We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

CLEMENCY CRITICISM RISES AS CHRISTMAS APPROACHES

Business Insider noted last week that “at this point in his presidency, Joe Biden has pardoned just two sentient beings: Peanut Butter and Jelly, 40-pound turkeys from Jasper, Indiana.”

Not that prior presidents have done much better. Trump, by contrast, had pardoned three at this point in his presidency: two turkeys and one former sheriff. Clinton, Obama, and George W. Bush all waited until at least their second year in office before granting clemency to a human being.

Not that prior presidents have done much better. Trump, by contrast, had pardoned three at this point in his presidency: two turkeys and one former sheriff. Clinton, Obama, and George W. Bush all waited until at least their second year in office before granting clemency to a human being.

That’s not because Biden can’t find candidates. About 17,000 petitions are pending, 2,000 of which have been filed in the past year.

Last week, Kevin Ring of FAMM, Sakira Cook of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, and others met with White House staff to turn up the pressure. The meeting appears to have been frustrating for Ring. During an NPR roundtable last week on criminal justice reform, he noted that Biden has thus far even resisted clemency for CARES Act detainees. “To me, it’s a bellwether,” Ring said. “Because if the administration won’t address this and address it immediately, I don’t know what hope we can have that other things are going to get done.”

NPR noted that the BOP population has increased by about 5,000 since Biden took office.

Progressives in the House of Representatives, unhappy with a clemency system they say is too slow and deferential to prosecutors, last week proposed the creation of an independent panel they hope would depoliticize and expedite pardons.

The “FIX Clemency Act,” HR 6234, was introduced last Friday by Rep. Cori Bush (D-Missouri), Vice Chair of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass), and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY). The bill calls for a nine-person board that would be responsible for reviewing petitions for clemency and issuing recommendations directly to the president. The recommendations would also be made public in an annual report to Congress. At least one member of the panel would be someone who was previously incarcerated.

The “FIX Clemency Act,” HR 6234, was introduced last Friday by Rep. Cori Bush (D-Missouri), Vice Chair of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass), and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY). The bill calls for a nine-person board that would be responsible for reviewing petitions for clemency and issuing recommendations directly to the president. The recommendations would also be made public in an annual report to Congress. At least one member of the panel would be someone who was previously incarcerated.

That might work… if you could convince the President to appoint anyone to it. Last week, Law360 went after Biden for having yet to nominate anyone to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which is “keeping a potentially key player in justice reform on the sidelines, according to legal experts.”

The article points out that the USSC “hasn’t had a full roster of seven commissioners for nearly half a decade and has lacked the minimum four commissioners needed to pass amendments to its advisory federal sentencing guidelines since the beginning of 2019.” As a result, an agency whose job is to evaluate the criminal justice system’s operations and potentially drive reform has been taken off the field, Law 360 quoted Ohio State University law professor and sentencing expert Doug Berman as saying.

The USSC currently has only one voting member, Senior U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer, who will have to leave next October, regardless of whether anyone has been named to the Commission or not.

The USSC currently has only one voting member, Senior U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer, who will have to leave next October, regardless of whether anyone has been named to the Commission or not.

During another NPR roundtable last week, NPR reporter Asma Khalid said of criminal justice reform, “You know, I cover the White House. And I will say, I don’t see this as really being an issue at the forefront, at least not from what I’ve heard publicly from them.”

The leadership vacuum is perhaps best reflected in rudderless Congressional action. Last September, the House of Representatives attached the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act to its version of the National Defense Authorization Act. The SAFE Act would shield national banks from federal criminal prosecution when working with state-licensed marijuana businesses, and was widely seen as opening the door to marijuana reform. Last Tuesday, the final NDAA bill text was released without SAFE Banking Act language.

Many would say Biden has not enjoyed a legislative honeymoon, even while owning both houses of Congress. Maybe it’s only a legislative cease-fire, but whatever it is, the 11-month armistice is unlikely to hold for more than another year until Republicans retake at least one chamber. And with Americans’ perception that crime in their local area is getting worse surging over the past year, there will be less interest in criminal justice reform as the mid-terms approach.

Business Insider, Despite promises, Biden has yet to issue a single pardon, leaving reformers depressed and thousands incarcerated (December 8, 2021)

NPR, Criminal justice advocates are pressing the Biden administration for more action (December 9, 2021)

HR 6234, FIX Clemency Act (December 9, 2021)

Press Release, Bush, Pressley, Jeffries Unveil FIX Clemency Act (December 10, 2021)

Law360.com, Biden’s Inaction Keeps Justice Reform Group Sidelined (December 5, 2021)

NPR, No One Has Been Granted Clemency During Biden Administration (December 9, 2021)

Cannabis Wire, SAFE Banking Scrapped from NDAA Despite Major Push (December 8, 2021)

Gallup poll, Local Crime Deemed Worse This Year by Americans (November 10, 2021)

– Thomas L. Root

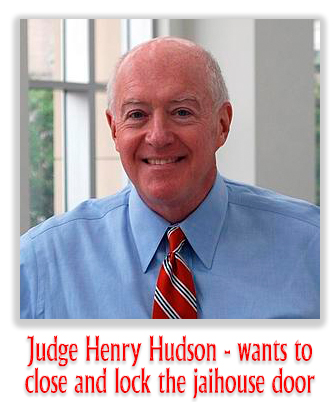

“The administration has put forth a slate that is all white, mostly male, and lacking in diverse experiences or backgrounds,” Sakira Cook, director of the justice reform program at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, told NPR. “It is critically important that the Sentencing Commission reflects the diversity of background, experience, and expertise that would make the work of the Commission most effective. It is also important to note that at least two of the candidates have records or expressed views on sentencing issues that raise serious concerns.”

“The administration has put forth a slate that is all white, mostly male, and lacking in diverse experiences or backgrounds,” Sakira Cook, director of the justice reform program at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, told NPR. “It is critically important that the Sentencing Commission reflects the diversity of background, experience, and expertise that would make the work of the Commission most effective. It is also important to note that at least two of the candidates have records or expressed views on sentencing issues that raise serious concerns.”