We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

JUDGE SAYS “DISGUSTING, INHUMAN” BOP NYC FACILITIES ARE RUN BY MORONS

A senior Federal judge who navigated her Manhattan-based court through the pandemic denounced conditions at MDC Brooklyn and MCC New York as “disgusting” and “inhuman” during the sentencing last month of a woman who spent months in solitary confinement after contracting COVID-19.

A senior Federal judge who navigated her Manhattan-based court through the pandemic denounced conditions at MDC Brooklyn and MCC New York as “disgusting” and “inhuman” during the sentencing last month of a woman who spent months in solitary confinement after contracting COVID-19.

US District Court Judge Colleen McMahon said in a transcript just obtained by the Washington Post that the facilities are “run by morons.” During the sentencing, McMahon castigated the BOP, saying the agency’s ineptitude and failure to “do anything meaningful” at the MCC in Manhattan and MDC Brooklyn amounted to the “single thing in the five years that I was chief judge of this court that made me the craziest.”

“It is the finding of this court that the conditions to which the defendant was subjected are as disgusting, inhuman as anything I’ve heard about any Colombian prison,” McMahon said on the record, “but more so because we’re supposed to be better than that.”

The BOP responded in a statement that it “takes seriously our duty to protect the individuals entrusted in our custody, as well as maintain the safety of correctional staff and the community.”

Meanwhile, The Trentonian reported last week that FCI Fort Dix set as COVID-19 record for the worst outbreaks of any federal facility. New Jersey US Senators Bob Menendez and Cory Booker, both Democrats, called on the BOP last month to “prioritize the vaccination program” at FCI Fort Dix. More than 70% of the 2,800 prisoners at Fort Dix have tested positive for COVID-19 since the pandemic began. As of last week, 52% of Fort Dix inmates have been vaccinated.

Meanwhile, The Trentonian reported last week that FCI Fort Dix set as COVID-19 record for the worst outbreaks of any federal facility. New Jersey US Senators Bob Menendez and Cory Booker, both Democrats, called on the BOP last month to “prioritize the vaccination program” at FCI Fort Dix. More than 70% of the 2,800 prisoners at Fort Dix have tested positive for COVID-19 since the pandemic began. As of last week, 52% of Fort Dix inmates have been vaccinated.

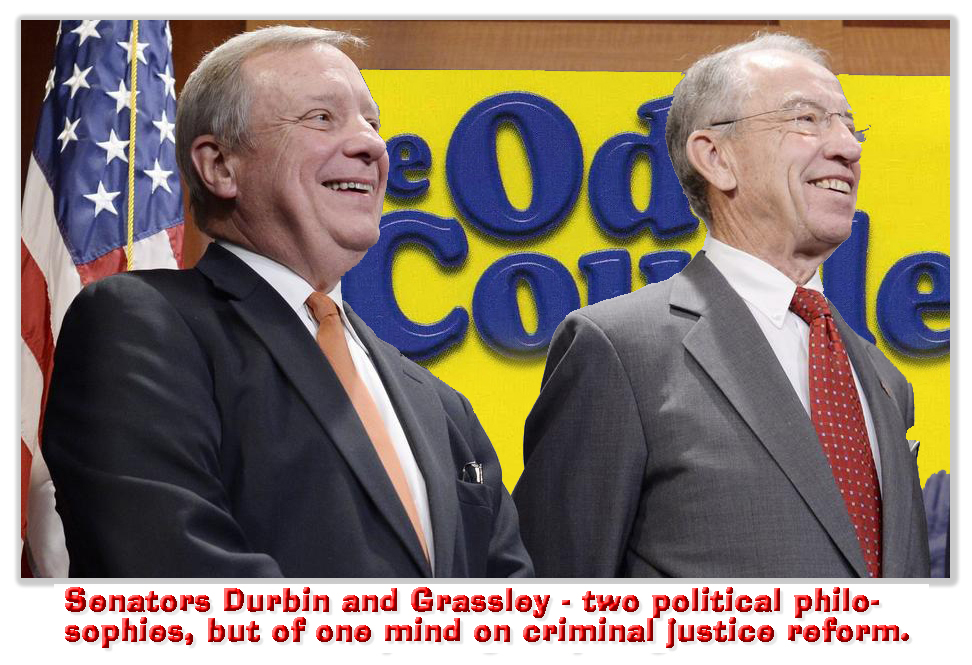

Also last week, the Legislative Committee of the Federal Public and Community Defenders wrote a 16-page letter to Senate Judiciary Chairman Richard Durbin (D-Illinois) and Ranking Member Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) asking for Congressional action to reform the BOP in areas as varied as inmate healthcare to compassionate release to First Step Act programming credits.

“Although the Biden Administration has taken significant steps to beat back COVID-19 in the community,” the letter said, “individuals in BOP custody remain at high risk. Over a year into the pandemic, they are subject to harsh and restrictive conditions of confinement and lack adequate access to medical care, mental health services, and programming. The improvements to programming promised by the First Step Act generally stand unfulfilled.”

Most significant was criticism of BOP healthcare that went beyond the pandemic: “Dr. Homer Venters, a physician and epidemiologist who has inspected several BOP facilities to assess their COVID-19 response, identified a “disturbing lack of access to care when a new medical problem is encountered” and is concerned that “[w]ithout a fundamental shift in how BOP approaches… health services, people in BOP custody will continue to suffer from preventable illness and death, including the inevitable and subsequent infectious disease outbreaks.”

The letter also took aim at the high vaccine refusal rate by BOP staff (currently 50.5% refused), staffing shortages, and the BOP’s poor record on granting compassionate release.

The letter also took aim at the high vaccine refusal rate by BOP staff (currently 50.5% refused), staffing shortages, and the BOP’s poor record on granting compassionate release.

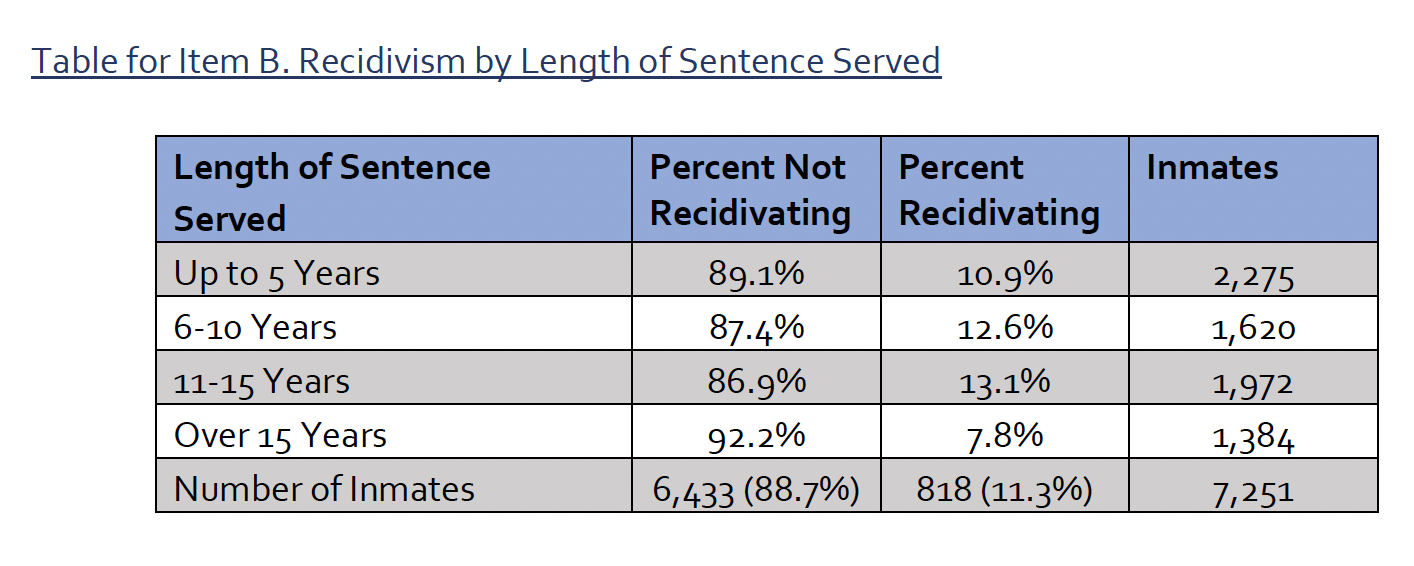

The letter complains that the BOP’s proposed rule on awarding earned time credit “impermissibly restricts an individual’s ability to earn time credits, makes it too easy to lose those credits, and unduly excludes broad categories from the earned time credit system. In short, these provisions kneecap the FSA’s incentive structure and make it less likely individuals will participate in programs and activities to reduce recidivism and increase public safety.” The letter notes that if a prisoner programmed 40 hours a week, it would take more time to earn a year’s credit than the length of the average federal sentence.

The Trentonian, Ft Dix FCI has largest total COVID-19 cases among U.S. federal prisons (May 4, 2021)

Federal Public and Community Defenders, Letter to Sens Durbin and Grassley (May 4, 2021)

Washington Post, Judge says ‘morons’ run New York’s federal jails, denounces ‘inhuman’ conditions (May 7, 2021)

– Thomas L. Root

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a