We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

NO, CAMPERS ARE NOT BEING SENT HOME (AND OTHER MYTHS)

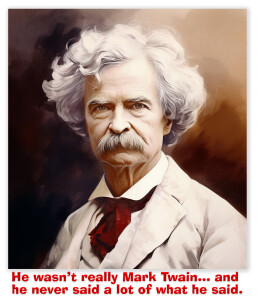

Mark Twain once said, “A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

Mark Twain once said, “A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

Oh, the sweet irony! Because it appears that Mark Twain (whose name wasn’t really “Mark Twain,” another lie) did not really say that. In other words, it’s a lie that Twain (the name itself being another lie) said that “a lie can travel half way around the world…”

Fitting for today’s post, because it’s hard to say how a lie like that can take flight. That leads us to two whoppers spreading through the Federal Bureau of Prisons like flu in a housing unit.

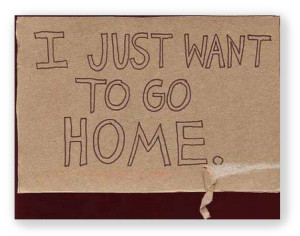

Myth 1 – All minimum-security federal inmates with fewer than five years left are being sent to home confinement. I get at least a dozen emails a week on this one: Is it true that Trump signed an executive order sending campers home? Is it true that it will all happen in September? Is it true that all the camps will close?

Myth 1 – All minimum-security federal inmates with fewer than five years left are being sent to home confinement. I get at least a dozen emails a week on this one: Is it true that Trump signed an executive order sending campers home? Is it true that it will all happen in September? Is it true that all the camps will close?

The answers are no, no, and no.

Trump has signed about 200 executive orders since January 20th, but not a one relates to the Bureau of Prisons (except the order to re-open Alcatraz). Nothing has been scheduled for September. BOP Director William K. Marshall III will not be personally driving everyone home. The camps will not close. It’s all a myth.

Here are the facts: The BOP is only allowed to send people to home confinement in one of two cases. Either the prisoner is in the last six months (or 10%, whichever’s less) of his or her sentence, or the prisoner is eligible to use FSA credits. For the former, 18 USC § 3624(c)(2) lets the prisoner go to home confinement. For the latter, 18 USC § 3624(g)(2)(A) permits spending those FSA credits on home confinement.

Congress has dictated when and how home confinement can be designated. Other Congressional home confinement programs (CARES Act and Elderly Offender Home Detention) expired two years ago. The President cannot order the BOP to send people to home confinement where Congress has passed laws expressly limiting it.

Myth 2 – Send me a copy of the new meth law: I get nearly as many emails from people asking me to send them a copy of the “new meth law.” Do I look like a lending library? No matter, the response is straightforward. There is no new meth law.

Myth 2 – Send me a copy of the new meth law: I get nearly as many emails from people asking me to send them a copy of the “new meth law.” Do I look like a lending library? No matter, the response is straightforward. There is no new meth law.

In January, the Sentencing Commission said it was considering a change in the methamphetamine guidelines to do away with the purity enhancement, an increase in punishment where the meth was especially pure (or was “ice”). The change made great sense: these days, virtually all meth met the higher purity threshold, and so the old supposition – that very pure meth suggested the defendant was a high-level dealer – no longer had any legs.

In April, the USSC adopted proposed amendments that will take effect in November. The meth purity proposal was not among them. To this day, no one knows what happened to the idea.

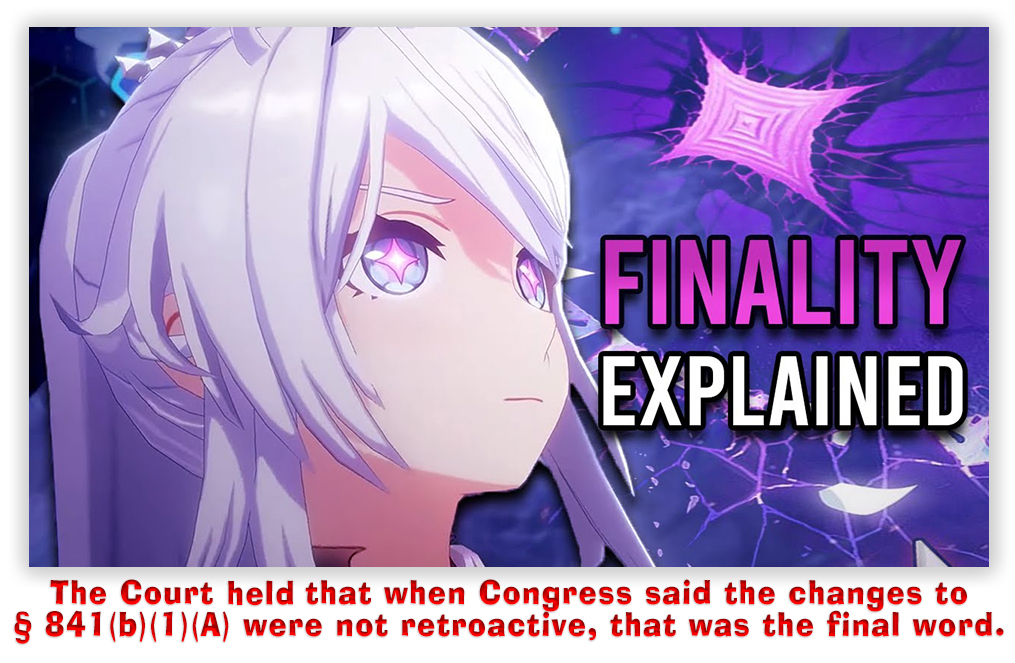

A few points: First, a Guideline is not a law. Judges must follow laws but not guidelines. Laws can be passed that trample guidelines, but guidelines cannot negate laws. Second, the drug trafficking sentence statute (21 USC § 841(b)) contains enhanced penalties for pure meth, and any guidelines change would not change the law and therefore have limited effect. Third, no one in the Republican majority Congress has any interest in easing the drug laws right now, even if fentanyl is the drug bad-boy-of-choice right now.

A few points: First, a Guideline is not a law. Judges must follow laws but not guidelines. Laws can be passed that trample guidelines, but guidelines cannot negate laws. Second, the drug trafficking sentence statute (21 USC § 841(b)) contains enhanced penalties for pure meth, and any guidelines change would not change the law and therefore have limited effect. Third, no one in the Republican majority Congress has any interest in easing the drug laws right now, even if fentanyl is the drug bad-boy-of-choice right now.

Recap: Home confinement for campers is a fantasy. A new meth law is a myth. And Mark Twain was not Mark Twain, and he probably never said most of the things he said.

– Thomas L. Root