We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

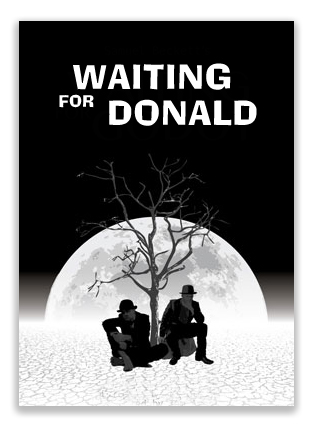

SENTENCE REFORM – WAITING FOR THE DONALD

We’ve been hearing since last year that leadership in the House and Senate intend to resurrect the Sentence Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 in some form this year. But – like the weather – everyone seems to talk about it, but no one is doing anything about it.

Thus far this legislative year, as we’ve noted, there has been a dearth of criminal justice reform legislation introduced in Congress. A report released yesterday by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University may hint at why.

On the subject of sentence reform, the Report notes that in January 2017, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), chair of the Senate Justice Committee, and House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) committed to reintroduce some version of the failed SRCA. However, the Report says, both Ryan and Grassley “are rumored to be waiting for the administration to announce its position before moving forward.”

On the subject of sentence reform, the Report notes that in January 2017, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), chair of the Senate Justice Committee, and House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wisconsin) committed to reintroduce some version of the failed SRCA. However, the Report says, both Ryan and Grassley “are rumored to be waiting for the administration to announce its position before moving forward.”

Rumors flew in March, when President Trump’s son-in-law and advisor Jared Kushner met with Grassley and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Illinois) – the top-ranking Democrat on the Committee, to discuss sentencing and reentry legislation. Kushner, whose father did federal time for white-collar offenses, has more reason than most to favor federal sentencing reform, and reports say that he does.

The Brennan Report says, “Trump’s personal positions on such bills are unknown. It remains to be seen whether any advice from Kushner and backing by conservative reform advocates will influence the President. Some conservatives support expanding reentry services, and modest sentencing reductions for low-level offenders. The Trump Administration could take a similar stance, backing modest prison reform in Congress while continuing to pursue aggressive new prosecution strategies.”

Elsewhere in the Report, the Brennan Center predicts that “recommendations for more punitive immigration, drug, and policing actions” will flow from the Administration over the next few months. It notes that a crime task force established by Attorney General Jeffrey Sessions is scheduled to deliver its first report by July 27. The Center foresees the task force calling for “a rescission of Obama-era memos on prosecutorial discretion, which helped decrease the federal prison population, and diverted low-level drug offenders away from incarceration.”

Brennan Center for Criminal Justice, Criminal Justice in President Trump’s First 100 Days (April 20, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

COMPASSIONATE KISSES

We watched with some glee a year ago when the U.S. Sentencing Commission horse-shedded the BOP over that agency’s chary use of compassionate release. It was fun while it lasted, but it didn’t last very long.

“Compassionate release,” a provision enshrined in 18 USC § 3582(c)(1), was enacted by Congress in the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984. Besides replacing the prior sentencing regime with the Guidelines, the Act strictly limited the ability of federal courts to revisit sentences once they became final (that is, the time for appellate review expired). Parole was eliminated, with sentences to be served fully (with an allowance of about 14% for good conduct in prison).

“Compassionate release,” a provision enshrined in 18 USC § 3582(c)(1), was enacted by Congress in the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984. Besides replacing the prior sentencing regime with the Guidelines, the Act strictly limited the ability of federal courts to revisit sentences once they became final (that is, the time for appellate review expired). Parole was eliminated, with sentences to be served fully (with an allowance of about 14% for good conduct in prison).

One safety valve crafted into the Act by Congress was to give courts the ability to modify or terminate sentences if prisoners were able to show “extraordinary and compelling” reasons justifying early release. Congress tasked the Sentencing Commission with the job of identifying the criteria to be used in determining whether a reason was “extraordinary and compelling.” The statute delegated BOP with the task of identifying prisoners who met these criteria. The idea was that the BOP would identify who qualified, and then petition the district court for grant of compassionate release. The district judge would make the final determination.

The entire process was considered by Congress to be an act of grace. Inmates have no right to petition the court directly under 18 USC 3582(c)(1). They may not seek judicial review of a BOP refusal to recommend release. They may not appeal a district court’s denial of compassionate release. This means the power to free a prisoner is placed in the hands of the jailer whose job it is to keep him locked up, who incidentally is represented by the prosecutor – the US Attorney – whose job it is to lock up federal criminal offenders.

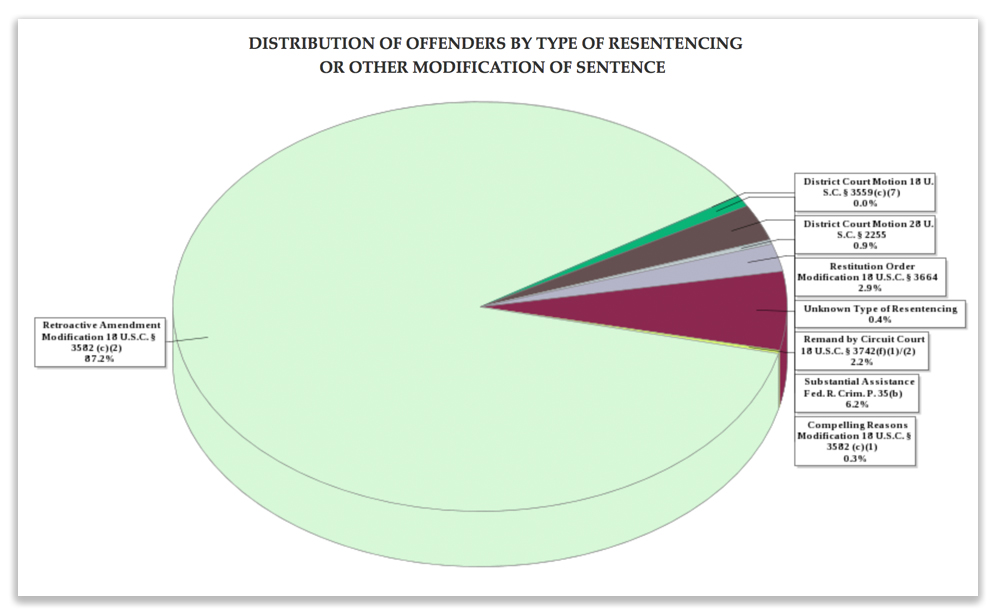

So how does the system work? We’ll let the numbers speak. In 2015, out of about 205,000 federal inmates, the BOP found extraordinary and compelling circumstances justifying compassionate release only 62 times. That works out to 0.03% (or about 3 prisoners out of every 10,000). Those odds stink. It’s hard to believe that so few prisoners qualify for compassionate release.

The BOP’s stinginess has drawn fire from the Sentencing Commission. At the April 2016 hearing we noted above, commissioners complained that the BOP had adopted its own definition of “extraordinary and compelling.” The criteria the Commission adopted directed the BOP to confine itself to determining if a prisoner meets the criteria the Sentencing Commission adopted, and – if so – bringing a motion for reduction in sentence to the district court.

The BOP’s stinginess has drawn fire from the Sentencing Commission. At the April 2016 hearing we noted above, commissioners complained that the BOP had adopted its own definition of “extraordinary and compelling.” The criteria the Commission adopted directed the BOP to confine itself to determining if a prisoner meets the criteria the Sentencing Commission adopted, and – if so – bringing a motion for reduction in sentence to the district court.

BOP’s management of compassionate release is no different than a district judge deciding that she would adopt her own definition of “career offender,” no matter what the Sentencing Commission might say in Chapter 4B of the Guidelines.

In an article published this week by Learn Liberty, Mary Price – general counsel to Families Against Mandatory Minimums – cited cases where even the most slam-dunk compassionate release cases took over a year for the BOP to process. She noted that the BOP was hurting itself as well as the affected inmates: compassionate release of elderly and infirm inmates makes economic as well as social sense, and saves the BOP from caring for the most expensive and least dangerous of its inmates.

In an article published this week by Learn Liberty, Mary Price – general counsel to Families Against Mandatory Minimums – cited cases where even the most slam-dunk compassionate release cases took over a year for the BOP to process. She noted that the BOP was hurting itself as well as the affected inmates: compassionate release of elderly and infirm inmates makes economic as well as social sense, and saves the BOP from caring for the most expensive and least dangerous of its inmates.

Ms. Price wrote that

if the BOP is unable or unwilling to treat the compassionate release program as Congress intended, Congress should take steps to ensure that prisoners denied or neglected by the BOP nonetheless get their day in court. Congress can do so by giving prisoners the right to appeal a BOP denial to court or to seek a decision from the BOP in cases… in which delays stretch out over months or even years. Such a right to an appeal will restore to the courts the authority that the BOP has usurped: to determine whether a prisoner meets compassionate release criteria and if so, whether he deserves to be released.

Institute for Humane Studies, George Mason University, Mary Price, How the Bureau of Prisons locked down “compassionate release” (Apr. 18, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

Glen filed a petition under

Glen filed a petition under