We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SENTENCING COMMISSION ADOPTS AMENDMENTS BUT DROPS METH GUIDELINE CHANGE

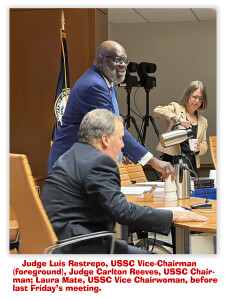

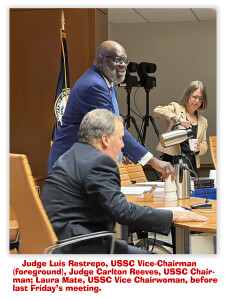

The bad news first: At last Friday’s U.S. Sentencing Commission meeting, the Commission did not vote on – in fact, did not even mention – the amendment it studied last summer and proposed in January to change the existing 2-level Guidelines enhancement for high methamphetamine purity levels. This means that there will be no change in the meth guidelines until November 2026 at the earliest (and maybe not even then).

The bad news first: At last Friday’s U.S. Sentencing Commission meeting, the Commission did not vote on – in fact, did not even mention – the amendment it studied last summer and proposed in January to change the existing 2-level Guidelines enhancement for high methamphetamine purity levels. This means that there will be no change in the meth guidelines until November 2026 at the earliest (and maybe not even then).

What the Commission did do: The USSC is amending Guideline § 2D1.1 to cap the drug tables at Level 32 if the defendant had a mitigating role in the offense (that is, received a role reduction under USSG § 3B1.2 for a minor or minimal role). More critically, the Commission – concerned that courts have applied the § 3B1.2 role reduction too sparingly over the years – is adding commentary directing that a § 3B1.2(a) reduction is generally warranted

if the defendant’s primary function in the offense was plainly among the lowest level of drug trafficking functions, such as serving as a courier, running errands, sending or receiving phone calls or messages, or acting as a lookout… A § 3B1.2(b) reduction is generally warranted if the defendant’s primary function in the offense was performing another low-level trafficking function, such as distributing controlled substances in user-level quantities for little or no monetary compensation or with a primary motivation other than profit (such as being motivated by an intimate or family relationship, or by threats or fear to commit the offense).

This is a welcome change. Sentencing courts have been surprisingly stingy over the years in applying minor role reductions. The Commission is saying that the drug guidelines should focus more on role in the offense and less on drug quantity (a metric that prosecutors have found is easy to manipulate).

The other significant change for the people already sentenced is to supervised release. The Commission is urging courts to apply supervised release where needed rather than reflexively, guidance which would dramatically reduce the number of defendants to whose cases it is added to the end of a sentence.

The other significant change for the people already sentenced is to supervised release. The Commission is urging courts to apply supervised release where needed rather than reflexively, guidance which would dramatically reduce the number of defendants to whose cases it is added to the end of a sentence.

The supervised release change would adopt an individualized approach to decisions on early termination of supervised release, making getting off supervision after a year much easier for defendants. The proposed changes resolve the Circuit split on whether a releasee must show extraordinary reasons supporting termination, instead directing a court to perform an “individualized assessment of the need for ongoing supervision” and ending supervision if it determines that “termination is warranted by the conduct of the defendant and in the interest of justice.”

In determining a defendant’s criminal history, prior convictions are counted as different offenses even if sentenced at the same time if they were separated by an “intervening arrest.” The 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 11th Circuits have held that a citation or summons following a traffic stop does not qualify as an intervening arrest. In the 7th Circuit, however, if a defendant is arrested for selling crack on the street corner on Tuesday, makes bail Tuesday night, gets a speeding ticket on Wednesday, and is arrested again for selling crack on Thursday, those two arrests have added six criminal history points to the defendant’s Guidelines calculations for what in most other Circuits would be scored as a 3-point criminal history, essentially part of a continuing offense. The 7th says that a traffic stop is enough to trigger the “intervening arrest” standard.

The Commission has proposed an amendment holding that a traffic stop, followed by the issuance of a summons, is not an arrest for criminal history purposes.

Under USSG § 2B3.1(b)(4)(B), an enhancement in a robbery sentence is called for if a victim is physically restrained. The Commission proposes amending the enhancement to provide that the psychological coercion of possessing a firearm alone is not enough. Instead, the increase will apply only where “any person’s freedom of movement was restricted through physical contact or confinement, such as being tied, bound, or locked up, to facilitate the commission of the offense or to facilitate escape.”

Under USSG § 2B3.1(b)(4)(B), an enhancement in a robbery sentence is called for if a victim is physically restrained. The Commission proposes amending the enhancement to provide that the psychological coercion of possessing a firearm alone is not enough. Instead, the increase will apply only where “any person’s freedom of movement was restricted through physical contact or confinement, such as being tied, bound, or locked up, to facilitate the commission of the offense or to facilitate escape.”

No decision was made on the retroactivity of any of the changes, but the Commission proposes study and comment on whether to make the drug minimal role, criminal history, and physical restraint amendments retroactive. That decision will be made this summer.

So what’s my beef about opacity? Jonathan Wroblewski described it well in an incisive Sentencing Matters Substack:

In this 40th anniversary year of the Sentencing Reform Act (SRA), and 20th anniversary year of the Supreme Court’s decision in Booker, the Commission said it would be reflecting on the core goals of the Sentencing Reform Act, the progress that has been made towards meeting them, and what actions might be taken now, and in the future, to further them. It sounded like a big deal… The published proposals made clear that the Commission was seriously considering making fundamental change to the guidelines system…

With expectations high, last Friday, the Commission’s amendment year came to an end with a rather short and quite opaque public meeting, unbecoming given the importance of the issues at stake and the process leading up to it. There were votes on amendment proposals for sure, but almost no explanation from commissioners for the consequential choices they were making. It turned out to be quite a disappointment.

With expectations high, last Friday, the Commission’s amendment year came to an end with a rather short and quite opaque public meeting, unbecoming given the importance of the issues at stake and the process leading up to it. There were votes on amendment proposals for sure, but almost no explanation from commissioners for the consequential choices they were making. It turned out to be quite a disappointment.

First, there was no discussion of the Commission’s thinking and how it arrived at its decisions. The Commission spent two and half days in deliberations behind closed doors, and then in a public meeting of less than a half hour, explained nothing of how those deliberations resulted in the actions taken and not taken. Judges, practitioners, Members of Congress, advocates, inmates, family members, and academics spent countless hours developing and submitting written comments to the Commission, and there was virtually no explanation of how those comments were considered. Second, the Commission in the end did not even address the categorical approach. No matter how many times the Commission places the issue on its priorities – and it has over and again for over a decade – it just can’t seem to find a fix. And again, no explanation.

Third, the Commission did not address the unwarranted disparities in methamphetamine sentencing identified by numerous commentors. This seemed especially perplexing given Judge Reeves’ own detailed decision in United States v. Robinson, holding that the methamphetamine purity enhancement had ceased to have any meaning. And again, no explanation. Fourth, the Commission made no fundamental reform to the drug guideline or to Step One of any other guideline. It did take steps to ensure that drug offenders who play a mitigating role are not over-punished. But the Commission has tried this before – numerous times, in fact – and it is far from clear that the steps taken will make a significant difference in drug sentencing policy.

I seldom quote at such length from another work, but Mr. Wroblewski’s Substack is worthy of it, and in fact is worthy of a full read by anyone affected by the Sentencing Commission’s work.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Amendments to the Sentencing Guidelines (Preliminary) (April 11, 2025)

WHNT, U.S. Sentencing Commission approves revisions to federal sentencing guidelines (April 11, 2025)

Jonathan Wroblewski, Sentencing Matters Substack (April 14, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root

Back in 2024, the Sentencing Commission proposed a slate of four proposed Guidelines changes to be retroactive. However, at the USSC’s August 2024 meeting, the retroactivity for the four Guideline changes — covering acquitted conduct, gun enhancements, 18 USC § 922(g)/drug/18 § USC 924(c) joint convictions, and a beneficial change in the drug Guidelines — did not go forward because of philosophical differences in how to approach retroactivity.

Back in 2024, the Sentencing Commission proposed a slate of four proposed Guidelines changes to be retroactive. However, at the USSC’s August 2024 meeting, the retroactivity for the four Guideline changes — covering acquitted conduct, gun enhancements, 18 USC § 922(g)/drug/18 § USC 924(c) joint convictions, and a beneficial change in the drug Guidelines — did not go forward because of philosophical differences in how to approach retroactivity. Unfortunately, the request does not solicit public comment on the Commission’s underlying approach to retroactivity, and thus, the current proceeding is unlikely to resolve the retroactivity backlog any time soon.

Unfortunately, the request does not solicit public comment on the Commission’s underlying approach to retroactivity, and thus, the current proceeding is unlikely to resolve the retroactivity backlog any time soon.