We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THREE CRIMES CAN BE ONE OCCASION, SUPREME COURT SAYS

When Thomas Jefferson bought 530 million acres for $15 million in the Louisiana Purchase, he was violating his own sense of the proper limitations on federal authority.

When Thomas Jefferson bought 530 million acres for $15 million in the Louisiana Purchase, he was violating his own sense of the proper limitations on federal authority.

The deal, however, was a steal: a lousy 3¢ an acre. It was just too good to pass up. Jefferson said at the time, “It is incumbent on those who accept great charges to risk themselves on great occasions.”

What if Jefferson’s purchase really was a steal, and he actually burgled 530 million acres from the French? Would he have committed a burglary on 530 million different occasions, or just 530 million burglaries at one time, on one “occasion?”

Talk about your angels on the head of a pin! But, arcane or not, this seemingly hyper-technical question yesterday – one with real-world consequences for many federal defendants – was addressed yesterday by the Supreme Court. A unanimous bench threw out an Armed Career Criminal Act sentencing enhancement for a man whose three predicate crimes of violence occurred during a single “occasion.”

Talk about your angels on the head of a pin! But, arcane or not, this seemingly hyper-technical question yesterday – one with real-world consequences for many federal defendants – was addressed yesterday by the Supreme Court. A unanimous bench threw out an Armed Career Criminal Act sentencing enhancement for a man whose three predicate crimes of violence occurred during a single “occasion.”

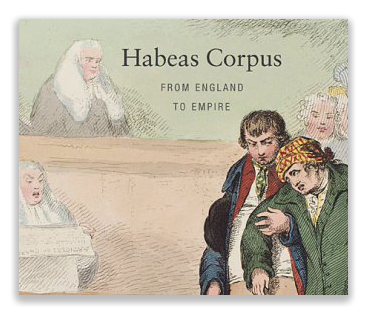

The ACCA provides that the mandatory minimum sentence for a defendant convicted of an 18 USC 922(g) firearms offense – commonly known as felon-in-possession – is 15 years to life if the defendant has three prior serious drug offenses or crimes of violence. The statute – 18 USC 924(e) – holds that the three prior offenses must have occurred on “on occasions different from one another.”

The problem is that courts have taken an increasingly narrow view of what “different occasions” might be.

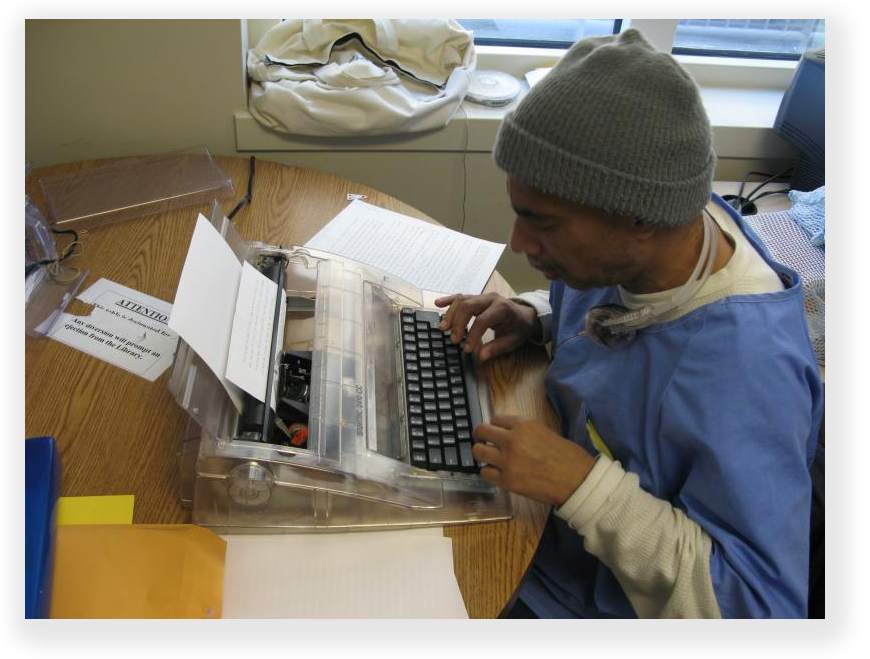

In 1997, Dale Wooden broke into a self-storage facility and burgled ten individual storage units. The State of Georgia convicted Dale of ten counts of burglary in a single state indictment. He received one sentence.

Seventeen years later, police found a gun in Dale’s house. The federal government charged him with felon-in-possession under 18 USC § 922(g)(1) and – because of the prior burglaries – prosecutors sought an enhanced ACCA sentence of 15 years. Absent the ACCA, Dale would have faced a Guidelines sentencing range of 27-33 months. He got 15 years (180 months).

Seventeen years later, police found a gun in Dale’s house. The federal government charged him with felon-in-possession under 18 USC § 922(g)(1) and – because of the prior burglaries – prosecutors sought an enhanced ACCA sentence of 15 years. Absent the ACCA, Dale would have faced a Guidelines sentencing range of 27-33 months. He got 15 years (180 months).

Dale’s trial court held that each burglary occurred on a different occasion, because a new burglary did not occur until the old one had been completed. As a result, one night’s illegal frolic made Dale an armed career criminal.

Yesterday’s decision turned on the meaning of § 924(e). Justice Kagan, writing for the court, said Dale’s burglary convictions arose from a single criminal episode and thus did not count as multiple occasions. She complained that the government’s view that any time offenses occurred seriatim the occasions were separate gutted the “occasions different from one another” standard:

By treating each temporally distinct offense as its own occasion, the Government goes far toward collapsing two separate statutory conditions. Recall that ACCA kicks in only if (1) a §922(g) offender has previously been convicted of three violent felonies, and (2) those three felonies were committed on “occasions different from one another.” §924(e)(1). In other words, the statute contains both a three-offense requirement and a three-occasion requirement. But under the Government’s view, the two will generally boil down to the same thing: When an offender’s criminal history meets the three-offense demand, it will also meet the three-occasion one. That is because people seldom commit—indeed, seldom can commit—multiple ACCA offenses at the exact same time. Take burglary. It is, just as the Government argues, “physically impossible” for an offender to enter different structures simultaneously. (citation omitted). Or consider crimes defined by the use of physical force, such as assault or murder. Except in unusual cases (like a bombing), multiple offenses of that kind happen one by one by one, even if all occur in a short spell. The Government’s reading, to be sure, does not render the occasions clause wholly superfluous; in select circumstances, a criminal may satisfy the elements of multiple offenses in a single instant. But for the most part, the Government’s hyper-technical focus on the precise timing of elements—which can make someone a career criminal in the space of a minute—gives ACCA’s three-occasions requirement no work to do.

Justice Kagen as well argued that the history of the ACCA supported her view. For the first four years of its existence, the “ACCA asked only about offenses, not about occasions. Its enhanced penalties, that is, kicked in whenever a §922(g) offender had three prior convictions for specified crimes—in the initial version, for robbery or burglary alone, and in the soon-amended version, for any violent felony or serious drug offense.” But after a court enhanced a sentence under the ACCA for six burglaries committed at once (see Petty v. United States, 481 U.S. 1034, 1034-1035 (1987), Congress amended ACCA to add the occasions clause, requiring that the requisite prior crimes occur on “occasions different from one another.”

Justice Kagen as well argued that the history of the ACCA supported her view. For the first four years of its existence, the “ACCA asked only about offenses, not about occasions. Its enhanced penalties, that is, kicked in whenever a §922(g) offender had three prior convictions for specified crimes—in the initial version, for robbery or burglary alone, and in the soon-amended version, for any violent felony or serious drug offense.” But after a court enhanced a sentence under the ACCA for six burglaries committed at once (see Petty v. United States, 481 U.S. 1034, 1034-1035 (1987), Congress amended ACCA to add the occasions clause, requiring that the requisite prior crimes occur on “occasions different from one another.”

Yesterday’s decision was unanimous, although four justices — Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett — declined to join some of Kagan’s opinion, meaning they disagreed with some of her reasoning.

So how does a court tell whether the occasions are different or the same? Kagan called the inquiry that must be made “multi-factored in nature.” She wrote

Timing of course matters, though not in the split-second, elements-based way the Government proposes. Offenses committed close in time, in an uninterrupted course of conduct, will often count as part of one occasion; not so offenses separated by substantial gaps in time or significant intervening events. Proximity of location is also important; the further away crimes take place, the less likely they are components of the same criminal event. And the character and relationship of the offenses may make a difference: The more similar or intertwined the conduct giving rise to the offenses—the more, for example, they share a common scheme or purpose—the more apt they are to compose one occasion.

Timing of course matters, though not in the split-second, elements-based way the Government proposes. Offenses committed close in time, in an uninterrupted course of conduct, will often count as part of one occasion; not so offenses separated by substantial gaps in time or significant intervening events. Proximity of location is also important; the further away crimes take place, the less likely they are components of the same criminal event. And the character and relationship of the offenses may make a difference: The more similar or intertwined the conduct giving rise to the offenses—the more, for example, they share a common scheme or purpose—the more apt they are to compose one occasion.

For the most part, applying this approach will be straightforward and intuitive. In the Circuits that have used it, we can find no example (nor has the Government offered one) of judges coming out differently on similar facts. In many cases, a single factor—especially of time or place—can decisively differentiate occasions. Courts, for instance, have nearly always treated offenses as occurring on separate occasions if a person committed them a day or more apart, or at a “significant distance.” (citation omitted). In other cases, the inquiry just as readily shows a single occasion, because all the factors cut that way. That is true, for example, in our barroom-brawl hypothetical, where the offender has engaged in a continuous stream of closely related criminal acts at one location. Of course, there will be some hard cases in between, as under almost any legal test. When that is so, assessing the relevant circumstances may also involve keeping an eye on ACCA’s history and purpose…

So where an ACCA defendant (as in one case with which I am familiar) broke into a strip mall and burgled one store, then pushed through the wall to another, it will be pretty easy to claim it was one occasion. In another case I worked on once, the defendant sold crack on the same street corner, was arrested for three undercover buys in 16 days. Different occasions? That one will be a lot closer.

Because yesterday’s decision interprets a statute, it will be retroactive on collateral review, meaning that people already convicted of an ACCA offense may challenge their sentence. Expect a wave of post-conviction litigation arising from this decision, in large part because the government has been so heavy-handed in charging ACCA enhancements where a more prudent prosecuting authority might not have been.

Wooden v. United States, No. 20-5279, 2022 U.S. LEXIS 1421 (March 7, 2022)

SCOTUSBlog, Court rejects enhanced sentence under Armed Career Criminal Act for man who broke into storage facility (March 7, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root

Unfortunately, the hyper-technical circuit policy that lets a defendant argue for hours against imposition of a

Unfortunately, the hyper-technical circuit policy that lets a defendant argue for hours against imposition of a