We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

NUTZPAH

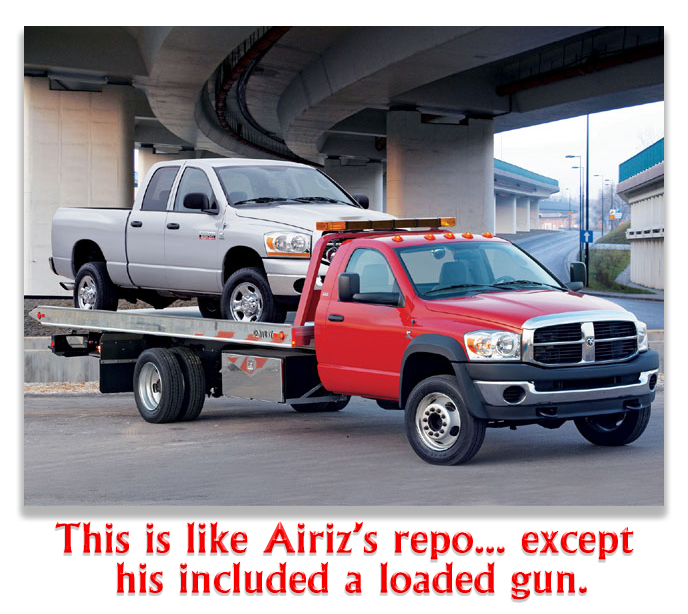

The facts of the case hardly seem like a federal crime. Repo man Garry Valentine showed up at Airiz Coleman’s house in Youngstown, Ohio, to repossess Airiz’s truck for nonpayment of the note. Airiz took exception, and – as the court drily puts it – “pointed a handgun approximately six or seven inches from Valentine’s face and threatened to kill him. Defendant’s wife intervened and Valentine was able to call the police.” The police came and arrested Airiz, seizing some cheap 5-shot revolver.

The facts of the case hardly seem like a federal crime. Repo man Garry Valentine showed up at Airiz Coleman’s house in Youngstown, Ohio, to repossess Airiz’s truck for nonpayment of the note. Airiz took exception, and – as the court drily puts it – “pointed a handgun approximately six or seven inches from Valentine’s face and threatened to kill him. Defendant’s wife intervened and Valentine was able to call the police.” The police came and arrested Airiz, seizing some cheap 5-shot revolver.

So far, it seems unremarkable, the kind of thing the local cops would handle. Airiz would be charged with some kind of assault, spend some time in jail, get bailed out, cop a plea and get maybe 6 months. Except, of course, it turns out Airiz had a prior felony, so the feds – who should have better things to do in Youngstown – picked up the case, charging Airiz with being a felon in possession of a firearm.

This is where the case gets interesting. While awaiting trial, Airiz apparently became acquainted with the Sovereign Citizen movement. We’ve described it before. The sovereign citizen movement is a loose grouping of litigants, commentators, tax protesters, financial-scheme promoters, and assorted whackos, who take the position that they are answerable only to their particular interpretation of the common law and are not subject to the United States Code or federal courts, although some of them have great affection for the Uniform Commercial Code (as they understand it to be, which it is not). Others prefer admiralty law. They do not recognize United States currency, although they freely spend it, and maintain that they are “free of any legal constraints.” They have special enmity for the federal income tax.

This is where the case gets interesting. While awaiting trial, Airiz apparently became acquainted with the Sovereign Citizen movement. We’ve described it before. The sovereign citizen movement is a loose grouping of litigants, commentators, tax protesters, financial-scheme promoters, and assorted whackos, who take the position that they are answerable only to their particular interpretation of the common law and are not subject to the United States Code or federal courts, although some of them have great affection for the Uniform Commercial Code (as they understand it to be, which it is not). Others prefer admiralty law. They do not recognize United States currency, although they freely spend it, and maintain that they are “free of any legal constraints.” They have special enmity for the federal income tax.

Airiz became an eager convert. At his arraignment, he acknowledged his but challenged the court’s jurisdiction over him, arguing that the government was “trying to charge him with” a “commercial crime” and that the United States could not be the victim of a commercial crime, whatever that meant. Airiz demanded of the magistrate judge to know if he was forcing Airiz “to contract,” and he referred to himself as a “flesh and blood living being.” He claimed that his detention on “U.S. soil” was unconstitutional.

When his public defender tried to quit because Airiz was “combative” and “confrontational,” Airiz told the court that he was present “on special appearance, as a third-party intervenor” and claimed that he was a “beneficiary and executor to the legal estate of the decedent.” He said he had surrendered his birth certificate “to the Court for set-off, settlement.” He contended that he was not a corporation, an estate, or a legal fiction, but rather, was “a living man… living private on the land.” He “authorized” the court “to settle and close the account, case, constructive trust” and again argued the court lacked “jurisdiction” and referenced his “copyright.” The district court quickly came to see the public defender’s point, and appointed other counsel.

Several days before trial, Defendant repeated his jurisdiction claim, explaining again that he is “a living man… not a ‘corporate fiction’… [who] never signed any ‘Contract’ with the Public Defender’s Office.” He also appointed “Respondent: James S. Gwin” (who was the District Judge hearing the case) “as Trustee to settle and close” the case. Airiz signed the notice as his own “Authorized Representative” and listed an address in “Warren, Ohio Republic,” with a zip code in brackets. Airiz loaded up the record with an Affidavit of Ownership, Declaration of Nationality, Certificate/s of Titles, and Birth Certificates, and declared himself to be a “Moorish American National.” Using a favored sovereign citizen artifice of declaring a copyright in his own name, Airiz demanded payment of “1,000,000,000.00 PER HOUR UPON OCCURANCE [sic]” when anyone used his name.” Finally, for good measure, Airiz attached a proposed “Order of Dismissal With Prejudice” pursuant to “Rule 12(b)(1)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure” alleging lack of subject-matter and in personam jurisdiction.

Several days before trial, Defendant repeated his jurisdiction claim, explaining again that he is “a living man… not a ‘corporate fiction’… [who] never signed any ‘Contract’ with the Public Defender’s Office.” He also appointed “Respondent: James S. Gwin” (who was the District Judge hearing the case) “as Trustee to settle and close” the case. Airiz signed the notice as his own “Authorized Representative” and listed an address in “Warren, Ohio Republic,” with a zip code in brackets. Airiz loaded up the record with an Affidavit of Ownership, Declaration of Nationality, Certificate/s of Titles, and Birth Certificates, and declared himself to be a “Moorish American National.” Using a favored sovereign citizen artifice of declaring a copyright in his own name, Airiz demanded payment of “1,000,000,000.00 PER HOUR UPON OCCURANCE [sic]” when anyone used his name.” Finally, for good measure, Airiz attached a proposed “Order of Dismissal With Prejudice” pursuant to “Rule 12(b)(1)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure” alleging lack of subject-matter and in personam jurisdiction.

Trial with his new counsel did not go well. Airiz claimed that he did not want to testify at trial, but his new attorney insisted he could not argue effectively unless Airiz testified as to his view of what happened. Airiz said he and his wife “didn’t want to argue for a corporation,” and that was why he “tried to be respectful” and said that he wasn’t the defendant, but a man. He was convicted.

At sentencing, Airiz was starting to get it. He painted himself as having overcome a tough childhood to become a good family man, and said he had written a play that a record company was about to produce. He said that he had a job lined up in Hollywood with Charlie Sheen. He said he had saved another inmate’s life while jailed awaiting trial. He told the court he “never meant to dishonor anyone in this courtroom” and that he “always wanted to provide for my family.”

The district court sentenced him to 36 months, one month beneath the bottom of the sentencing range.

On appeal, Airiz somehow ended up being represented by Washington, D.C., megafirm Sidley Austin. His appellate counsel did just about the only thing it could do. It complained that its client was obviously nuts, and that the district court should have had his head examined. Or, in legalese, it argued that Airiz’s “bizarre statements over the course of multiple hearings and trial, and his interaction with his counsel—as reported by those attorneys—triggered reasonable cause to believe” that he did not understand the nature and consequences of the criminal proceedings and lacked the ability to consult with counsel to prepare his defense.

On appeal, Airiz somehow ended up being represented by Washington, D.C., megafirm Sidley Austin. His appellate counsel did just about the only thing it could do. It complained that its client was obviously nuts, and that the district court should have had his head examined. Or, in legalese, it argued that Airiz’s “bizarre statements over the course of multiple hearings and trial, and his interaction with his counsel—as reported by those attorneys—triggered reasonable cause to believe” that he did not understand the nature and consequences of the criminal proceedings and lacked the ability to consult with counsel to prepare his defense.

Airiz offered a few examples: He said the “first tell-tale sign was his ‘stringing together legal jargon that made no sense’,” such as saying he was

“here on special appearance, third-party intervenor, okay, who was injured by this action, and beneficiary and executor to the legal estate of the decedent” He also believed that he could authorize the district court “to settle and close” the case and that he could “decline any more offers of imprisonment, fines, fees, or any other penalties.” Second, Defendant argues that he “utterly fail[ed] to grasp that the jury had convicted him of a federal criminal offense[.]” At the hearing to remove Mack as counsel, Defendant repeatedly insisted that his “debt” had been taken care of, and the court was therefore required to release him from custody. Third, Defendant claims that his “abnormal splintering of the self” should have raised a red flag. At the hearing on his first attorney’s motion to withdraw, Defendant characterized himself as the defendant’s “surety,” and at trial, as his “authorized representative.” In his objections to the presentence report, Defendant claimed that he was not a defendant, but “a natural living man” (and not a U.S. citizen). Fourth, he displayed “a grandiose belief in his own superior knowledge,” via his “belligerence with the prosecutor while being cross-examined at trial.” In particular, Defendant confusingly discussed his 2008 felony convictions, first claiming that he prevailed, then that he had taken a plea, and finally claiming that he had done so “unconsciously.” He also read a “revised” passage from the Bill of Rights—his version of that document. Fifth, although “fairly lucid” at sentencing, Defendant allegedly made “lofty claims that suggested he was not fully connected to reality.” This included his assertion that he was writing a play and had a “guaranteed job on anger management in L.A. with Charlie Sheen.”

In fact, Airiz argued, the district court itself twice commented that Defendant was not making any sense.

It was a pretty gutsy move: act nuts with a side of chutzpah. Call it “nutzpah.” Spout nonsense at trial, and then appeal on the grounds that the court should have known you were acting crazy. But earlier this week, the 6th Circuit refused to buy it. There was nothing that unusual about Airiz’s “meritless rhetoric,” which was “frequently espoused by tax protesters, sovereign citizens, and self-proclaimed Moorish-Americans.” The jurisdiction claims, the “Moorish-American” business, the name copyright, the “third-party intervenor” status: been there, the Court said. Done that. Have the Sovereign Citizen t-shirt.

It was a pretty gutsy move: act nuts with a side of chutzpah. Call it “nutzpah.” Spout nonsense at trial, and then appeal on the grounds that the court should have known you were acting crazy. But earlier this week, the 6th Circuit refused to buy it. There was nothing that unusual about Airiz’s “meritless rhetoric,” which was “frequently espoused by tax protesters, sovereign citizens, and self-proclaimed Moorish-Americans.” The jurisdiction claims, the “Moorish-American” business, the name copyright, the “third-party intervenor” status: been there, the Court said. Done that. Have the Sovereign Citizen t-shirt.

The 6th noted that two other circuits had rejected the claim that professing to be a sovereign citizen was “an expression of incompetency,” in the absence of mental illness or uncontrollable behavior. A competency hearing is not necessary where the only evidence of incompetence is “the unusual nature of the defendant’s beliefs.”

The appeals court held that Airiz showed that he understood the criminal nature of the proceedings, as reflected by the fact that he challenged the court’s jurisdiction. Airiz “demonstrated his ability to make legal arguments, albeit atypical ones. He drafted a detailed affidavit, provided state documents, and cited case law, statutes, and constitutions. His trial testimony was designed to counter incriminating facts.” He cooperated with the Probation Officer in preparation of the presentence report. But “perhaps most telling” was Airiz’s “articulate, passionate allocution” begging the court to return him to his family. The Court said that Airiz’s “swan song at sentencing reflects a carefully crafted attempt to present himself as a virtuous man, good father, and community leader, a character very different than the one presented at earlier stages of the proceedings.”

The appeals court held that Airiz showed that he understood the criminal nature of the proceedings, as reflected by the fact that he challenged the court’s jurisdiction. Airiz “demonstrated his ability to make legal arguments, albeit atypical ones. He drafted a detailed affidavit, provided state documents, and cited case law, statutes, and constitutions. His trial testimony was designed to counter incriminating facts.” He cooperated with the Probation Officer in preparation of the presentence report. But “perhaps most telling” was Airiz’s “articulate, passionate allocution” begging the court to return him to his family. The Court said that Airiz’s “swan song at sentencing reflects a carefully crafted attempt to present himself as a virtuous man, good father, and community leader, a character very different than the one presented at earlier stages of the proceedings.”

Yes, but how about Airiz’s claim of a Hollywood job offer? Was that not evidence of “grandiose and possibly delusional thinking.” The 6th Circuit thought not: “Given certain similarities between his behavior and Charlie Sheen’s behavior (both in real life and on television), it could also have been an attempt at rather ironic humor.”

Yes, but how about Airiz’s claim of a Hollywood job offer? Was that not evidence of “grandiose and possibly delusional thinking.” The 6th Circuit thought not: “Given certain similarities between his behavior and Charlie Sheen’s behavior (both in real life and on television), it could also have been an attempt at rather ironic humor.”

United States v. Coleman, Case No. 16-3972 (6th Cir., Sept. 13, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

NEWS FROM THE WHITE HOUSE

NEWS FROM THE WHITE HOUSE The New York Times reported last week that in the middle of an Oval Office “horsewhipping” of Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III by President Trump last May, over Sessions’ recusal of himself from the Trump Russia probe, the President got a phone call informing him that Robert Mueller had been appointed to be special counsel for the investigation. After the call, Trump “lobbed a volley of insults at Mr. Sessions, telling the attorney general it was his fault they were in the current situation. Mr. Trump told Mr. Sessions that choosing him to be attorney general was one of the worst decisions he had made, called him an “idiot,” and said that he should resign.”

The New York Times reported last week that in the middle of an Oval Office “horsewhipping” of Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III by President Trump last May, over Sessions’ recusal of himself from the Trump Russia probe, the President got a phone call informing him that Robert Mueller had been appointed to be special counsel for the investigation. After the call, Trump “lobbed a volley of insults at Mr. Sessions, telling the attorney general it was his fault they were in the current situation. Mr. Trump told Mr. Sessions that choosing him to be attorney general was one of the worst decisions he had made, called him an “idiot,” and said that he should resign.” Also from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, President Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner, hosted a White House roundtable last week to gather recommendations for improving mentoring and job training in federal prisons.

Also from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, President Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser, Jared Kushner, hosted a White House roundtable last week to gather recommendations for improving mentoring and job training in federal prisons.  Kushner’s interest in criminal justice policy is much different than that of Trump and Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, reportedly branded an “idiot”by his boss, who have called for more aggressive prosecutions of drug offenders and illegal immigrants.

Kushner’s interest in criminal justice policy is much different than that of Trump and Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, reportedly branded an “idiot”by his boss, who have called for more aggressive prosecutions of drug offenders and illegal immigrants.