We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WHAT’S IN A WORD?

Bob Cross is doing life by the installment plan. He caught a marijuana case (or marihuana, as the government would put it) 2006, and sentenced to 60 months in prison, followed by four years of supervised release.

In August 2010, Bob got out and started his supervised release term, which – for those of you who have had the enjoyment of crossing swords with the federal criminal justice system – is nothing but glorified parole, and a seemingly endless bad dream to boot. Essentially, during supervised release, an offender has to file a monthly report on a form that is as vague and all-encompassing as the federal criminal code itself, and must adhere to equally spongy conditions. Violating the conditions is as easy as walking out your front door in the morning, leaving an offender’s continued freedom pretty much at the mercy of his or her probation officer (and, of course, the court for which the probation officer works).

In August 2010, Bob got out and started his supervised release term, which – for those of you who have had the enjoyment of crossing swords with the federal criminal justice system – is nothing but glorified parole, and a seemingly endless bad dream to boot. Essentially, during supervised release, an offender has to file a monthly report on a form that is as vague and all-encompassing as the federal criminal code itself, and must adhere to equally spongy conditions. Violating the conditions is as easy as walking out your front door in the morning, leaving an offender’s continued freedom pretty much at the mercy of his or her probation officer (and, of course, the court for which the probation officer works).

You’ve heard the old business aphorism, “The customer is always right?” See how that applies when you’re arguing to a district court that the opinion of a probation officer on whom the court relies for so much – and who is a judicial agency employee to boot – should be overruled. You may as well ask Donald Trump to overrule Melania or Ivanka.

Sometimes, however, the violation is fairly obvious. It was for Bob. During his supervised release term, Bob caught state drug possession and theft cases, both of which of course violated his supervised release conditions.

Sometimes, however, the violation is fairly obvious. It was for Bob. During his supervised release term, Bob caught state drug possession and theft cases, both of which of course violated his supervised release conditions.

The district court learned about the drug possession beef first, and revoked his supervised release in April 2013, ordering him to do 8 more months in prison and an additional two years of supervised release. In December 2013, Bob finished the 8 months in the cooler, and resumed his supervised release.

Fifteen months later, the district court finally tumbled to Bob’s 2012 theft conviction, and revoked his supervised release again. Apparently due to the age of the conviction and the fact it could have punished him before, the court sentenced him to a single day in jail and another five years of supervised release.

Bob appealed, arguing that the court had revoked his previous supervised release term when it gave him 8 months in prison, and that because it had revoked it, the court had no jurisdiction to revoke the new term for something – the theft – that had happened in the old term. On Wednesday, the 6th Circuit gave Bob a grammar lesson.

The Circuit explained that, “revocation and termination of supervised release are distinct concepts. Termination discharges the defendant and thereby ends the district court’s supervision of him. Thus, if the district court later discovered that the defendant had earlier violated some condition of his supervised release, the court would lack authority to send him back to prison for that violation qua violation. Revocation, in contrast, means that the defendant must “serve in prison all or part of the term of supervised release. Thus, revocation does not terminate the defendant’s supervised release; quite the contrary, it requires him to serve “all or part” of it in prison… Revocation therefore revokes only the release part of supervised release; the district court’s supervisory authority continues until the defendant’s supervised release terminates or expires.”

The Circuit explained that, “revocation and termination of supervised release are distinct concepts. Termination discharges the defendant and thereby ends the district court’s supervision of him. Thus, if the district court later discovered that the defendant had earlier violated some condition of his supervised release, the court would lack authority to send him back to prison for that violation qua violation. Revocation, in contrast, means that the defendant must “serve in prison all or part of the term of supervised release. Thus, revocation does not terminate the defendant’s supervised release; quite the contrary, it requires him to serve “all or part” of it in prison… Revocation therefore revokes only the release part of supervised release; the district court’s supervisory authority continues until the defendant’s supervised release terminates or expires.”

The Court held that because the district court’s authority continues throughout an offender’s supervised release term, so too does the court’s ability to police violations of the release’s conditions. Here, Bob’s supervised release term – and the district court’s right to supervise it – had “neither terminated nor expired by June 2015.” Therefore, the district court could revoke Bob’s supervised release a second time based upon its discovery that he had committed a second violation, no matter where in the supervised release term it happened.

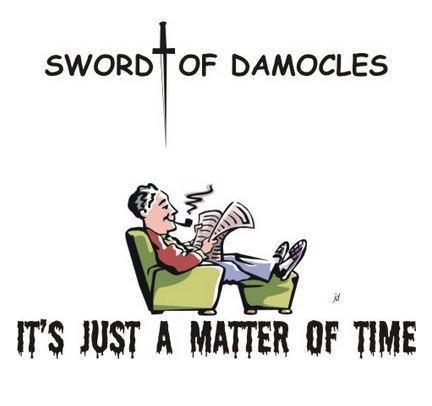

So Bob gets to live under the Sword of Damocles until summer 2020 (unless of course the district court finds another reason to prolong it even more). By then, Bob will be 15 years into a 5-year pot sentence.

So Bob gets to live under the Sword of Damocles until summer 2020 (unless of course the district court finds another reason to prolong it even more). By then, Bob will be 15 years into a 5-year pot sentence.

United States v. Cross, Case No. 15-5641 (6th Cir. Jan. 18, 2017).

– Thomas L. Root