We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

TERRY V. UNITED STATES: ‘OH, THAT’S BAD! NO, THAT’S GOOD…’

If you remember Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, you probably have a Medicare card in your wallet. After “Wooly Bully,” Sam and band – traveling around in a 1952 packard hearse – recorded a few other hits, the last of which was the rather confusing 1973 balled “Oh That’s Good, No That’s Bad.”

The plot – such as it is – had Sam describing a series of events in his love life, each one sounding either like a victory that was actually a defeat or a defeat that was actually a victory. Such could be the story of this week’s Supreme Court decision in Terry v. United States, in which the petitioner – sentenced for a crack offense prior to the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act – argued that his 21 USC 841(b))(1)(C) sentence was covered by Section 404 of the First Step Act, and that he was thus entitled to be resentenced.

The plot – such as it is – had Sam describing a series of events in his love life, each one sounding either like a victory that was actually a defeat or a defeat that was actually a victory. Such could be the story of this week’s Supreme Court decision in Terry v. United States, in which the petitioner – sentenced for a crack offense prior to the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act – argued that his 21 USC 841(b))(1)(C) sentence was covered by Section 404 of the First Step Act, and that he was thus entitled to be resentenced.

A quick review: drug sentences are imposed under 21 USC 841(b)(1). The worst sentences – based on quantity of drugs involved – are imposed by § 841(b)(1)(A). Lesser quantities are punished by § 841(b)(1)(B). If the indictment does not specify any minimum quantity of drugs sold, the sentence is imposed by § 841(b)(1)(C). Not surprisingly, the (b)(1)(A) sentences are the harshest, starting at a mandatory minimum of 10 years and increasing based on the number of prior drug and violent crimes committed or other factors (such as if a drug user died from drugs you provided).

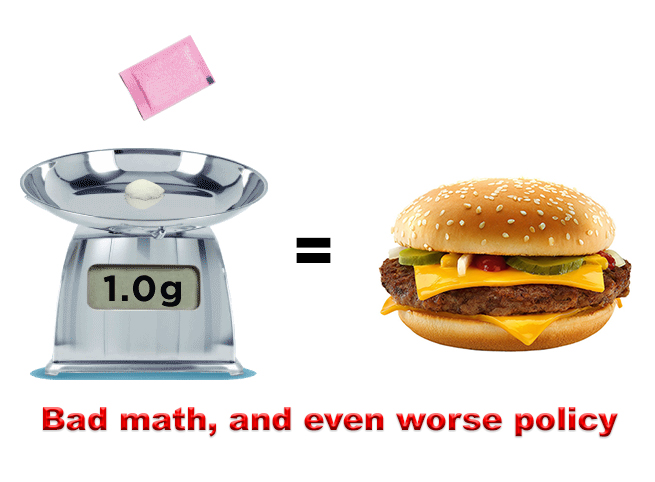

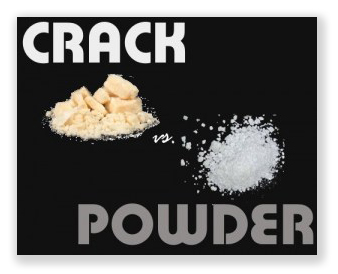

Before 2010, crack cocaine was assessed for sentencing purposes at 100 times the weight of powder. That meant that 10 grams of crack (about two teaspoons) was sentenced as if it were 2.2 lbs (a kilo) of powder cocaine. The ratio was Congress’s knee-jerk reaction to the early 90s belief that crack was a powerful scourge destroying our inner cities. Of course, the fact that it was mostly sold in the inner cities led to most of the defendants who were hammered by incredibly long sentences were black.

The Fair Sentencing Act recognized the disparate impact of the 100:1 ratio by reducing it to a mere 18:1 (proponents wanted a 1:1 ratio, but compromised to gain enough Senate support for passage). The FSA modified the amounts of crack needed to trigger the mandatory minimums in § 841(b)(1)(A) and (b)(1)(B) accordingly. Where a mere 5 grams (one teaspoon) of crack would buy a defendant a minimum five years, now that mandatory sentence required 28 grams. The prior 50-gram minimum for a (b)(1)(A) sentence became 280 grams.

At the same time, the FSA was made to be prospective only (not retroactive) to secure enough Republican votes to pass.

Eight years later, First Step § 404 corrected the non-retroactivity, making anyone who, before August 2010, had “a violation of a Federal criminal statute, the statutory penalties for which were modified by section 2 or 3 of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.” As of last month, over 3,700 prisoners have won reduced sentences from application of First Step § 404.

That brings us to the strange case of Taharick Terry. in 2008, Tarahrick, then in his early 20s, was arrested in Florida for carrying just under 4 grams of crack cocaine. He was sentenced under 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(C), which carried no mandatory minimum, because the crack he possessed didn’t make the then-applicable § (b)(1)(B) 5-year mandatory minimum. But while he had no statutory minimum, he did have enough priors to qualify as a “career offender” under the Sentencing Guidelines. As a “career offender,” Taharick was hammered with a maximum Criminal History Category and offense level, yielding a 188-month sentence.

That brings us to the strange case of Taharick Terry. in 2008, Tarahrick, then in his early 20s, was arrested in Florida for carrying just under 4 grams of crack cocaine. He was sentenced under 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(C), which carried no mandatory minimum, because the crack he possessed didn’t make the then-applicable § (b)(1)(B) 5-year mandatory minimum. But while he had no statutory minimum, he did have enough priors to qualify as a “career offender” under the Sentencing Guidelines. As a “career offender,” Taharick was hammered with a maximum Criminal History Category and offense level, yielding a 188-month sentence.

Taharick applied for § 404 relief, but his district judge turned him down. Taharick’s offense did not carry a “statutory penalt[y] which were modified by section 2 or 3 of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.” Before the FSA, the mandatory minimum for a § (b)(1)(C) was zero. After the FSA, it remained zero. Therefore, the district court ruled, Taharick was not entitled to use § 404 for resentencing.

Just as briefs on Terry were due in the Supreme Court last March, the Biden Justice Department surprised the Supreme Court by announcing that it would no longer defend the district court’s holding that Taharick could not get resentenced under § 404. The Supremes had to scramble, quickly appointing a private lawyer to argue the government’s former position. Dozens of amicus briefs arguing for Taharick’s relief – including one by Senators Richard Durbin, Charles Grassley, Cory Booker, and Mike Lee – opposed the district court’s narrow reading of the statute.

Just as briefs on Terry were due in the Supreme Court last March, the Biden Justice Department surprised the Supreme Court by announcing that it would no longer defend the district court’s holding that Taharick could not get resentenced under § 404. The Supremes had to scramble, quickly appointing a private lawyer to argue the government’s former position. Dozens of amicus briefs arguing for Taharick’s relief – including one by Senators Richard Durbin, Charles Grassley, Cory Booker, and Mike Lee – opposed the district court’s narrow reading of the statute.

Sam the Sham might have crooned, “Oh, that’s good!” After all of that, how could Taharick possibly lose?

This is how: Earlier this week, the Supremes ruled 9-0 that the statute says what it says. The Court held that the language under which Taharick was sentenced was not modified by the sentencing-reform statutes. Although the change to levels above (b)(1)(C) would suggest that the punishment of lower amounts of drugs should also be read differently, the low-level provisions were not “modified.” The district court read it exactly the way Congress wrote it. And that was that.

Sam might croon, “Oh, that’s bad.”

But the decision was fascinating because of the Justices’ dueling histories of the law. Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote the opinion, presented one that noted how even Black leaders were in favor of harsh crack laws when the 100:1 ratio was enacted. Concurring Justice Sonia Sotomayor focused more on the unfulfilled social-program support that was to be the carrot that came with the 100:1 stick.

Justices arguing racial justice? “Oh, that’s good.”

If you believe popular media coverage of the Terry decision – which I think was preordained by a common-sense reading of § 404 – you would conclude that the decision was a social disaster wrought by racist Justices. “Supreme Court ruling on crack sentences ‘a shocking loss,’ drug reform advocates say,” NBC howled. “SCOTUS deals a gutting blow to federal criminal justice reform,” The Week moaned. Even Reuters signaled its disapproval that the chary Supreme Court did not elect to help out defendants (as though it were a legislature and not a court): “U.S. Supreme Court declines to expand crack cocaine reforms.”

If you believe popular media coverage of the Terry decision – which I think was preordained by a common-sense reading of § 404 – you would conclude that the decision was a social disaster wrought by racist Justices. “Supreme Court ruling on crack sentences ‘a shocking loss,’ drug reform advocates say,” NBC howled. “SCOTUS deals a gutting blow to federal criminal justice reform,” The Week moaned. Even Reuters signaled its disapproval that the chary Supreme Court did not elect to help out defendants (as though it were a legislature and not a court): “U.S. Supreme Court declines to expand crack cocaine reforms.”

But the Terry decision’s unanimity suggests that nonpartisan judging rather than motivated interpretations underlay the decision. If Congress meant to reach (b)(1)(C) cases, it should say what it means. It did not do so. Lousy draftsmanship? Perhaps just the rush to get First Step passed in the final hours of the 115th Congress? Those were hectic times. The logical inference is that Congress failed. And that’s bad.

But maybe the Terry decision’s good. Already, commentators are arguing that Terry should spur Congress to get down to passing significant criminal justice reform. The Supremes handed the Biden Administration a “humiliating loss” after the DOJ’s 11th-hour flip-flop. Sens. Durbin and Grassley cannot be happy that their position was summarily rejected. Reps. Cori Bush (D-Mo.) and Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-N.J.) announced this week that they will introduce the Drug Policy Reform Act, which would decriminalize all drugs, expunge existing records and allow for re-sentencing, and invest in health-centered measures to take on drug addiction.

If Taharick Terry had won, the victory would have little impact. He gets out of prison in three months anyway. Most (b)(1)(C) crack cases from before 2010 benefitted from two 2-level retroactive reductions approved by the Sentencing Commission in 2011 and 2014. Most (b)(1)(C) defendants – even career offenders like Taharick, who could not get any 2-level reduction – have completed their sentences by now. And Terry would have had no effect on any sentences imposed after August 2010.

If Taharick Terry had won, the victory would have little impact. He gets out of prison in three months anyway. Most (b)(1)(C) crack cases from before 2010 benefitted from two 2-level retroactive reductions approved by the Sentencing Commission in 2011 and 2014. Most (b)(1)(C) defendants – even career offenders like Taharick, who could not get any 2-level reduction – have completed their sentences by now. And Terry would have had no effect on any sentences imposed after August 2010.

But the Terry loss – in an era of racial justice reckoning – is coming to be seen as a wake-up call for Congress to get serious on criminal justice reform. The Supreme Court will not clean up the mess Congress made in the drug war. It will not clean up poorly-drafted First Step language. That’s up to Congress, and maybe now, Congress knows it.

“Oh, that’s good.”

Terry v United States, Case No. 20-5904, 2021 U.S. LEXIS 3111 (June 14, 2021)

US Sentencing Commission, First Step Act of 2018 Resentencing Provisions Retroactivity Data Report (May 2021)

NBC, Supreme Court ruling on crack sentences ‘a shocking loss,’ drug reform advocates say (June 15)

The Week, SCOTUS deals a gutting blow to federal criminal justice reform (June 14)

Reuters, U.S. Supreme Court declines to expand crack cocaine reforms (June 14)

– Thomas L. Root

We reported last Friday on the House passage of the EQUAL Act. In our glee over the potential redress of the racially disparate crack-to-powder laws, we overlooked the House Judiciary Committee’s approval of the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, H.R. 3617, on a 26-15 vote.

We reported last Friday on the House passage of the EQUAL Act. In our glee over the potential redress of the racially disparate crack-to-powder laws, we overlooked the House Judiciary Committee’s approval of the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, H.R. 3617, on a 26-15 vote. Meanwhile, Sen. Richard Durbin (D-IL), Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), and others last week introduced the Terry Technical Correction Act, which clarifies that individuals convicted of the lowest level crack offenses before the Fair Sentencing Act passed can apply for its retroactive application under Section 404 of the First Step Act. The same bill was introduced simultaneously in the House by bipartisan cosponsors led by Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) and Rep. Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-TX).

Meanwhile, Sen. Richard Durbin (D-IL), Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA), and others last week introduced the Terry Technical Correction Act, which clarifies that individuals convicted of the lowest level crack offenses before the Fair Sentencing Act passed can apply for its retroactive application under Section 404 of the First Step Act. The same bill was introduced simultaneously in the House by bipartisan cosponsors led by Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) and Rep. Sheila Jackson-Lee (D-TX).