We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

A PASSEL OF FAIR SENTENCING ACT RULINGS

Last week brought a pile of rulings on retroactive Fair Sentencing Act motions brought under Section 404 of the First Step Act.

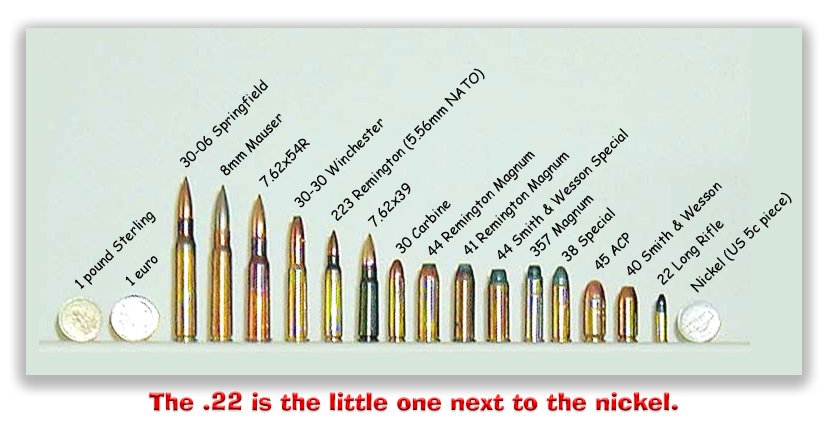

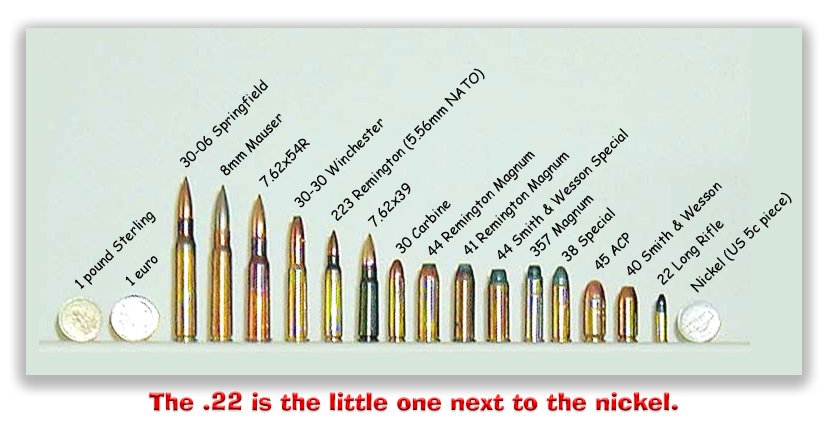

(Skip this if you know what I’m talking about). The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, of course, is the law that changed how defendants with crack (cocaine base) were punished. Back in the paranoid days of the late 1980s, crack was considered to be the scourge of the inner cities, terribly addictive compared to powder cocaine, dirt cheap and sold by people who were crazily violent and armed with an arsenal that Kim Jong Eun would envy. Congress responded thoughtfully by passing the Anti Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which mandated punishment for crack dealers as though they had sold 100 times as much powder cocaine. Really. 100:1. Selling crack that weighed no more that a .22 cal. bullet (the pointy lead thing, not the whole cartridge) was akin to selling a half-pound of cocaine powder.

Congress was right about one thing. Crack was a plague of the inner cities, because users could by enough to induce a high for a lot less than cocaine powder. What this meant was that the people who sold it were overwhelmingly black. The net effect of the ADA was to hang horrific sentences on blacks, while their white suburban counterparts who peddled powder faced much lighter sentences for essentially selling the same amount of drug.

Think I’m kidding? Proper cooking of powder cocaine ( to that I suggest you try this at home) should yield about 89%. That is, one kilo of coke powder should give you about 9/10th kilos of crack. Under the ADA, sell the powder and get five years (63 months minimum sentencing range under the then-current Guidelines). Cook the powder and sell the crack, and your minimum sentencing range would be 235 months.

Subsequent studies debunked the myth that crack was ore addictive than powder, and that crack distribution occasioned more violence than powder sales. But the law persisted until 2010, when Congress passed the FSA. The FSA cut the penalties from a ratio of 100:1 down to 18:1. The 1:1 people tried their hardest, but some compromise was needed to pass the Senate. Likewise, the FSA proponents had to give up their hope it would be retroactive to people serving long sentences already. To appease the troglodytes in the Senate, retroactivity was jettisoned, too.

In the First Step Act, Congress finally made the FSA retroactive. Under Section 404 of First Step, a person serving a crack sentence imposed before the FSA could apply for a sentence reduction, which the judge could grant or refuse to grant as a matter of discretion. (End background – you may resume reading).

Tony Denson, a federal prisoner, appealed the district court’s order reducing his crack sentence under Sec. 404. Without a hearing, the district court granted Tony’s motion, cutting his 262-month sentence to 188 months. The reduction was less than what Tony anticipated, so he appealed, arguing the district court erred by not holding a hearing.

Tony Denson, a federal prisoner, appealed the district court’s order reducing his crack sentence under Sec. 404. Without a hearing, the district court granted Tony’s motion, cutting his 262-month sentence to 188 months. The reduction was less than what Tony anticipated, so he appealed, arguing the district court erred by not holding a hearing.

The 11th Circuit shot him down, holding that under Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 43, Tony’s presence was not required in a § 3582(c) proceeding, and that’s all a Sec. 404 resentencing is. The Circuit joined the 5th and 8th Circuits in holding that a defendant has no right to a hearing on a Fair Sentencing Act resentencing.

In the 8th Circuit, a district court denied Jonair Moore’s Sec. 404 motion, holding that he had dealt in too much coke and crack (11 kilos of powder, 1.2 kilos of rock) for the court to want to cut his time. Also, the judge said, Jon had obstructed and used a gun in the drug crimes, so his 230-month sentence seemed right.

Jon appealed, arguing that on a Sec. 404 resentencing, the judge had to apply the 18 USC § 3553(a) sentencing factors to any decision. The 8th disagreed.

“Section 404 is permissive,” the Circuit ruled. “A district court ‘may’ impose a reduced sentence. Nothing in this section shall be construed to require a court to reduce any sentence under the section.” Furthermore, the 8th said, Sec. 404 nowhere mention the § 3553 factors: “When Congress intends to mandate consideration of the section 3553 factors, it says so,” the panel wrote, citing 18 USC §3582(c)(2) (stating a court may impose a reduced sentence after considering the factors set forth in section 3553(a)…) In the First Step Act, Congress does not mandate that district courts analyze the section 3553 factors for a permissive reduction in sentence.”

Meanwhile, the 4th Circuit issued an explanation for its earlier order than Al Woodson be resentenced. Al was sentenced under 21 USC 841(b)(1)(C) for distribution of 4 grams of crack. Subsection 841(b)(1)(C) had no mandatory minimum sentence. Ten years later, Woodson filed a motion for a reduced sentence First Step Act Sec. 404, believing he was eligible for relief because he was convicted for a crack cocaine offense prior to 2010. The district court denied his motion on the ground that Sec. 404 does not apply to crack offenders sentenced under 841(b)(1)(C).

The 4th disagreed. It held that the FSA modified 841(b)(1)(C) by altering the crack cocaine quantities to which its penalty applies. Before the FSA, 841(b)(1)(C)’s penalty applied only to offenses involving less than 5 grams of crack cocaine. Because of the FSA, the penalty in Subsection 841(b)(1)(C) now covers offenses involving between 5 and 28 grams of crack cocaine as well.

The scope of 841(b)(1)(C)’s penalty for crack cocaine is defined by reference to 841(b)(1)(A) and (B): 841(b)(1)(C) imposes a penalty of not more than 20 years for crack trafficking offenses “except as provided in subparagraphs (A) [and] (B).” Thus, by increasing the drug weights to which the penalties in 841(b)(1)(A)(iii) and (B)(iii) applied, the Circuit held, Congress also increased the crack cocaine weights to which 841(b)(1)(C) applied, too.

United States v. Denson, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 19636 (11th Cir. June 24, 2020)

United States v. Moore, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 19616 (8th Cir. June 24, 2020)

United States v. Woodson, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 19700 (4th Cir. June 24, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root

In Terry v. United States, the justices agreed to hear a technical sentencing issue with significant implications for thousands of inmates: whether defendants who were sentenced for low-level crack-cocaine offenses under 21 USC § 841(b)(1)(C) before Congress enacted the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 are eligible for resentencing under the First Step Act of 2018.

In Terry v. United States, the justices agreed to hear a technical sentencing issue with significant implications for thousands of inmates: whether defendants who were sentenced for low-level crack-cocaine offenses under 21 USC § 841(b)(1)(C) before Congress enacted the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 are eligible for resentencing under the First Step Act of 2018. Finally, one that everyone expected: the Court granted the government certiorari in United States v. Gary, to determine whether the 4th Circuit is right that a Rehaif v. United States error is structural, meaning that a defendant does not have to prove that he or she was prejudiced by the court’s failure to instruct on all elements of the 18 USC § 922(g) felon-in-possession offense.

Finally, one that everyone expected: the Court granted the government certiorari in United States v. Gary, to determine whether the 4th Circuit is right that a Rehaif v. United States error is structural, meaning that a defendant does not have to prove that he or she was prejudiced by the court’s failure to instruct on all elements of the 18 USC § 922(g) felon-in-possession offense.

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a

The 7th Circuit last week held that the same rule benefitted Rashod Bethany. Rashod was sentenced for a crack conspiracy in 2013, but later won a

A few years ago, the 9th Circuit had ruled that the some of Ezralee’s Washington state convictions used back in 2006 to make her a career offender do not count toward career offender. As a result, Ezralee said, she should be resentenced without the career status, which should drop her from 262-327 to a 51-month range.

A few years ago, the 9th Circuit had ruled that the some of Ezralee’s Washington state convictions used back in 2006 to make her a career offender do not count toward career offender. As a result, Ezralee said, she should be resentenced without the career status, which should drop her from 262-327 to a 51-month range.