We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE LAST JOHNSON DOMINO FALLS

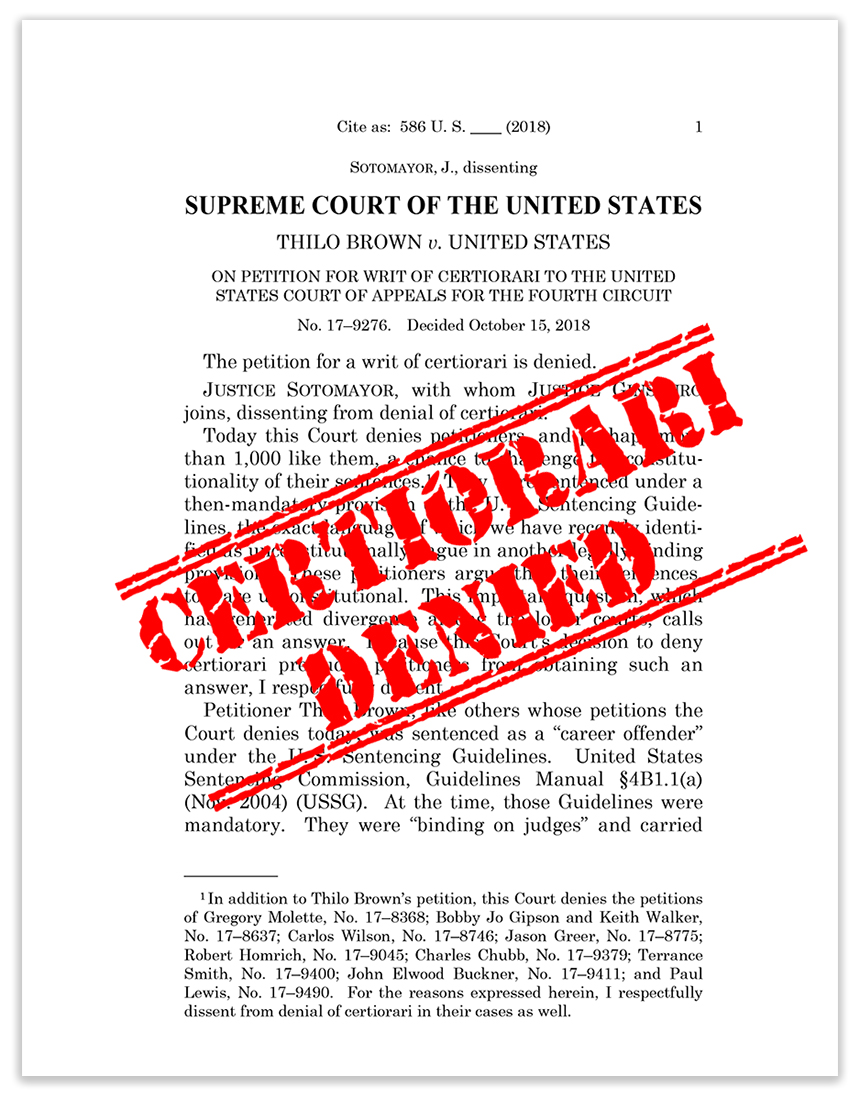

By a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court yesterday upheld the categorical approach to judging whether offenses were crimes of violence, ruling that 18 USC § 924(c)(3)(B) is unconstitutionally vague.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in the majority opinion that “[i]n our constitutional order, a vague law is no law at all.”

The vagueness doctrine rests on the twin constitutional pillars of due process and separation of powers. Having applied the doctrine in two cases involving statutes that “bear more than a passing resemblance to § 924(c)(3)(B)’s residual clause” – those being Johnson v. United States (Armed Career Criminal Act residual clause unconstitutional) and Sessions v. Dimaya (18 USC § 16(b) residual clause unconstitutional) – the Court completed its frolic through the residual clauses in the criminal code.

The vagueness doctrine rests on the twin constitutional pillars of due process and separation of powers. Having applied the doctrine in two cases involving statutes that “bear more than a passing resemblance to § 924(c)(3)(B)’s residual clause” – those being Johnson v. United States (Armed Career Criminal Act residual clause unconstitutional) and Sessions v. Dimaya (18 USC § 16(b) residual clause unconstitutional) – the Court completed its frolic through the residual clauses in the criminal code.

Courts use the “categorical approach” to determine whether an offense qualified as a violent felony or crime of violence. Judges had to disregard how the defendant actually committed the offense and instead imagine the degree of risk that would attend the idealized “‘ordinary case’ ” of the offense.

The lower courts have long held § 924(c)(3)(B) to require the same categorical approach. After the 11th Circuit’s decision in Ovalles, the government advanced the argument everywhere that for § 924(c)(3)(B), courts should abandon the traditional categorical approach and use instead a case-specific approach that would look at the defendant’s actual conduct in the predicate crime.

The Supreme Court rejected that, holding that while the case-specific approach would avoid the vagueness problems that doomed the statutes in Johnson and Dimaya and would not yield to the same practical and Sixth Amendment complications that a case-specific approach under the ACCA and § 16(b) would, “this approach finds no support in § 924(c)’s text, context, and history.”

The government campaign came to a head in Davis, a 5th Circuit case in which the appellate court said that conspiracy to commit a violent crime was not a crime of violence, because it depended on the § 924(c)(3)(B) residual clause. The Dept. of Justice felt confident enough to roll the dice on certiorari. Yesterday, the DOJ had its hat handed to it.

The government campaign came to a head in Davis, a 5th Circuit case in which the appellate court said that conspiracy to commit a violent crime was not a crime of violence, because it depended on the § 924(c)(3)(B) residual clause. The Dept. of Justice felt confident enough to roll the dice on certiorari. Yesterday, the DOJ had its hat handed to it.

Who does this benefit? Principally, it benefits anyone who received a § 924(c) enhanced sentence for an underlying conspiracy charge. Beyond that, it helps anyone else whose “crime of violence” depended on the discredited § 924(c)(3)(B) residual clause.

The Court did not rule that Davis is retroactive for 28 USC § 2255 post-conviction collateral attack purposes, because that question was not before it. SCOTUS never rules on retroactivity in the same opinion that holds a statute unconstitutional. There is little doubt that, if Johnson was retroactive because of Welch, Davis will be held to be retro as well.

United States v. Davis, Case No. 18-431 (Supreme Court, June 24, 2019)

ARE 59(e) MOTIONS ‘SECOND OR SUCCESSIVE’ 2255s?

A number of lower courts have ruled that an unsuccessful § 2255 movant who files a motion to alter the judgment under Fed.R.Civ.P. 59(e) may be filing a second-or-successive § 2255 motion requiring prior approval.

This leaves § 2255 movants with a Hobson’s choice. Filing a 59(e) stays the time for filing a notice of appeal. But if the court sits on the 59(e) past the notice of appeal deadline, and then dismisses it as second-or-successive, the § 2255 movant has missed the notice of appeal deadline with the Court of Appeals. If the movant files a notice of appeal to preserve his or her rights, that nullifies the 59(e).

This leaves § 2255 movants with a Hobson’s choice. Filing a 59(e) stays the time for filing a notice of appeal. But if the court sits on the 59(e) past the notice of appeal deadline, and then dismisses it as second-or-successive, the § 2255 movant has missed the notice of appeal deadline with the Court of Appeals. If the movant files a notice of appeal to preserve his or her rights, that nullifies the 59(e).

Right now, the only logical election is to ignore Rule 59(e) motions altogether.

Yesterday, the Court granted review in yet another “Davis” case, asking whether the 59(e) motion should be considered second or successive such that it requires the grant of permission under 28 USC § 2244. We’ll have an answer next year.

Banister v. Davis, Case No. 18-6943 (certiorari granted, June 24, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root