We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SUPREME COURT REJECTS EFFORT TO NARROW ACCA-PREDICATE DRUG CRIMES

The Supreme Court last week refused to extend the Taylor/Mathis “categorical” approach – an approach that has substantially narrowed the definition of a crime of violence – to “serious drug offense” prior convictions that can qualify a defendant for the Armed Career Criminal Act 15-year mandatory minimum.

A unanimous court held in Shular v. United States that the only thing that matters in analyzing whether a prior conviction is a “serious drug offense” is that the state offense involve the conduct specified in the ACCA, not that the state offense match some particular generic drug offense.

A primer: The ACCA is a penalty statute that applies to 18 USC § 922(g)(1), the so-called felon-in-possession statute. Section 922(g)(1) prohibits people with a prior conviction for a felony from possessing guns or ammo. The penalty for violating 922(g)(1) is set out in 18 USC 924(a), a sentence of zero to ten years in prison.

However, there’s a kicker. If the defendant has three prior convictions for crimes of violence, serious drug felonies (or a combination of the two), he or she is considered an “armed career criminal,” and the penalty skyrockets to a minimum of 15 years and a maximum of life. This enhanced penalty is set out in a different subsection, 18 USC § 924(e)(2), and is known as the Armed Career Criminal Act.

However, there’s a kicker. If the defendant has three prior convictions for crimes of violence, serious drug felonies (or a combination of the two), he or she is considered an “armed career criminal,” and the penalty skyrockets to a minimum of 15 years and a maximum of life. This enhanced penalty is set out in a different subsection, 18 USC § 924(e)(2), and is known as the Armed Career Criminal Act.

The ACCA includes definitions of what constitutes a crime of violence and what qualifies as a “serious drug felony.” The “crime of violence” definition has been the subject of a number of Supreme Court decisions in the last decade or so, including findings that one subsection – which provided that a crime was violent if it carried a substantial likelihood of physical harm – was unconstitutionally vague (Johnson v. United States, 2015). Judging whether and the requirement that when judging whether a state conviction was a crime of violence, the district court had to apply the “categorical approach.” Under that approach, one would not look at what the defendant was convicted of having done, but instead whether the offense could be committed (and reasonably would be prosecuted) without any violent physical conduct.

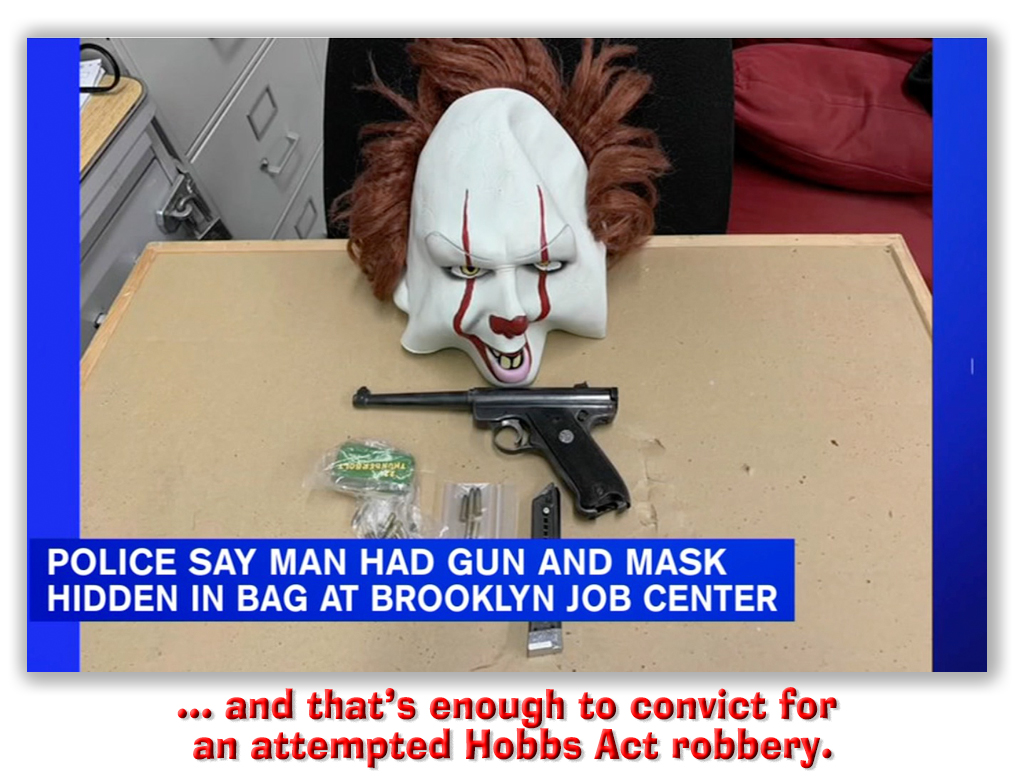

A good example of this is found in our review last month of Hobbs Act robbery. Everyone agrees that a robbery is violent – after all, use of force or threat of force is an element. But is an attempted Hobbs Act robbery violent? One can be convicted of attempted Hobbs Act robbery by walking up to the bank’s front door carrying a mask and a gun. That act requires no violence at all.

But for all of the ink that’s been spilled on ACCA crimes of violence, the “serious drug offense” definition has been unscathed. That definition provides that a prior drug conviction counts toward the ACCA’s three-conviction predicate only if it involves “manufacturing, distributing, or possessing with intent to manufacture or distribute, a controlled substance.” Seems simple. But it’s not.

But for all of the ink that’s been spilled on ACCA crimes of violence, the “serious drug offense” definition has been unscathed. That definition provides that a prior drug conviction counts toward the ACCA’s three-conviction predicate only if it involves “manufacturing, distributing, or possessing with intent to manufacture or distribute, a controlled substance.” Seems simple. But it’s not.

Defendant Eddie Shular argued that the terms in the statute are shorthand for the elements of the prior offense. He maintained that a district court had to first identify the elements of the “generic” drug offense, that is, the offense that Congress must have had in mind when it wrote the statute. The district court then had to ask whether the elements of the defendant’s prior state offense matched those of the generic crime.

This was important to Eddie, because he said his prior Florida drug convictions did not include a mens rea element, that is, they lacked the requirement that he had to know the substance he possessed was illegal.

Assume Eddie was right that the Florida statute lacked a mens rea requirement. Such a statute, that made it a felony to possess illegal drugs with an intention to distribute, would permit conviction of a little old lady who went to pick up her neighbor’s laxative at the drug store as a favor, but was accidentally given Oxycontin instead. After she gave the drug store bag to her neighbor, she would have possessed a controlled substance, and she would have distributed it. Eddie argued that a defective statute like that had to be measured against a generally-accepted generic PWITD statute, one that required the defendant know that he or she possessed an illegal substance.

Assume Eddie was right that the Florida statute lacked a mens rea requirement. Such a statute, that made it a felony to possess illegal drugs with an intention to distribute, would permit conviction of a little old lady who went to pick up her neighbor’s laxative at the drug store as a favor, but was accidentally given Oxycontin instead. After she gave the drug store bag to her neighbor, she would have possessed a controlled substance, and she would have distributed it. Eddie argued that a defective statute like that had to be measured against a generally-accepted generic PWITD statute, one that required the defendant know that he or she possessed an illegal substance.

The Supreme Court didn’t buy it. Instead, the Justices unanimously sided with the government’s view, that the a court should simply ask whether the prior state offense’s elements “necessarily entail one of the types of conduct” identified in the statute. In other words, the terms ““manufacturing, distributing, or possessing with intent to manufacture or distribute, a controlled substance” described conduct, not elements. It does not matter how many possible ways there might be to violate the state statute, nor does it matter whether other elements were present or lacking. If the defendant’s conduct was one of the listed terms, the prior felony was a “serious drug offense.”

(For what it’s worth, the Court’s opinion disputed Eddie’s contention that the Florida statute lacked a mens rea element, but the unanimous decision focused on the “conduct vs. elements” debate, not about the intricacies of the Florida statute.)

The decision is a disappointment for people who hoped the decision would do for ACCA people with drug priors what Taylor and Mathis did for crimes of violence. Leah Litman, a law professor at University of California – Irvine, wrote in SCOTUSBlog that the Shular decision “confirms two realities of the court’s docket. The first is the ease with which the court finds unanimity in ruling against criminal defendants; the second is the sprawling reach of federal criminal law, particularly with respect to drugs, guns and immigration.”

Shular v. United States, 2020 U.S. LEXIS 1366 (Supreme Ct. Feb. 26, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root