We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

PROCEDURAL BOOTSTRAPPING

Back to the Well Once Too Often: Federal prisoners who lose their 28 USC § 2255 motions sometimes resort to filing motions to set aside the § 2255 judgment under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b), as a clever means of getting around seeking permission for a second or successive § 2255 under 28 USC § 2244. It seldom works.

Back to the Well Once Too Often: Federal prisoners who lose their 28 USC § 2255 motions sometimes resort to filing motions to set aside the § 2255 judgment under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b), as a clever means of getting around seeking permission for a second or successive § 2255 under 28 USC § 2244. It seldom works.

A few fun facts: First, although a post-conviction motion under 28 USC § 2255 challenges a criminal conviction or sentence, the § 2255 proceeding itself is considered to be a civil action. That is how a movant even has the option to employ Fed.R.Civ.P. 60(b), or any other Federal Rule of Civil Procedure, for that matter. Second, Rule 60(b) – which governs motions to set aside the judgment – is usable after a final judgment is rendered, although that some time constraints and designated bases for invoking the Rule that are beyond today’s discussion. Third, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act – known as the AEDPA – puts severe restrictions on prisoners bringing more than a single § 2255 motion without meeting some pretty high standards (a new retroactive rule of constitutional law or some killer new evidence) and getting advance approval from a United States Court of Appeals under 28 USC § 2244. These restrictions can run headlong into a Rule 60(b) motion.

Desmond Rouse and several co-defendants were convicted based on what they called “outdated, false, misleading, and inaccurate” forensic medical evidence, testimony that had since been recanted, and juror racism. Having failed to win their § 2255 motions, they filed a motion to set aside the § 2255 judgment under Rule 60(b), arguing that a “new rule” announced in Peña-Rodriguez v Colorado would now let them “investigate whether their convictions were based upon overt [juror] racism,” and the witness recantations showed they were actually innocent.

Last week, the 8th Circuit rejected the Rule 60(b) motion as a second-or-successive § 2255 motion.

The Circuit held that newly discovered evidence in support of a claim previously denied and a subsequent change in substantive law “fall squarely within the class of Rule 60(b) claims to which the Supreme Court applied § 2244(b) restrictions in Gonzalez v. Crosby back in 2005. The requirement in § 2244(b)(3) that courts of appeals first certify compliance with § 2244(b)(2) before a district court can accept a motion for second or successive relief applies to Rule 60(b)(6) motions that include second or successive claims. Our prior denial of authorization did not sanction Appellants’ repackaging of their claims in Rule 60(b)(6) motions to the district court. The motions are improper attempts to circumvent the procedural requirements of AEDPA.”

The Circuit held that newly discovered evidence in support of a claim previously denied and a subsequent change in substantive law “fall squarely within the class of Rule 60(b) claims to which the Supreme Court applied § 2244(b) restrictions in Gonzalez v. Crosby back in 2005. The requirement in § 2244(b)(3) that courts of appeals first certify compliance with § 2244(b)(2) before a district court can accept a motion for second or successive relief applies to Rule 60(b)(6) motions that include second or successive claims. Our prior denial of authorization did not sanction Appellants’ repackaging of their claims in Rule 60(b)(6) motions to the district court. The motions are improper attempts to circumvent the procedural requirements of AEDPA.”

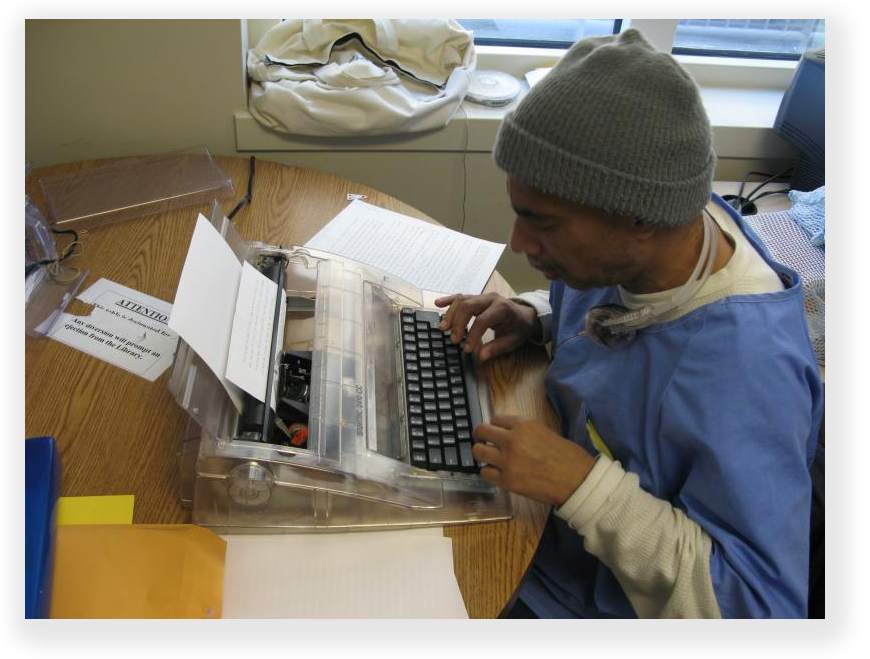

Back to the Well is Just Fine: In the 7th Circuit, however, a prisoner who filed reconsideration on denial of his First Step Act Section 404 motion chalked up a procedural win. Within the 14 days allowed for filing a notice of appeal after his district court denied him a sentence reduction, William Hible filed a motion asking the district judge to reconsider his denial. The judge denied the motion, and Bill filed his notice of appeal, again within 14 days of the denial. The government argued the notice was late, because a motion for reconsideration doesn’t stop the appeal deadline from running.

Last week, the 7th Circuit agreed with Bill. The 7th observed that while the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure lack any parallel to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 59, the Supreme Court “has held repeatedly that motions to reconsider in criminal cases extend the time for appeal. But under the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, only Criminal Rules 35 and 36 offer any prospect of modification by the district judge. Rule 36 is limited to the correction of clerical errors. Under Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 4(b)(5), a motion under Rule 35 does not affect the time for appeal.

The government argued these rules govern sentence reduction proceedings, but the 7th disagreed. The Circuit said the First Step Act authorizes reduction of a sentence long after the time allowed by Rule 35. Thus, “the First Step Act’s authorization to reduce a prisoner’s sentence is external to Rule 35,” so the provision in Rule 4(b)(5) about the effect of Rule 35 motions does not apply here. A reconsideration motion in a 404 proceeding thus stops the running of the time to appeal, and Hible’s notice of appeal was timely.

The government argued these rules govern sentence reduction proceedings, but the 7th disagreed. The Circuit said the First Step Act authorizes reduction of a sentence long after the time allowed by Rule 35. Thus, “the First Step Act’s authorization to reduce a prisoner’s sentence is external to Rule 35,” so the provision in Rule 4(b)(5) about the effect of Rule 35 motions does not apply here. A reconsideration motion in a 404 proceeding thus stops the running of the time to appeal, and Hible’s notice of appeal was timely.

Rouse v. United States, Case No. 20-2007, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 27795 (8th Cir., September 16, 2021)

United States v. Hible, Case No. 20-1824, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 27548 (7th Cir., September 14, 2021)

– Thomas L. Root