We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THREE UNRELATED STORIES MAY PORTEND CHANGE IN COMPASSIONATE RELEASE

Sometimes, interesting stories come in triplicate.

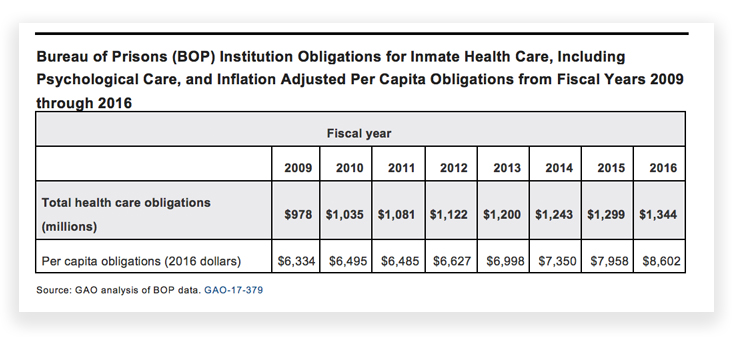

Story 1: Late last week, the Government Accountability Office reported that the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ cost of providing healthcare to inmates had jumped 30% in the last four years. The BOP now spends over $8,600 per year to meet each inmate’s health needs.

Story 1: Late last week, the Government Accountability Office reported that the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ cost of providing healthcare to inmates had jumped 30% in the last four years. The BOP now spends over $8,600 per year to meet each inmate’s health needs.

The GAO report found that while the BOP knows how much it is spending on healthcare, it lacks utilization data, “which is data that shows how much it is spending on individual inmate’s health care or how much it is expending on a particular health care service.” A 2015 Dept. of Justice Inspector General’s study contained the unsurprising report that aging inmates cost more to incarcerate due to higher healthcare costs.

At the same time, number of 55-year old and older inmates has increased from 8.4% of the inmate population in 2009 to 12.0% in FY 2016.

At the same time, number of 55-year old and older inmates has increased from 8.4% of the inmate population in 2009 to 12.0% in FY 2016.

Story 2: Under 18 USC 3582(c)(1), the BOP director is empowered to recommend the compassionate release of an aged, infirm or sick inmate to his or her sentencing judge. The district court then makes the call whether to release the prisoner or not. It is an open secret that while the BOP constantly wrings its bureaucratic hands over its soaring costs of inmate care, an inmate has perhaps a better chance of being struck by lightning than he or she does being recommended or compassionate release. On average, about 575 applications for compassionate release are filed annually: the number actually granted averages about 24.

Story 2: Under 18 USC 3582(c)(1), the BOP director is empowered to recommend the compassionate release of an aged, infirm or sick inmate to his or her sentencing judge. The district court then makes the call whether to release the prisoner or not. It is an open secret that while the BOP constantly wrings its bureaucratic hands over its soaring costs of inmate care, an inmate has perhaps a better chance of being struck by lightning than he or she does being recommended or compassionate release. On average, about 575 applications for compassionate release are filed annually: the number actually granted averages about 24.

In 2013, the DOJ Inspector General encouraged the BOP to step up its game. Two years later, the IG’s aging inmates study found “aging inmates engage in fewer misconduct incidents while incarcerated and have a lower rate of re-arrest once released.” In 2016, the U.S. Sentencing Commission went so far as to expand eligibility for the program in hopes the BOP would use it more.

The BOP has remained remarkably immune to DOJ’s exhortations and the Sentencing Commission’s gentle prodding. Late last week, Congress stepped into the breach.

In a report accompanying the 2018 appropriations bill, Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Alabama) – chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies – ordered the BOP to turn over a gold mine of data on the compassionate release program. Sen. Shelby wants to see (1) the steps BOP has taken to implement the IG’s and Sentencing Commission’s suggestions; (2) a detailed explanation as to which recommendations the BOP has not adopted (which we think would be all of them) and why they were rejected; (3) the number of prisoners seeking compassionate release in each of the last five years, how many were granted and how many denied (“categorized by the criteria relied on as grounds” for each decision, as the Report puts it); (4) the amount of time between each request being filed and being acted on; and (4) how many inmates died while waiting for a BOP compassionate release decision .

In a report accompanying the 2018 appropriations bill, Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Alabama) – chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies – ordered the BOP to turn over a gold mine of data on the compassionate release program. Sen. Shelby wants to see (1) the steps BOP has taken to implement the IG’s and Sentencing Commission’s suggestions; (2) a detailed explanation as to which recommendations the BOP has not adopted (which we think would be all of them) and why they were rejected; (3) the number of prisoners seeking compassionate release in each of the last five years, how many were granted and how many denied (“categorized by the criteria relied on as grounds” for each decision, as the Report puts it); (4) the amount of time between each request being filed and being acted on; and (4) how many inmates died while waiting for a BOP compassionate release decision .

Sen. Shelby is giving the BOP 60 days to deliver the data.

As of last June, about 35,000 federal prisoners are over the age of 51. More than 10,000 of those inmates are over 60.

Story 3: There’s a new sheriff in town. Yesterday, Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III announced that Army Major General Mark Inch will serve as the new BOP director, replacing acting director Thomas Kane.

Sessions said, “As a military policeman for nearly a quarter of a century and as the head of Army Corrections for the last two years, General Inch is uniquely qualified to lead our federal prison system.”

Sessions said, “As a military policeman for nearly a quarter of a century and as the head of Army Corrections for the last two years, General Inch is uniquely qualified to lead our federal prison system.”

Inch, who as Provost Marshal General of the Army and Commanding General, United States Army Criminal Investigation Command and Army Corrections Command, was the Army’s top cop, has been a soldier for 35 years. He has professional certification with the American Correctional Association (ACA) and was the first Army officer to earn the Certified Corrections Executive designation with Honor.

Wrap-up: We’re just speculating here, but Inch – who led the Army Corrections Command after the international embarrassment at US-run Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq – is an outsider to the BOP and a man who is used to the chain of command. He may be more likely to follow the directives of Congress and the DOJ, and be open to the guidance of the Sentencing Commission – while at the same time being resistant to the “we’ve-always-done-it-that-way” mentality of the agency he has been tasked to lead.

In short, this could be a pivotal moment for the BOP Director’s exercise of the compassionate release power under 18 USC 3582(c)(1).

Government Accountability Office, Better Planning and Evaluation Needed to Understand and Control Rising Inmate Health Care Costs (July 27, 2017)

Senate Committee on Appropriations, Draft Report on Commerce and Justice, Science and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2018 (July 25, 2017)

The Hill, Sessions adds Army general to oversee federal prisons (Aug. 1, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root