We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

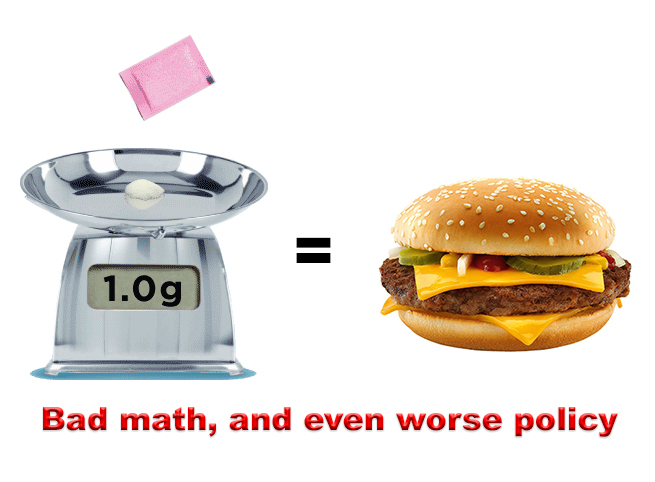

MYTHBUSTERS

Today, the LISA Newsletter began its 7th year of weekly publishing for federal inmates. Our first newsletter – sent on Sunday, November 29, 2015 – went to 13 inmates. Readership has grown a little since then: this week’s newsletter was sent last night to over 8,000 subscribers, both in and out of prison.

Today, the LISA Newsletter began its 7th year of weekly publishing for federal inmates. Our first newsletter – sent on Sunday, November 29, 2015 – went to 13 inmates. Readership has grown a little since then: this week’s newsletter was sent last night to over 8,000 subscribers, both in and out of prison.

At the same time, we have made over 1,125 posts, all of which – thanks to the miracle of the Internet – are available on this site.

To celebrate, I’m going to take today to bust some of the best inmate myths coming into my e-mailbag:

Question: Have you heard this 65% rumor that’s going around that Biden has supposedly signed into law and goes into effect at the beginning of next year? ~ JH

Answer: No, JH, not true. The “65% law” rumor has been around for as long as there have been sentencing guidelines. Before 1988, courts sentenced defendants to very general terms of years, often five years or 10 years. How long you actually served was up to the parole board. Under the parole board guidelines, you would do at least 1/3 but not more than 2/3 of your sentence. The exact point at which you would be paroled depended on the parole board guidelines, which were sort of like the current sentencing guidelines, although not nearly as detailed.

The 65% rumor may be based on the maximum amount of time (2/3) one would serve under an “old law” sentence. Starting in 2003, Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) introduced a bill at the beginning of each Congress to release certain federal inmates at 2/3 of their sentence. The bill would always be referred to the House Judiciary Committee, where it would die without ever being considered.

The 65% rumor may be based on the maximum amount of time (2/3) one would serve under an “old law” sentence. Starting in 2003, Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) introduced a bill at the beginning of each Congress to release certain federal inmates at 2/3 of their sentence. The bill would always be referred to the House Judiciary Committee, where it would die without ever being considered.

People who talk about how Congress should “bring back parole” suffer from a dangerous form of amnesia. The parole board was arbitrary and mean-spirited, providing minimal due process protections that make Guidelines sentencing look fair and loving by comparison. Currently, there is no “65% law” bill pending in Congress. Such a bill is unlikely ever to get serious consideration unless the guidelines are abandoned, and parole is reinstituted.

Question: We have heard the Federal Bureau of Prison Nonviolence Reform Act of 2021 passed both House and Senate about 5 days ago; is this true? This says you must have attained age 45, no violent charges, and no discipline at the institution. I hope it has passed both as my Mother said but nobody else’s family can find where it has passed. Did Mother “jump the gun”? ~ NP

Answer: Sorry, NP, Mom “jumped the gun.” This rumor blends some provisions of a couple of old bills introduced five years ago that never went anywhere and died at the end of the two-year Congress in which they were proposed. There are no such bills pending now, let alone being reported by House or Senate committees. And nothing is named the “Federal Bureau of Prison Nonviolence Reform Act of 2021″ or anything close to it.

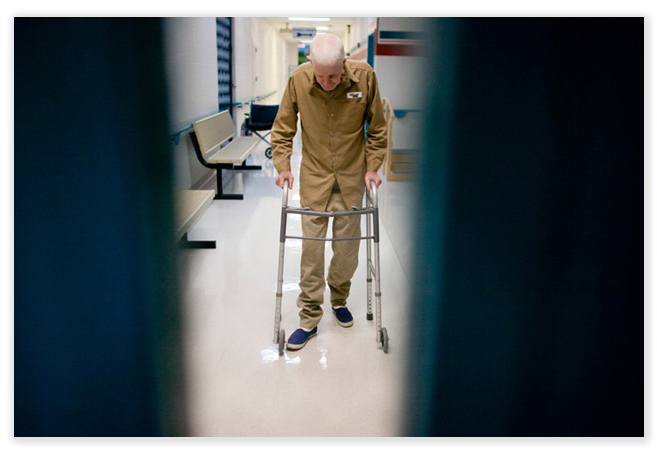

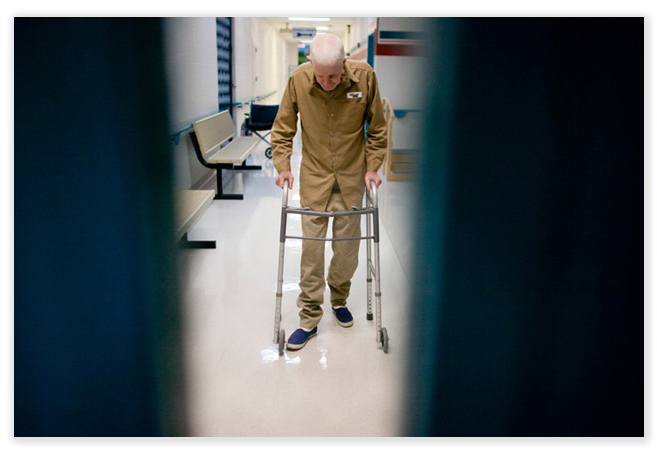

Question: I heard that an inmate was granted compassionate release but the prison somehow canceled it. I do not have the case number, however, I can give you the particulars of the case. The case was in 2003, in Central Islip, New York, and the defendant, Samuel Torres, was sentenced to 30 years in prison for drugs, weapons, and arson. If you could see why the motion was granted but then from what I hear, canceled… ~ RM

Answer: “Compassionate release” is the popular but misleading term for a sentence reduction under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i). It is a resentencing by the court. The BOP has no authority to “cancel” a sentence reduction by the court. The sentence is what the court says it is – not what the BOP may want it to be.

Answer: “Compassionate release” is the popular but misleading term for a sentence reduction under 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i). It is a resentencing by the court. The BOP has no authority to “cancel” a sentence reduction by the court. The sentence is what the court says it is – not what the BOP may want it to be.

(By the way, the case you referred me to does not exist).

Questions: I’ve been hearing that Biden is talking about giving us inmates up to a year off for Covid. Is there any truth to that at all? ~ MS

Questions: I’ve been hearing that Biden is talking about giving us inmates up to a year off for Covid. Is there any truth to that at all? ~ MS

Is there any truth to this gossip about people locked up during covid will get 10-18 months off their sentence?? ~ ML

Hello, have you heard anything about non-violent offenders getting an 18-month time cut for the pandemic? ~ AC

Answer: Biden has said nothing of the such. No one else has said anything of the such. The COVID-19 Safer Detention Act (S.312 and H.R. 3669), pending in both the House and Senate, have been favorably reported by the respective Judiciary Committees, but neither has come to a floor vote. Skopos Labs – which handicaps legislation – gives the bills only a 3% chance of passing.

The bills change the Elderly Offender Home Detention (EOHD) program to make people 60 or older eligible when they have served 2/3 of their good-time adjusted sentence, not their total sentence. The bills also give people turned down for EOHD placement the right to ask a court for that placement instead, much like compassionate release works now, and requires during the pandemic that any inmate with a COVID risk factor be deemed to have an extraordinary and compelling reason for a sentence reduction under 18 USC 3582(c)(1)(A)(i). Finally, the bills cut the exhaustion waiting period from 30 to 10 days as long as the pandemic emergency lasts.

The bills change the Elderly Offender Home Detention (EOHD) program to make people 60 or older eligible when they have served 2/3 of their good-time adjusted sentence, not their total sentence. The bills also give people turned down for EOHD placement the right to ask a court for that placement instead, much like compassionate release works now, and requires during the pandemic that any inmate with a COVID risk factor be deemed to have an extraordinary and compelling reason for a sentence reduction under 18 USC 3582(c)(1)(A)(i). Finally, the bills cut the exhaustion waiting period from 30 to 10 days as long as the pandemic emergency lasts.

No one proposes cutting sentences across the board because of COVID.

Question: I have heard about a reform bill that is supposed to have a 2-point reduction for federal inmates and/or mandatory minimums going down. Please tell me there is truth to this.

Question: I have heard about a reform bill that is supposed to have a 2-point reduction for federal inmates and/or mandatory minimums going down. Please tell me there is truth to this.

Answer: Only sort of. S.1014 – the First Step Implementation Act of 2021 – has been reported to the Senate floor by the Judiciary Committee. The bill would make the reductions in mandatory minimums for drug and gun offenses granted in § 401 and 403 of the First Step Act retroactive. This would let people with life or 20-year mandatory sentences under 21 USC § 841(b)(1)(A) move for a reduction of sentence, as well as people with stacked 18 USC § 924(c) sentences, seek reductions from their sentencing judges using the same mechanism as the crack defendants used under First Step Section 404.

Remember that a 2-point reduction in the Guidelines is made by the Sentencing Commission, not by statute, so such a change would come from the Sentencing Commission. The Sentencing Commission, now down to a single member, has not had a quorum to enable it to meet since First Step passed in 2018.

Question: When will the Senate vote on the EQUAL Act?

Question: When will the Senate vote on the EQUAL Act?

Answer: The EQUAL Act, which reduces crack cocaine penalties to be the same as powder cocaine penalties, passed the House of Representatives on Sept 28. However, there is no requirement that the Senate act on a bill passed by the House at any certain time, or even at all.

Answer: The EQUAL Act, which reduces crack cocaine penalties to be the same as powder cocaine penalties, passed the House of Representatives on Sept 28. However, there is no requirement that the Senate act on a bill passed by the House at any certain time, or even at all.

The Senate only has 10 more work days left this year. With the battle over Biden’s $2 trillion Build Back Better bill, just passed by the House, now looming in the Senate, the chance any criminal justice bill will be voted on this year is highly remote.

S. 312 – COVID-19 Safer Detention Act

H.R. 3669 – COVID-19 Safer Detention Act

S.1014 – First Step Implementation Act of 2021

H.R. 1693 – EQUAL Act

– Thomas L. Root

With only a handful of legislative days left this year, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) is demanding that the chamber pass the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), a federal budget, a debt-ceiling increase, and the Build Back Better Act before Christmas. There’s no room in Santa’s bag for any criminal justice reform with that very ambitious agenda.

With only a handful of legislative days left this year, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) is demanding that the chamber pass the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), a federal budget, a debt-ceiling increase, and the Build Back Better Act before Christmas. There’s no room in Santa’s bag for any criminal justice reform with that very ambitious agenda. Schumer and Booker had already said they want to hold off on the banking measure until Congress passes the more comprehensive reform. Wyden said last week the trio hasn’t shifted from their position. “We’re going to keep talking, but Sen. Schumer, Sen. Booker, and I have agreed that we’ll stay this course,” Wyden said last Monday. “The federal government has got to end this era of reefer madness.”

Schumer and Booker had already said they want to hold off on the banking measure until Congress passes the more comprehensive reform. Wyden said last week the trio hasn’t shifted from their position. “We’re going to keep talking, but Sen. Schumer, Sen. Booker, and I have agreed that we’ll stay this course,” Wyden said last Monday. “The federal government has got to end this era of reefer madness.” In September, Grassley told reporters he was doubtful eliminating the sentencing disparity would fly in the Senate. “I think there’s a possibility of reducing the 18 to 1 differential we have now,” he said, “but I don’t think one-to-one can pass.”

In September, Grassley told reporters he was doubtful eliminating the sentencing disparity would fly in the Senate. “I think there’s a possibility of reducing the 18 to 1 differential we have now,” he said, “but I don’t think one-to-one can pass.”