We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

THE WEEK IN COVID-19 LITIGATION

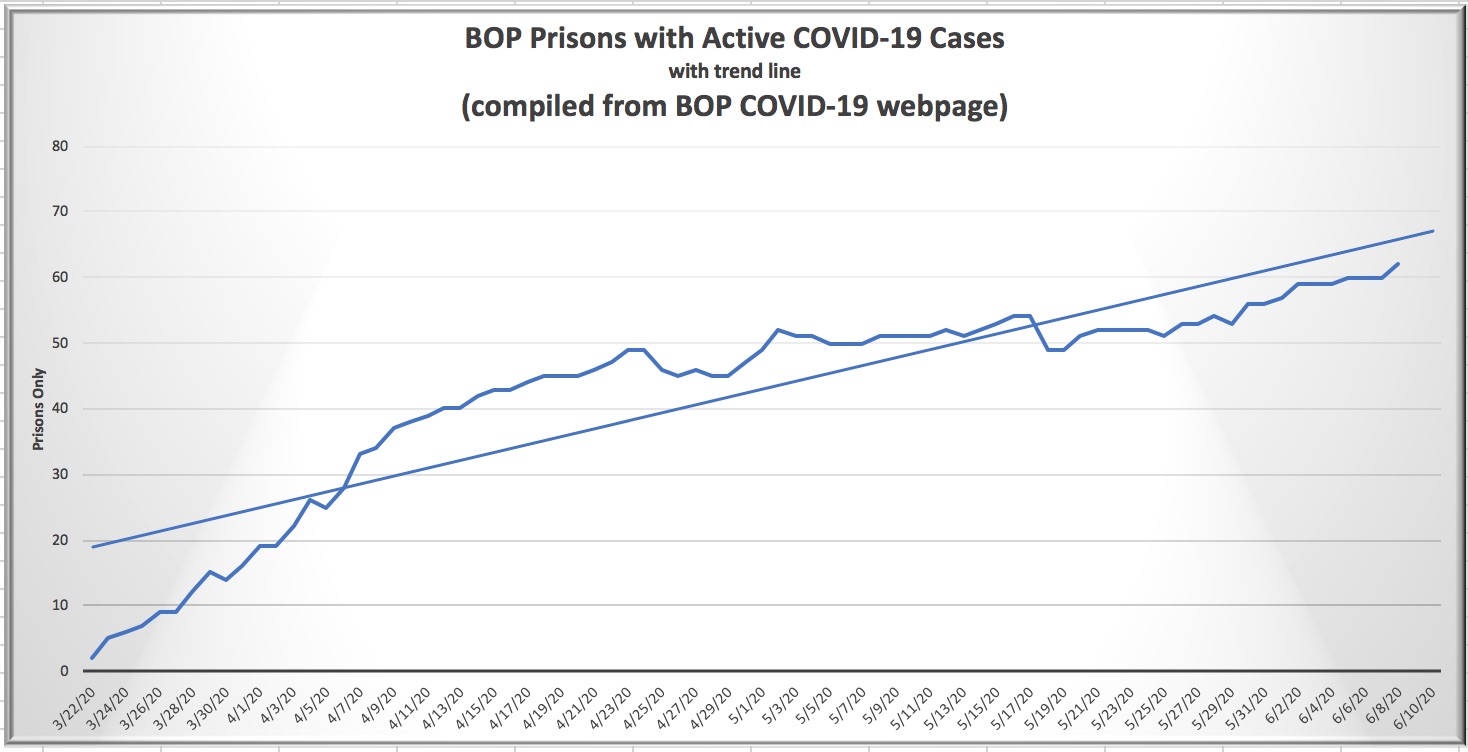

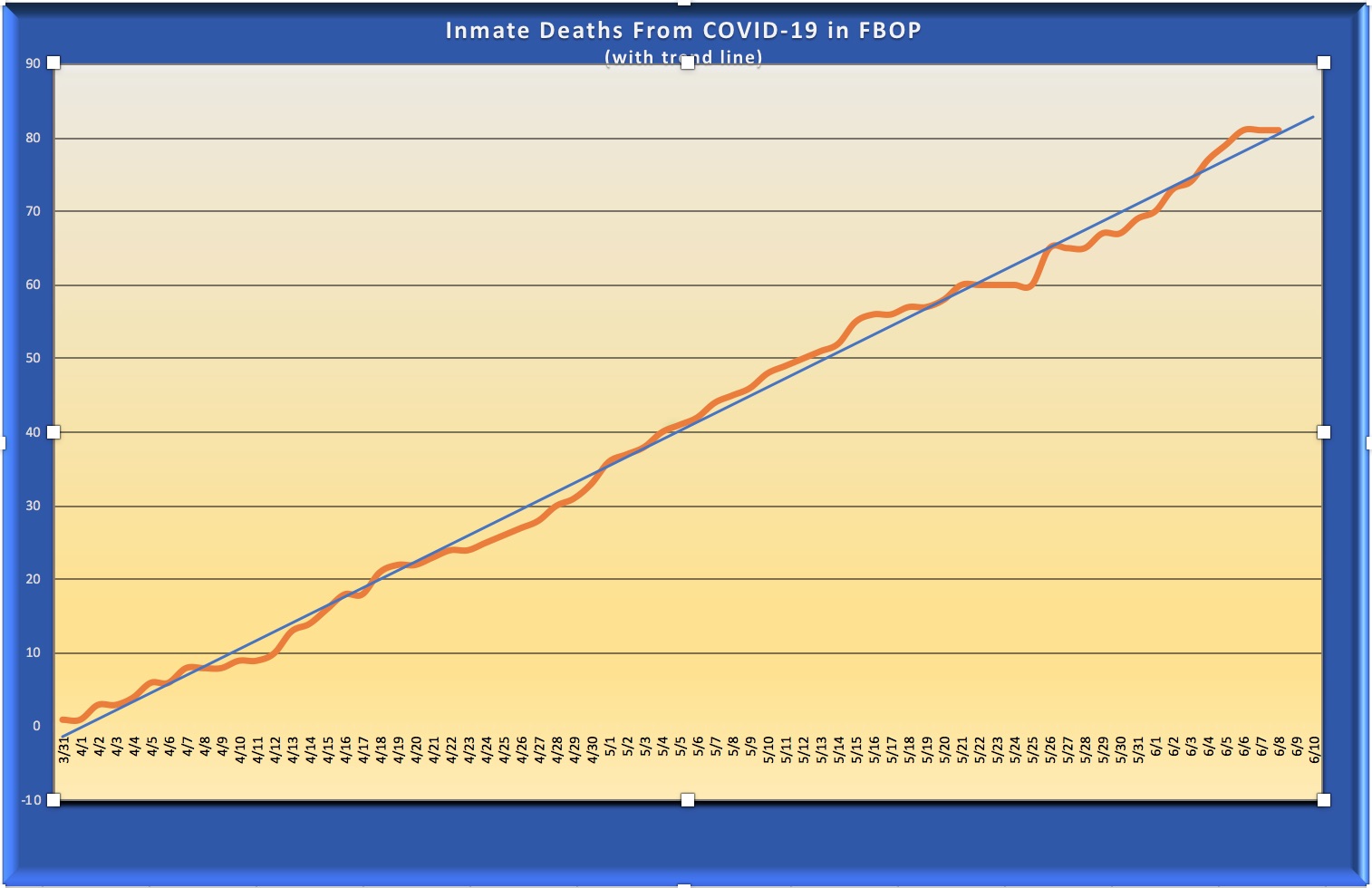

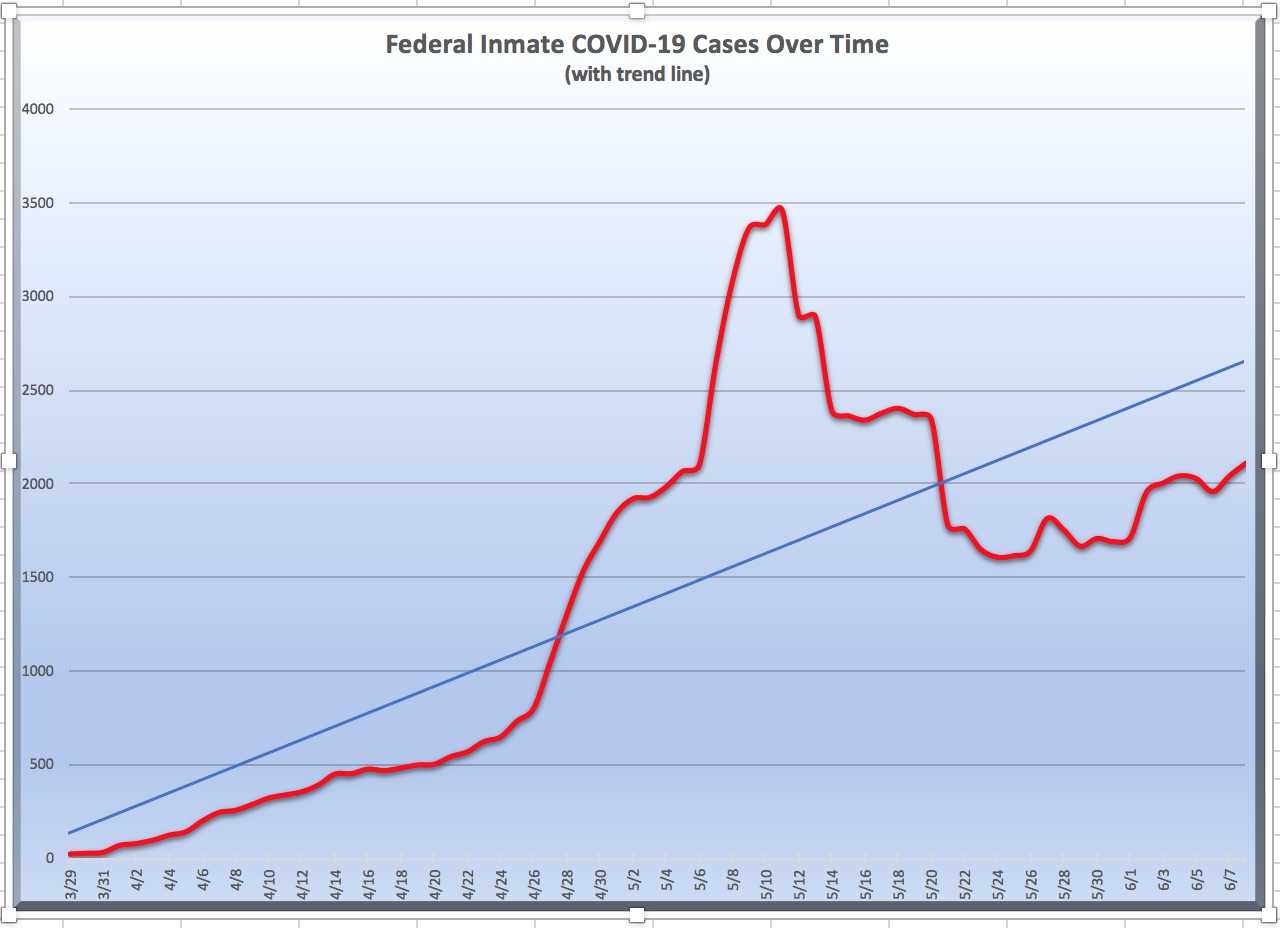

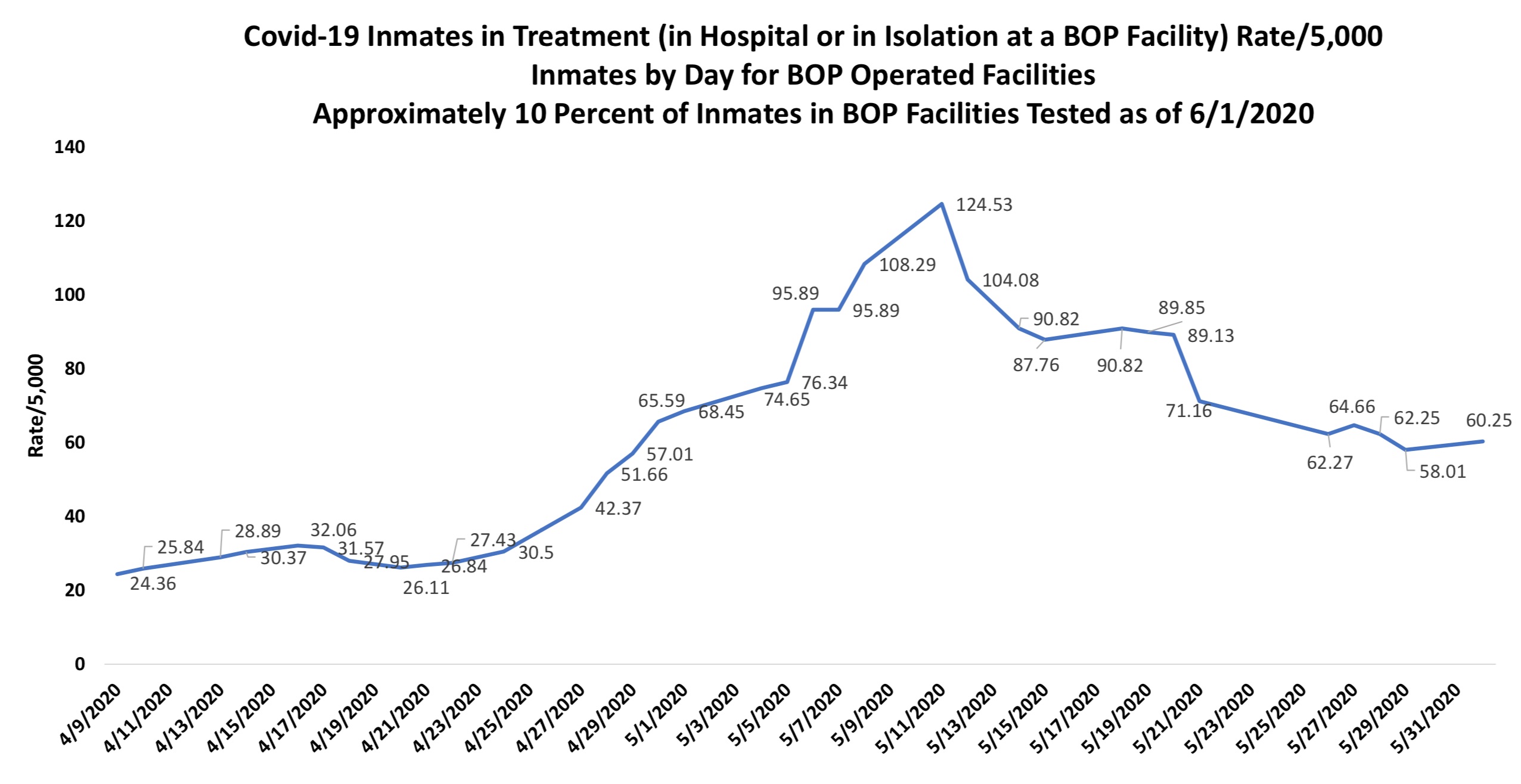

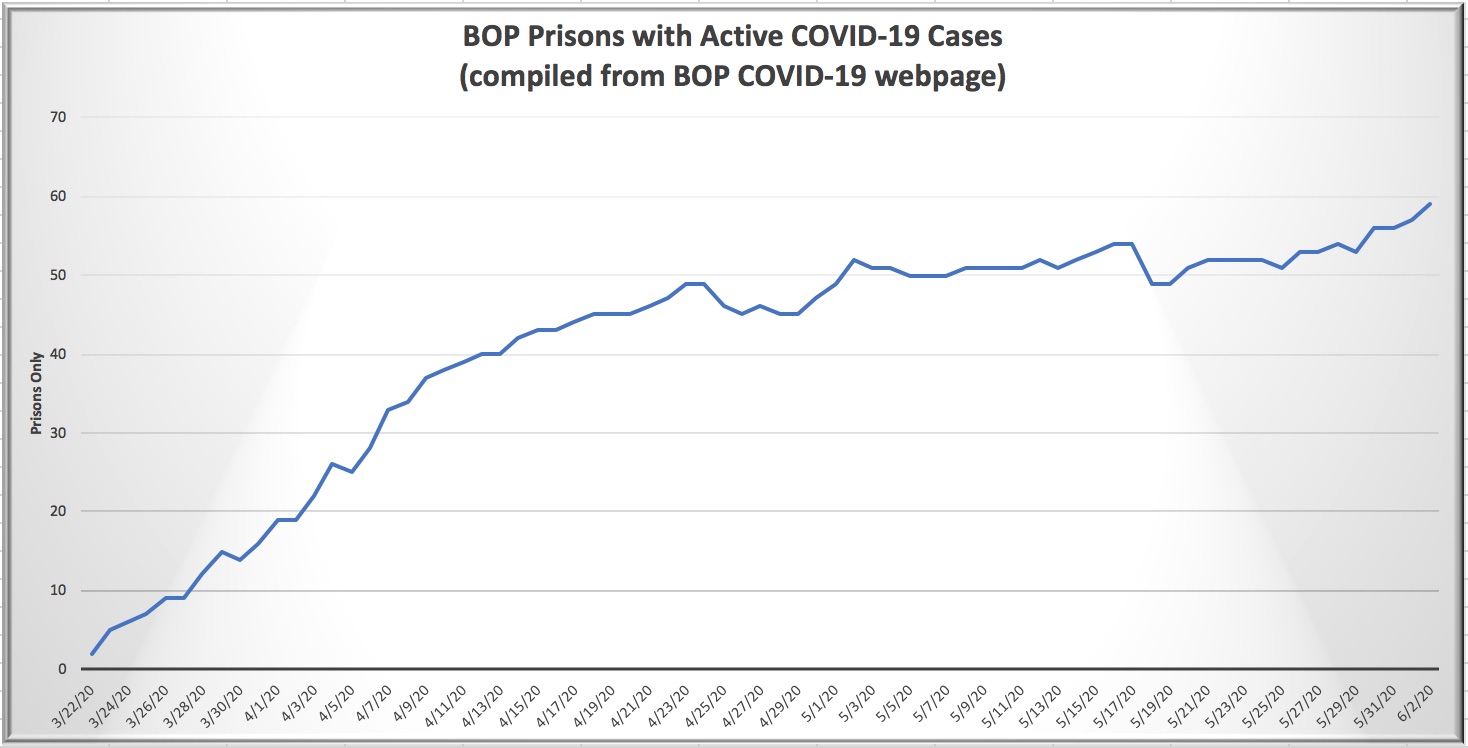

As of last night, June 14th, the number of Federal Bureau of Prisons inmates with COVID-19 had dropped from 2,109 a week ago to 1,341. The number of BOP facilities with COVID-19 on premises rose from 62 to 65, and then fell back to 62 as of last night. Deaths continued to climb, however, from 81 a week ago to 87 last night.

As of last night, June 14th, the number of Federal Bureau of Prisons inmates with COVID-19 had dropped from 2,109 a week ago to 1,341. The number of BOP facilities with COVID-19 on premises rose from 62 to 65, and then fell back to 62 as of last night. Deaths continued to climb, however, from 81 a week ago to 87 last night.

The numbers aren’t bad for the BOP. Inmate sickness has been fluctuating between 1,300 and 2,100 for a few weeks, and the number of prisons affected has leveled. But the BOP’s big advances last week were in the courtroom, not the medical suite.

Besides the 6th Circuit’s stay in FCI Elkton litigation, last Tuesday, Judge Rachel P. Kovner of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York denied prisoners a preliminary injunction because of inept medical care they claim amounts to cruel and unusual punishment, reasoning that despite deficiencies in MDC Brooklyn’s COVID-19 response, officials likely did not act with “deliberate indifference” to the health threat.

“Petitioners have not shown a clear likelihood that MDC officials have acted with deliberate indifference to substantial risks in responding to COVID-19,” Judge Kovner ruled. “Rather than being indifferent to the virus, MDC officials have recognized COVID-19 as a serious threat and responded aggressively.”

Nevertheless, the court cited significant problems with the BOP’s response to the pandemic. In particular, the judge noted the prison was way too slow responding to sick-calls requests and generally failed to isolate symptomatic inmates. “The MDC appears not to be isolating individuals who report COVID-19 symptoms,” in “tension with the CDC’s guidance” that they should be kept away from other inmates, Judge Kovner wrote. “Under standards of care that both parties have accepted, MDC officials’ apparent failure to fully implement the CDC guidance in these areas constitutes a deficiency in the MDC’s response to COVID-19.”

Judge Kovner also held the BOP had destroyed evidence by shredding the paper sick call requests used as the pandemic worsened. She sanctioned the BOP by drawing the inference that “the destroyed records would have contained additional reports of COVID-19 symptoms.” Still, the judge accepted the prison’s claims that it was doing the best it could under the circumstances, ruling that the evidence before the court did not clearly show that the inmates were at risk of serious harm, considering the MDC’s virus response, or that the prison did not care enough to shield them from that risk.

Judge Kovner also held the BOP had destroyed evidence by shredding the paper sick call requests used as the pandemic worsened. She sanctioned the BOP by drawing the inference that “the destroyed records would have contained additional reports of COVID-19 symptoms.” Still, the judge accepted the prison’s claims that it was doing the best it could under the circumstances, ruling that the evidence before the court did not clearly show that the inmates were at risk of serious harm, considering the MDC’s virus response, or that the prison did not care enough to shield them from that risk.

Meanwhile, last Thursday, a Massachusetts district court dealt a blow to the inmate habeas corpus/8th Amendment action against FMC Devens. The court held that the action – while calling itself a habeas corpus petition – was really a suit about prison conditions subject to the Prison Litigation Reform Act. The plaintiffs were given until the end of this week to show compliance with the PLRA, which mandates exhaustion of BOP administrative remedies as a jurisdictional condition. This holding conflicts with the 6th Circuit’s Wilson holding of three days before.

The North Carolina habeas corpus case against FCC Butner likewise suffered a setback on Thursday, when the Eastern District of North Carolina federal court denied a preliminary injunction. Like the 6th Circuit in the Elkton case, the district court ruled that while the inmate plaintiffs met the objective prong of the deliberate indifference showing, by showing that COVID-19 “poses significant health risks to both the world and community at large” and that the “disease’s uncontrolled spread within FCC Butner therefore presents a substantial risk of serious or substantial physical injury resulting from the challenged conditions,” they had not shown that the BOP was ignoring the spread of the illness.”

The North Carolina habeas corpus case against FCC Butner likewise suffered a setback on Thursday, when the Eastern District of North Carolina federal court denied a preliminary injunction. Like the 6th Circuit in the Elkton case, the district court ruled that while the inmate plaintiffs met the objective prong of the deliberate indifference showing, by showing that COVID-19 “poses significant health risks to both the world and community at large” and that the “disease’s uncontrolled spread within FCC Butner therefore presents a substantial risk of serious or substantial physical injury resulting from the challenged conditions,” they had not shown that the BOP was ignoring the spread of the illness.”

Chunn v. Edge, Case No. 20-cv-1590, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 100930 (E.D.N.Y., June 9, 2020)

Grinis v. Spaulding, Case No. 1:20-cv-10738-GAO, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 103251 (D.Mass., June 11, 2020)

Hallinan v. Scarantino, Case No. 5:20hc2088, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 103409 (E.D.N.C., June 11, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root