We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

EN BANC 9TH CIRCUIT DECISION FINDS § 922(g)(1) IS CONSTITUTIONAL

The question that has loomed for thousands of federal defendants since of the Supreme Court upended decades of 2nd Amendment jurisprudence with the 2022 New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen decision is whether 18 USC § 922(g)(1), which essentially slaps a lifetime gun possession ban on anyone with a felony conviction, remains constitutional. Second Amendment compliance of the so-called felon-in-possession statute just got more complicated, if not fractured, with last Friday’s 9th Circuit ruling in United States v. Duarte.

No one familiar with the 9th Circuit’s legendary anti-gun predisposition should be surprised.

No one familiar with the 9th Circuit’s legendary anti-gun predisposition should be surprised.

Steven Duarte got pulled over in 2019 while having a gun in his car. Because he had been convicted of five prior felonies – including vandalism, evading a cop twice, possession of drugs, and a state-law felony for possessing a gun as a felon – he was charged and convicted of an 18 USC § 922(g)(1) offense. He challenged § 922(g)(1)’s constitutionality as applied to him, and a year ago, a three-judge 9th Circuit panel ruled 2-1 that after Bruen, § 922(g)(1) was unconstitutional as applied to Steve, a nonviolent felon.

The 9th Circuit, being the 9th Circuit, voted to rehear the case en banc. Last Friday, a year to the day after the 3-judge panel ruled in Steve’s favor, the en banc court (with five judges disagreeing for one reason or another) held in a 127-page opinion that the history and tradition of gun laws in America meant that § 922(g)(1) could disarm all felons consistent with the 2nd Amendment.

Back in 2008, the Supreme Court held in District of Columbia v. Heller that the 2nd Amendment conferred “an individual right to keep and bear arms” on the people. In a frenzy of obiter dicta, the Court noted, however, that “[l]ike most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited:”

Although we do not undertake an exhaustive historical analysis today of the full scope of the Second Amendment, nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.

Two years after Heller, the Supremes repeated in McDonald v. City of Chicago that the “assurances” that Heller “did not cast doubt on such longstanding regulatory measures as ‘prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill.'”

The Duarte majority ran with that. Before Bruen, the 9th held in United States v. Vongxay that “[n]othing in Heller can be read legitimately to cast doubt on the constitutionality of § 922(g)(1)” and that “felons are categorically different from the individuals who have a fundamental right to bear arms.” The en banc majority ruled last week that “Bruen did not change or alter this aspect of Heller or McDonald. Rather, Bruen and its lineal descendent, United States v. Rahimi, support Vongxay’s holding that § 922(g)(1) constitutionally prohibits the possession of firearms by felons.

The Duarte majority ran with that. Before Bruen, the 9th held in United States v. Vongxay that “[n]othing in Heller can be read legitimately to cast doubt on the constitutionality of § 922(g)(1)” and that “felons are categorically different from the individuals who have a fundamental right to bear arms.” The en banc majority ruled last week that “Bruen did not change or alter this aspect of Heller or McDonald. Rather, Bruen and its lineal descendent, United States v. Rahimi, support Vongxay’s holding that § 922(g)(1) constitutionally prohibits the possession of firearms by felons.

First, the Bruen Court largely derived its constitutional test from Heller and stated that its analysis was consistent with Heller. Second, the Circuit said, “Bruen limited the scope of its opinion to ‘law-abiding citizens,’ evidenced by its use of the term fourteen times throughout the opinion.” The opinion lets the idea that people who have been convicted of a felony at any time in their lives can never be law-abiding citizens be inferred by the reader.

Third, the en banc 9th said, in the Bruen decision “six justices, including three in the majority, emphasized that Bruen did not disturb the limiting principles in Heller and McDonald. Finally, the Duarte ruling said, “the Bruen majority clarified that ‘nothing in our analysis should be interpreted to suggest the unconstitutionality of the 43 States’ ‘shall-issue’ licensing regimes… Justifying this reservation, the Supreme Court explained that “shall issue” laws require background checks for the very purpose of ensuring that licenses are not issued to felons.”

Following that, the Duarte court decided that because capital punishment was the penalty for many if not most felonies in colonial America and because being dead was a worse outcome than not being allowed to have a gun, permanent disarmament is consistent with everyone’s expectations at the time the 2nd Amendment was ratified. A dissenting judge referred to this as “the cold, dead fingers’ rationale.

Following that, the Duarte court decided that because capital punishment was the penalty for many if not most felonies in colonial America and because being dead was a worse outcome than not being allowed to have a gun, permanent disarmament is consistent with everyone’s expectations at the time the 2nd Amendment was ratified. A dissenting judge referred to this as “the cold, dead fingers’ rationale.

Dissenting, Judge Lawrence VanDyke argued that given the “paradigm change in Second Amendment jurisprudence that Bruen effected,” the majority’s conclusion that the Circuit’s pre-Bruen precedent remained good law. More importantly, he recognized that the effect of the majority’s holding was to give state legislatures “unilateral discretion to disarm anyone by assigning the label ‘felon’ to whatever conduct they desire” and thus “can disarm entire classes of individuals, even absent a specific showing of individual dangerousness or propensity to violence.”

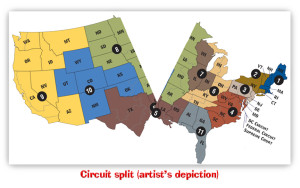

The 127-page opinion aligns the 9th Circuit with four other circuits upholding the categorical application of § 922(g)(1) to all felons, the 4th, the 8th, the 10th, and 11th. Two circuits – the 5th and 6th – have rejected “as applied” challenges like Steve’s, but have left open the possibility that § 922(g)(1) might be unconstitutional as applied to at least some felons. The 3rd Circuit has held in an en banc decision that § 922(g)(1) is unconstitutional as applied to a defendant who was convicted of making a false statement to secure food stamps (not precisely a felony, but falling within the class of prohibited people defined by § 922(g)(1)). The 1st, 2nd and 7th Circuits have thus far declined to address constitutional challenges to § 922(g)(1) on the merits.

The 127-page opinion aligns the 9th Circuit with four other circuits upholding the categorical application of § 922(g)(1) to all felons, the 4th, the 8th, the 10th, and 11th. Two circuits – the 5th and 6th – have rejected “as applied” challenges like Steve’s, but have left open the possibility that § 922(g)(1) might be unconstitutional as applied to at least some felons. The 3rd Circuit has held in an en banc decision that § 922(g)(1) is unconstitutional as applied to a defendant who was convicted of making a false statement to secure food stamps (not precisely a felony, but falling within the class of prohibited people defined by § 922(g)(1)). The 1st, 2nd and 7th Circuits have thus far declined to address constitutional challenges to § 922(g)(1) on the merits.

Writing in his Sentencing Law and Policy blog, Ohio State University law professor Doug Berman observed that

[t]he Supreme Court has so far dodged this issue, which has been broadly litigated since Heller was decided back in 2008 and which has generated considerably more lower court division since Bruen and Rahimi reoriented Second Amendment jurisprudence. With this latest ruling in the largest circuit, and with the Justice Department’s new efforts to restore gun rights to more persons with criminal convictions… I suspect the Justices might see even more reasons to avoid taking up this issue in the days ahead.

United States v. Duarte, No. 22-50048, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 11255, at *66-67 (9th Cir. May 9, 2025)

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1 (2022)

District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008)

McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010)

United States v. Rahimi, 602 U.S. 680 (2024)

United States v. Vongxay, 594 F.3d 1111 (2010)

Sentencing Law and Policy, En banc Ninth Circuit broadly rejects Second Amendment challenge to federal felon-in-possession prohibition (May 10, 2025)

– Thomas L. Root