We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WELCOME BACK, RECIDIVISTS!

There has been little in compassionate release litigation that has been more disappointing (and intellectually dishonest) than the government’s ratchet-like arguments about the danger that the prisoner seeking a sentence reduction poses to the public if he or she gains a release earlier than the expiration of the original sentence.

There has been little in compassionate release litigation that has been more disappointing (and intellectually dishonest) than the government’s ratchet-like arguments about the danger that the prisoner seeking a sentence reduction poses to the public if he or she gains a release earlier than the expiration of the original sentence.

The Dept of Justice PATTERN system provides a metric comparing an inmate’s likelihood of general recidivism and violent crime recidivism to the universe of federal prisoners by rating the inmate in 15 categories. The resulting ratings place an inmate in categories of minimum, low, medium or high risk of recidivism.

PATTERN was adopted to work hand-in-glove with the recidivism reduction program adopted in the First Step Act. A prisoner could, through good conduct and successful completion of programs designed to decrease recidivism, lower his or her recidivism level and benefit from the rewards of good programming, time reduction of up to a year and early placement in halfway house or home confinement.

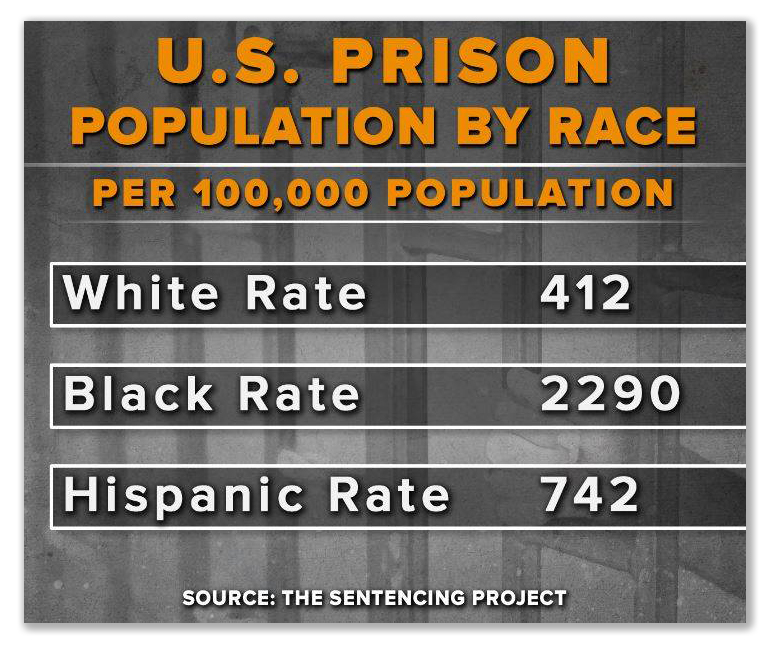

DOJ officially has a fan of PATTERN, saying that it has “confidence in the accuracy of PATTERN,” a system that uses “many factors that are scientifically-weighted based on their predictability of reduced recidivism… factors most predictive of the risk of recidivism… The Department [has] measured PATTERN to ensure that it was predictive across all races and genders.”

At least, it’s been a fan except where fandom is inconvenient. Where an inmate’s risk of recidivism is “medium” or “high,” you can depend on the government to argue to the court that the risk to the public of early release is too elevated to justify compassionate release. But when a prisoner’s recidivism risk is “low” or “minimum,” you can usually count on the US Attorney to argue that despite the rating, grant of compassionate release will endanger the public anyway.

Heads, I win. Tails, you lose.

Heads, I win. Tails, you lose.

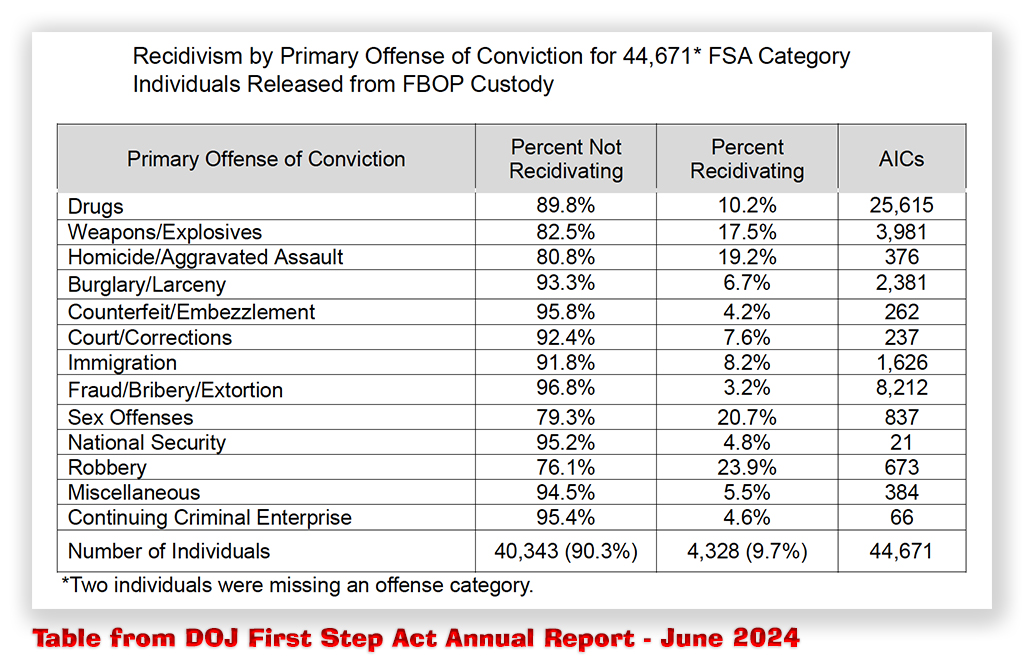

Up to now, a prisoner’s risk to the public has been an easy issue for the government to demagogue. An FSA-eligible prisoner seeking to convince a court that the DOJ’s own rating is reliable facing a dearth of real-world data to cite. However, the DOJ’s First Step Act Annual Report – June 2024 contains ample recidivism data that underscores the likelihood that PATTERN has it right.

People with minimum PATTERN recidivism ratings reoffend at the rate of 2.8%. People with low ratings reoffend at the rate of 5.6%. The medium-rating folks commit new crimes at the rate of 21.9%, while the high-rating people top the charts at 38.2%.

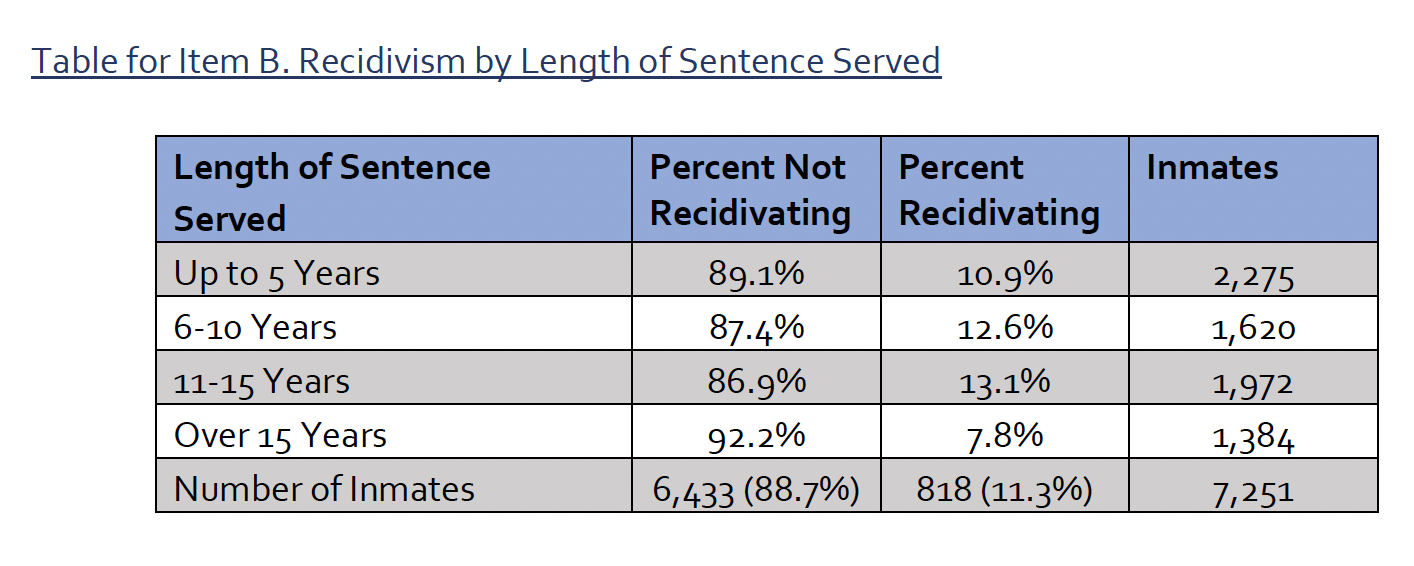

What is surprising is that sentence length appears to be largely untethered from recidivism. People serving five years or less reoffend at the rate of 7%. Those who do 6-10 years recidivate at the rate of 10.5%, while those serving 11-15 years have a reoffense level within three years of 20.4%. Only people who have done more than 15 years reverse the trend, with a recidivism rate of 15.6%.

Still, these reoffense rates undermine the conventional wisdom that longer sentences are effective in curbing recidivism.

Protection of the public, one of the sentencing factors listed in 18 USC § 3553(a), is undoubtedly an important element of corrections policy. The First Step requirement that the BOP keep track of its FSA “graduates” makes an important contribution to addressing the issue with fact instead of hyperbole.

Protection of the public, one of the sentencing factors listed in 18 USC § 3553(a), is undoubtedly an important element of corrections policy. The First Step requirement that the BOP keep track of its FSA “graduates” makes an important contribution to addressing the issue with fact instead of hyperbole.

Dept of Justice, First Step Act Annual Report – June 2024

Dept of Justice, The First Step Act of 2018: Risk and Needs Assessment System (July 19, 2019)

Dept of Justice, The First Step Act of 2018: Risk and Needs Assessment System Update – January 2020 (January 15, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

Writing in

Writing in