inspection since the IG began the program at FCI Waseca (a women’s facility) last May. That report was followed by last November’s findings on a surprise inspection at FCI Tallahassee, another women’s facility. Now, after inspecting two female facilities, the IG has focused on the other 92% of inmates, the men.

IG Horowitz is taking Jan and Dean to heart: Two girls for every boy.

The dominant theme of the Sheridan report is staffing shortages and the effect the problem has on healthcare. providing a glimpse into the depth of inmates’ frustrated enterprise:

For example, we found that, just prior to our inspection, an inmate feigned a suicide attempt in order to receive medical attention for an untreated ingrown hair that had become infected. When finally examined after the feigned suicide attempt, he required hospitalization for 5 days to treat the infection.

No doubt the prisoner was punished for his desperate caper, but only he got out of the hospital. The BOP is unlikely to have acknowledged that it shared any responsibility for turning the simple ingrown hair removal into a $50,000+ medical expense. The inmate was right: you gotta do what you gotta do, and that includes doing what it takes to get urgent healthcare from an overtaxed and uncaring bureaucracy.

No doubt the prisoner was punished for his desperate caper, but only he got out of the hospital. The BOP is unlikely to have acknowledged that it shared any responsibility for turning the simple ingrown hair removal into a $50,000+ medical expense. The inmate was right: you gotta do what you gotta do, and that includes doing what it takes to get urgent healthcare from an overtaxed and uncaring bureaucracy.

The Sheridan findings are plenty harrowing, even without the illustration of the faked suicide attempt. The IG summarized them as:

• Healthcare Worker Shortages: Because of short staffing in the Health Services Department, a backlog existed of 725 lab orders for blood draws or urine collection and 274 pending x-ray orders at the time of the inspection. “These backlogs cause medical conditions to go undiagnosed and leave providers unable to appropriately treat their patients,” the report said.

• High Correctional Officer Vacancy Rate: A shortage of correctional officers meant that “inmates must routinely be confined to their cells during daytime hours and are therefore often unable to participate in programs and recreational activities.” What’s more, the shortage meant that “FCI Sheridan did not always have available Correctional Officers to escort inmates to external medical providers.”

• Psychology Services and Education Department Staffing Shortages: “[S]erious shortages among drug treatment program employees prevented the institution from offering its Residential Drug Treatment Program (RDAP) to inmates… We also found long waitlists, some exceeding over 500 names, for other trauma-related mental health, anger management, and work skills classes.”

• Sexual Misconduct Reporting: FCI Sheridan did not centrally track the number of all allegations of inmate-on-inmate sexual misconduct reported to employees. The failure “undermines the ability of… the BOP to collect data consistent with Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) standards that would allow them to assess and improve the effectiveness of sexual misconduct prevention efforts.”

NPR reported that the staffing shortages “are among the biggest obstacles facing the federal prison system, according to this report, and contribute to other challenges at Sheridan and the more than 120 facilities like it.” Horowitz told NPR that “[i]t’s a problem that is at least 20 years in the making. It’s not going to get fixed overnight. But what these inspections show us how serious the problem has now become.” Horowitz said. “It is deeply concerning when you go to a facility like Sheridan and you hear from the staff, correctional officers, health care workers, educators, that they can’t do the jobs that they’re there to do and they want to do.”

After this third IG inspection, a trend is developing:

• Both the Tallahassee and the Sheridan inspections found “serious operational deficiencies” and “alarming” problems. At FCI Tallahassee, the alarming conditions were with the facility’s execrable food service. At Sheridan, staff shortages were “alarming.” The IG is able to be frugal, reusing the same descriptors for multiple prisons.

• All three inspections included the same disclaimer: “We did not make recommendations in this report because in our prior work we have recommended that the BOP address many of these issues at an enterprise level.” In other words, the IG was reporting on endemic BOP problems that exist throughout the system. The Sheridan report parrots the prior reports, conceding that “[m[ost of the significant issues we found at FCI Sheridan were consistent with findings the OIG has made in other recent BOP oversight work, which we have reported on publicly.”

Nothing new here, either folks.

• We’re starting to suss out the inspection tempo. The Waseca report was last May, the Tallahassee report was in November 2023, and Sheridan was this week. It looks like the IG is inspecting about two facilities a year. Certainly, there are resource considerations: it takes people to kick open the prison doors. Horowitz told a National Press Club audience last March that “[m]y 500 personnel [are] comprised mostly of auditors and law enforcement agents. We also have evaluators and inspectors. One of the things we’re doing now, by the way, is unannounced inspections of federal prisons, and those are much smaller groups compared to the auditors and the agents.”

• All three inspections found serious staffing problems, which is hardly news. The Waseca and Sheridan inspections found long delays in providing First Step Act and drug abuse programming to inmates, which the Sheridan report said resulted in inmates having “limited opportunities to prepare for successful reentry into our communities. “ All three reports found that shortages of Healthcare staff had “negatively affected healthcare treatment” (as the Tallahassee report put it). The Waseca findings were that “staff shortages in both FCI Waseca’s health services and psychology services departments… have caused delays in physical and mental health care treatment.”

• The IG reports all seem to come with some sexy news hook. Waseca’s was inmates living in basements and under leaky pipes. Tallahassee’s was moldy food and rat droppings in the chow hall. Sheridan’s was the feigned suicide attempt to get healthcare.

“What we’ve seen over and over again, in our unannounced inspections of the Bureau of Prisons is the challenges they face in meeting their mission of making prisons safe and secure, and preparing inmates for reentry back into society,” Horowitz told NPR in an interview reported yesterday. “And this is another case where we’ve seen severe challenges that they face in fulfilling those missions.”

“What we’ve seen over and over again, in our unannounced inspections of the Bureau of Prisons is the challenges they face in meeting their mission of making prisons safe and secure, and preparing inmates for reentry back into society,” Horowitz told NPR in an interview reported yesterday. “And this is another case where we’ve seen severe challenges that they face in fulfilling those missions.”

DOJ Inspector General, Inspection of the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ Federal Correctional Institution Sheridan (May 22, 2024)

NPR, Lack of staffing led to ‘deeply concerning’ conditions at federal prison in Oregon (May 22, 2024)

National Press Foundation, ‘The Truth Still Matters’: Justice Department Inspector General Highlights Non-Partisan Work (March 15, 2024)

– Thomas L. Root

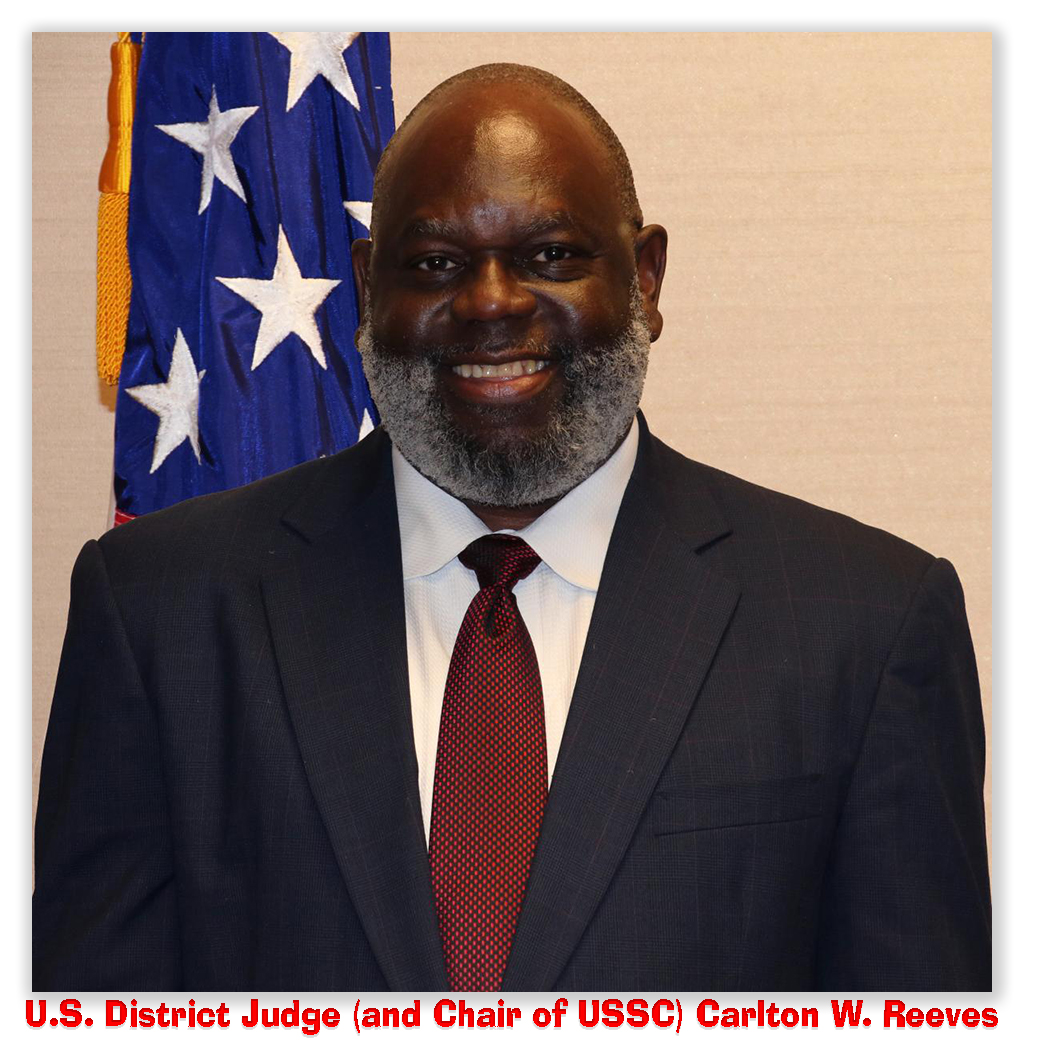

United States District Judge Carlton Reeves (Southern District of Mississippi), who happens to also be chairman of the U.S. Sentencing Commission, issued a plea for assistance last week:

United States District Judge Carlton Reeves (Southern District of Mississippi), who happens to also be chairman of the U.S. Sentencing Commission, issued a plea for assistance last week: Writing in his Sentencing Policy and Law blog, Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman said last week that “the message from the Commission seems pretty clear: it is prepared to, and is perhaps even eager to, start (re)considering any and all aspects of the federal sentencing system.”

Writing in his Sentencing Policy and Law blog, Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman said last week that “the message from the Commission seems pretty clear: it is prepared to, and is perhaps even eager to, start (re)considering any and all aspects of the federal sentencing system.”