We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

6th CIRCUIT SAYS GUIDELINES CAREER OFFENDERS WANTING HAVIS OR DAVIS ADJUSTMENTS ARE OUT OF LUCK

Dwight Bullard pleaded guilty to distributing heroin and being a felon in possession of a firearm. At sentencing, the district court determined that he qualified as a career offender under the Sentencing Guidelines, a provision that sets sentencing ranges stratospherically high for people convicted of two prior drug crimes or crimes of violence.

Dwight Bullard pleaded guilty to distributing heroin and being a felon in possession of a firearm. At sentencing, the district court determined that he qualified as a career offender under the Sentencing Guidelines, a provision that sets sentencing ranges stratospherically high for people convicted of two prior drug crimes or crimes of violence.

One of Dwight’s prior drug offenses was for attempted to sell drugs. After the 6th Circuit’s decision in United States v. Havis, which held that attempted drug crimes did not qualify a predicate offense for Guidelines career offender status, Ballard challenged his own Guidelines career offender status in a post-conviction motion under 28 USC § 2255.

The difference between being a career offender and not being a career offender is huge, sometimes the difference between under five years and nearly 20 years in prison. The sentencing ranges are advisory, of course – courts are not obligated to follow them, but do over half of the time – but nevertheless the sentencing ranges are very influential.

The district court denied his 2255 motion, so Dwight appealed.

On appeal, the government admitted that Dwight was right, because Havis held the Guidelines definition of a controlled substance offense does not include attempt crimes. The 6th Circuit agreed that if Dwight received his sentence today, he would not be a Guidelines career offender.

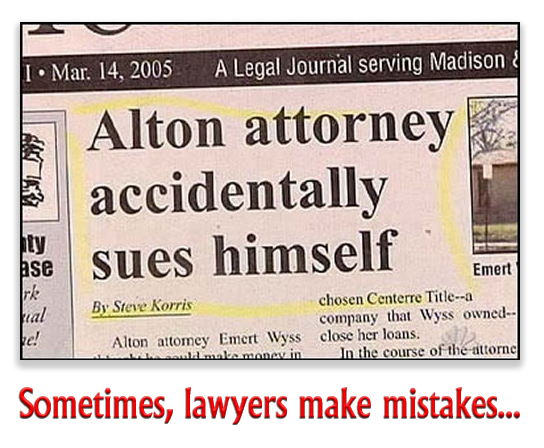

But a non-constitutional challenge to an advisory guidelines range may not be raised in a post-conviction motion such as a 2255. Ballard tried to get around that problem by claiming that his trial and appeals attorneys were ineffective, because they did not raise the argument that ultimately won in Havis. Ineffective of counsel is a Sixth Amendment claim, and thus a constitutional issue.

But a non-constitutional challenge to an advisory guidelines range may not be raised in a post-conviction motion such as a 2255. Ballard tried to get around that problem by claiming that his trial and appeals attorneys were ineffective, because they did not raise the argument that ultimately won in Havis. Ineffective of counsel is a Sixth Amendment claim, and thus a constitutional issue.

Nevertheless, the 6th Circuit upheld dismissal of Dwight’s 2255. While his claim was cognizable under 2255, the Court said, Dwight could not show that his attorneys were ineffective for not raising the issue, and even if they had been, he had suffered no prejudice.

Before Havis, there was no case precedent in the Circuit that would have held Dwight’s Arizona prior not to be a controlled substance offense. That being the case, the Circuit held, it was entirely reasonable for Dwight’s trial counsel not to object that the prior was used to make Dwight a career offender. As it is, his trial attorney argued at sentencing that Dwight was not “an authentic career offender,” and thus got him sentenced 152 months under his minimum Guidelines.

Before Havis, there was no case precedent in the Circuit that would have held Dwight’s Arizona prior not to be a controlled substance offense. That being the case, the Circuit held, it was entirely reasonable for Dwight’s trial counsel not to object that the prior was used to make Dwight a career offender. As it is, his trial attorney argued at sentencing that Dwight was not “an authentic career offender,” and thus got him sentenced 152 months under his minimum Guidelines.

Even if Dwight’s lawyer should have raised the same argument that later won in Havis, the 6th Circuit held, the district court outcome would not have been different. This is because under the case law at the time, the district court would have counted the Arizona conviction toward career offender status even if Dwight’s lawyer had objected.

In so many words, the 6th Circuit says people who received career offender sentences because of what courts now recognize as a mistake, people who would never qualify for such a status today because of Havis or Davis, are simply out of luck.

Bullard v. United States, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 26643 (6th Cir. Sept. 4, 2019)

– Thomas L. Root