We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

COMPASSIONATE RELEASE STATS ALL OVER THE MAP, SENTENCING COMMISSION REPORTS

Everyone was shocked, shocked, I tell you, when the US Sentencing Commission reported last week that compassionate release since the passage of the First Step Act in December 2018 through the end of FY 2020 (September 30, 2020, has been largely a geographical crapshoot.

Everyone was shocked, shocked, I tell you, when the US Sentencing Commission reported last week that compassionate release since the passage of the First Step Act in December 2018 through the end of FY 2020 (September 30, 2020, has been largely a geographical crapshoot.

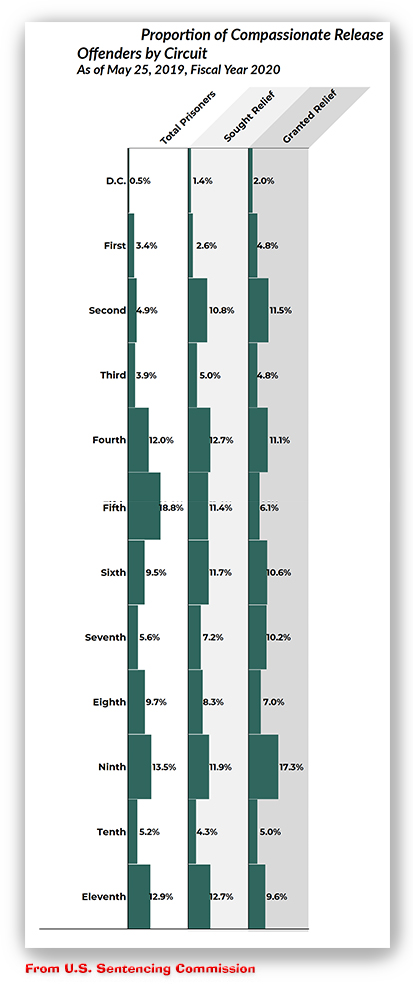

The 1st Circuit (Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Massachusetts) had the highest compassionate release grant rate at 47.5%, while the 5th Circuit (Texas, Mississippi and Louisiana) was lowest at 13.7%. Second place for compassion went to the 9th at 37.3% with honorable mention to the 7th at 36.6%. The bottom dwellers included the 11th at 19.5% and 8th at 21.3% (although in fairness, no other Circuit came close to the 5th Circuit’s dismal approval rate).

Within all of the circuits, the best places to win compassionate release were Rhode Island (25 compassionate release motions granted out of 32 filed, or 78.1%), Connecticut (49 of 68 granted, for 72.1%), and Oregon (39 of 55 granted, for 70.9%). At the other end of the scale, South Dakota (0 out of 16, for 0.0%), Western District of North Carolina (3 of 172, for 1.7%), and Southern District of West Virginia (1 out of 40, or 2.5%), were the worst places to be.

(I have excluded districts where fewer than 10 motions were filed from this: otherwise, Puerto Rico was the best place, with 8 out of 9 granted (88.9%)).

The national average for compassionate release grants during the 2-year period was 25.7%. Courts granted 1,805 requests in fiscal year 2020 and 145 requests in FY 2019.

Age, original sentence length, and the amount of time already served emerged as the central factors affecting likelihood of a compassionate release grant.

By contrast, an offender’s race, criminal history category, and offense of conviction generally appeared to have little impact on the likelihood of a compassionate release grant. Still, it is interesting that the offenses most likely to get compassionate release were immigration (50% of compassionate release motions granted), administration of justice (42% granted) and bribery/corruption (37.8%). The offenses with the worst odds were stalking/harassing (12.5%), sexual abuse (13.2%) and kidnapping (13.8%). Someone with a murder conviction was more likely to win compassionate release (19%) than one with a child pornography count (17.6%).

By contrast, an offender’s race, criminal history category, and offense of conviction generally appeared to have little impact on the likelihood of a compassionate release grant. Still, it is interesting that the offenses most likely to get compassionate release were immigration (50% of compassionate release motions granted), administration of justice (42% granted) and bribery/corruption (37.8%). The offenses with the worst odds were stalking/harassing (12.5%), sexual abuse (13.2%) and kidnapping (13.8%). Someone with a murder conviction was more likely to win compassionate release (19%) than one with a child pornography count (17.6%).

On average, prisoners granted relief had served 80 months and at least half of their sentences. The success rate was 57%for prisoners who had been sentenced to a year or less, 20% for prisoners with sentences between 120 and 240 months, and 30% for those who had been sentenced to 20 years or more. The average compassionate release sentence reduction was 59 months (42.6% of the original sentence).

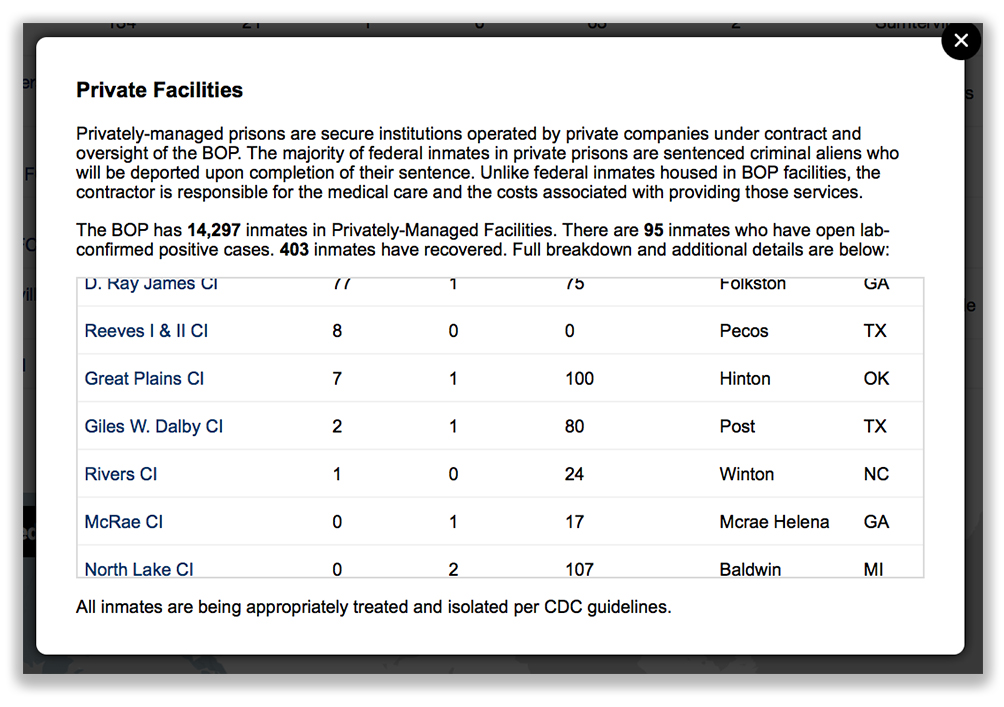

The pandemic led to a surge in motions from prisoners who worried that they might die from COVID-19 contracted in the crowded conditions of their confinement. Courts received more than 7,000 motions – 96% of which were filed by prisoners – and granted a quarter of them. Judges cited COVID-19 risks in granting compassionate release 72% of the time.

The study makes clear that how federal courts apply 18 USC 3582(c)(1)(A)(i) varies greatly, “underscoring the need to restore the U.S. Sentencing Commission,” Law360 said. “President Joe Biden, after a year in office, has yet to nominate new commissioners, keeping a potentially key player in justice reform on the sidelines.”

Individuals aged 75 or older, who make up a smaller portion of prison populations, were granted compassionate release at the highest rate — more than 60%. Courts granted compassionate release at the lowest rate — less than 20%— to people under the age of 45, according to the report. The most common reason for denying relief was failure to demonstrate an “extraordinary and compelling” reason (two-thirds of denials). Failure to exhaust administrative remedies, cited in a third of cases, was the next most common reason.

Notably, “danger to the public” was cited less than a quarter of the time, “which makes you wonder about the public safety rationale for keeping most of these prisoners behind bars,” Reason magazine said. ‘The ages of many federal prisoners cast further doubt on that rationale, since recidivism declines sharply with age.”

The number of compassionate releases in 2020 was anomalously high because of the pandemic. “After the study period ended,” the USSC notes, “the number of offenders granted compassionate release substantially decreased.” Yet the 1,805 people who were granted compassionate release in 2020 represented just 1% of the federal prison population. Congress, which sets federal penalties, and President Joe Biden, who has the power to free any prisoner whose punishment he deems unjust and promised to “broadly use” that power but has not used it at all yet, might want to consider the possibility that there is room for a bit more compassion.

Law360, Compassionate Release Grants Vary Without Advisory Board (March 10, 2022)

Reason, Compassionate Releases of Federal Prisoners Surged During the Pandemic (March 11, 2022)

US Sentencing Commission, Compassionate Release – The Impact of the First Step Act and COVID-19 Pandemic (March 10, 2022)

Reuters, Conservative U.S. judicial regions less apt to grant inmates compassionate release -commission report (March 10, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root

“The administration has put forth a slate that is all white, mostly male, and lacking in diverse experiences or backgrounds,” Sakira Cook, director of the justice reform program at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, told NPR. “It is critically important that the Sentencing Commission reflects the diversity of background, experience, and expertise that would make the work of the Commission most effective. It is also important to note that at least two of the candidates have records or expressed views on sentencing issues that raise serious concerns.”

“The administration has put forth a slate that is all white, mostly male, and lacking in diverse experiences or backgrounds,” Sakira Cook, director of the justice reform program at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, told NPR. “It is critically important that the Sentencing Commission reflects the diversity of background, experience, and expertise that would make the work of the Commission most effective. It is also important to note that at least two of the candidates have records or expressed views on sentencing issues that raise serious concerns.”