We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

OBJECTING FAST AND FURIOUSLY

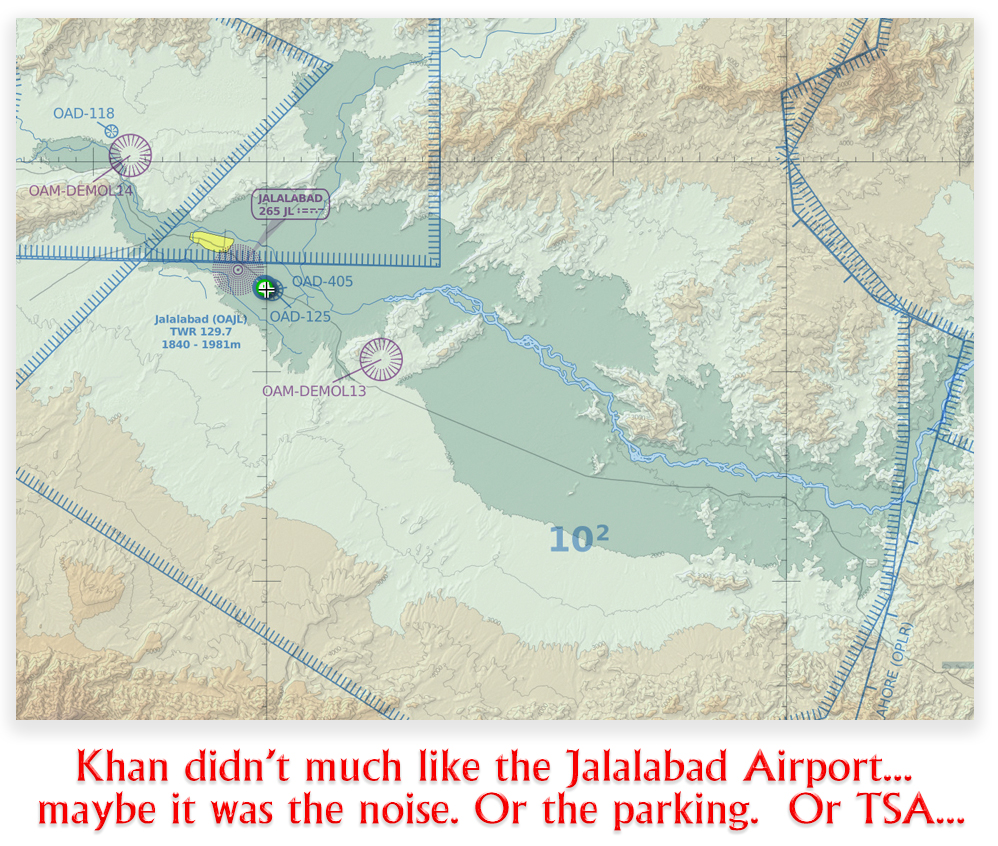

Over ten years ago, a couple of Taliban expatriates living in Pakistan joined a plot to drop some missiles into an eastern Afghanistan airfield. They connected with the mastermind, who lived in a dusty village near the Jalalabad target. As sometimes happens in plots, one of the expats, Jaweed, fell out with the other two conspirators, and reported the plan to local police. The Afghan cops turned it over to the U.S. DEA, who convinced Jaweed to go ahead with the plan while wearing a wire.

Over ten years ago, a couple of Taliban expatriates living in Pakistan joined a plot to drop some missiles into an eastern Afghanistan airfield. They connected with the mastermind, who lived in a dusty village near the Jalalabad target. As sometimes happens in plots, one of the expats, Jaweed, fell out with the other two conspirators, and reported the plan to local police. The Afghan cops turned it over to the U.S. DEA, who convinced Jaweed to go ahead with the plan while wearing a wire.

Hearing recordings of Khan’s plans and his boasts about the attack, the DEA decided to arrest him as soon as Jaweed gave him the missiles. Cooler heads prevailed, suggesting the missiles could unexpectedly do a “Fast and Furious,” and disappear before the arrest was carried out. So the DEA got Jaweed to arrange an opium buy using Khan as a broker. Khan said his commission would be used to buy a car to haul the missiles he expected to get. A heroin buy followed the opium deal, with Jaweed telling Khan all of the dope was going to the U.S. Khan seemed all right with this, saying, “Good, may God turn all the infidels to dead-corpses.”

Hearing recordings of Khan’s plans and his boasts about the attack, the DEA decided to arrest him as soon as Jaweed gave him the missiles. Cooler heads prevailed, suggesting the missiles could unexpectedly do a “Fast and Furious,” and disappear before the arrest was carried out. So the DEA got Jaweed to arrange an opium buy using Khan as a broker. Khan said his commission would be used to buy a car to haul the missiles he expected to get. A heroin buy followed the opium deal, with Jaweed telling Khan all of the dope was going to the U.S. Khan seemed all right with this, saying, “Good, may God turn all the infidels to dead-corpses.”

Suspecting that Kahn might not be fond of the U.S. or its citizens, a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C., indicted Khan for narcoterrorism and distributing drugs to be imported to the U.S. By the end of 2007, Khan found himself locked up in D.C. awaiting trial.

Fast forward furiously a decade: Khan finds himself doing life in the California high desert (must seem like home to him), but his case continues to twist and turn through the courts. Last Friday, the D.C. Circuit, in a remarkable decision that addresses in detail a defense attorney’s duty to investigate and object at trial – even when his client is obstinate, unhelpful and a schmuck – remanded the narcoterrorism charge to the trial court because of his lawyer’s ineffectiveness at trial.

Khan had been to the D.C. Circuit on direct appeal once before, where his sentence and conviction were affirmed, but the case was sent back for an evidentiary hearing on his claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. This time, the Circuit held “the performance of Mohammed’s trial counsel was constitutionally deficient… [because he] failed to investigate the possibility of impeaching the government’s central witness [Jaweed] as biased against Mohammed, despite ample indication that he should and could do so.” While the ineffectiveness did not prejudice the drug trafficking charge, the Circuit said, “as to the narcoterrorism charge, we cannot on this record confidently assess prejudice, and therefore remand to the district court for further proceedings on that issue.”

Defense attorneys sometimes have trouble getting people from across town to show up to testify. So you can sympathize with Khan’s attorney, who two months before trial told district court that he intended to seek witnesses in Afghanistan on Khan’s behalf, but noted that there were “very difficult obstacles in terms of finding witnesses, locating them, and then somehow bringing them to the United States under some type of parole visas.” On the eve of trial, the attorney confirmed that he “did look into … how do you even get [to Afghanistan], and who [from the office] was I going to take,” but there were “no volunteers.” Hard to believe, huh?

Defense attorneys sometimes have trouble getting people from across town to show up to testify. So you can sympathize with Khan’s attorney, who two months before trial told district court that he intended to seek witnesses in Afghanistan on Khan’s behalf, but noted that there were “very difficult obstacles in terms of finding witnesses, locating them, and then somehow bringing them to the United States under some type of parole visas.” On the eve of trial, the attorney confirmed that he “did look into … how do you even get [to Afghanistan], and who [from the office] was I going to take,” but there were “no volunteers.” Hard to believe, huh?

Ultimately, Khan’s lawyer conceded that he failed to “follow through” on his previously expressed intent to contact witnesses in Afghanistan. Although the government provided a contact list from Khan’s phone book in discovery, defense counsel never attempted to call any potential witnesses in Afghanistan and, in fact, even mistakenly told the court he “wasn’t given telephone numbers.” Khan told the court he had “asked [counsel] to bring my witnesses,” and specifically identified four witnesses who would say that he was not associated with the Taliban. Counsel admitted this, but apparently thought the only way he could interview the potential witnesses would have been to travel to Afghanistan, which he concluded posed “insurmountable” difficulties.

The problem, simply enough, was far from simple. It turns out that a substantial number of Afghanis hate us. And hate the Russians. And the British. And different tribes. And each other. In Khan’s case, he and Jaweed were from the same village and had known each other for a long time. At one point, Jaweed’s mom asked Khan if he would allow Jaweed to marry Khan’s sister. Khan said no. Khan and Jaweed were later in a lawsuit against each other. Khan beat Jaweed’s cousin in an election. There was, as they say, a lot of bad blood between them.

The government’s case against Khan relied on Jaweed’s recorded undercover conversations with him, and Jaweed’s own testimony, which addressed the meaning of those conversations and, more broadly, the two men’s interactions. Defense counsel called Jaweed’s testimony “the bread and butter of the case.” The government repeatedly asked Jaweed to clarify the meaning of exchanges, and Jaweed obliged some 118 times. It was obvious to anyone that Jaweed’s credibility was crucial to the government’s case.

The Circuit, noting that “complete failure to investigate potential impeachment witnesses cannot be construed as a strategic decision on the part of defense counsel,” found that counsel knew Jaweed’s testimony would be central to the upcoming trial, and even took preliminary steps to understand Jaweed’s background, including asking the government to search for any official criminal records. “But he did not investigate the possibility of Jaweed’s bias, despite knowing about” the election.

The Circuit, noting that “complete failure to investigate potential impeachment witnesses cannot be construed as a strategic decision on the part of defense counsel,” found that counsel knew Jaweed’s testimony would be central to the upcoming trial, and even took preliminary steps to understand Jaweed’s background, including asking the government to search for any official criminal records. “But he did not investigate the possibility of Jaweed’s bias, despite knowing about” the election.

The Circuit disagreed with the trial court that counsel had no duty to investigate whether Jaweed was biased against Khan “when the only information he had about this purported bias was the election.” The appellate panel said, “Any information about potential sources of bias in a witness as crucial as Jaweed should have led to further investigation… The district court appears to have concluded that counsel could not be expected to take investigative steps that Mohammed did not specifically suggest to him. But even when defendants are fatalistic or uncooperative, that does not obviate the need for defense counsel to conduct some sort of … investigation. Indeed, when defendants are actively obstructive, they remain entitled to effective counsel. Counsel has a duty to investigate, even if his or her client does not divulge relevant information.”

The Circuit disagreed with the trial court that counsel had no duty to investigate whether Jaweed was biased against Khan “when the only information he had about this purported bias was the election.” The appellate panel said, “Any information about potential sources of bias in a witness as crucial as Jaweed should have led to further investigation… The district court appears to have concluded that counsel could not be expected to take investigative steps that Mohammed did not specifically suggest to him. But even when defendants are fatalistic or uncooperative, that does not obviate the need for defense counsel to conduct some sort of … investigation. Indeed, when defendants are actively obstructive, they remain entitled to effective counsel. Counsel has a duty to investigate, even if his or her client does not divulge relevant information.”

The Court of Appeals also found that defense counsel failed by not objecting to Jaweed’s frequent “interpretations” of his conversations with Khan. The Circuit said

a proficient attorney would have promptly objected and, once it became clear the government would repeatedly solicit Jaweed’s testimony about Mohammed’s state of mind, lodged a standing objection. Had Jaweed’s entire testimony been confined to what Jaweed understood, not what Mohammed meant—as the district court ultimately suggested it should be —the jury likely would have better appreciated the limitations of that testimony. Had Mohammed’s counsel also independently sown doubt as to Jaweed’s credibility, the subtle distinction between Jaweed’s actual testimony (about Mohammed’s state of mind) and testimony to which Jaweed should have been confined (about what he understood Mohammed to mean) could have been significant. Thus, the failure to object to Jaweed’s interpretations should be considered part and parcel of counsel’s failure generally to undermine Jaweed’s testimony.

The Circuit noted that the prejudice question hinged on whether Kahn “has shown a reasonable probability that adequate investigation would have enabled trial counsel to sow sufficient doubt about Jaweed’s credibility to sway even one juror.” The recordings about drugs spoke for themselves, the court said, but because Jaweed’s spinning of the equivocal statements on the recordings was the only evidence of narcoterrorism, the case was remanded for the district court to try to figure out what defense counsel would have uncovered in 2008 had he only looked for it.

The Circuit noted that the prejudice question hinged on whether Kahn “has shown a reasonable probability that adequate investigation would have enabled trial counsel to sow sufficient doubt about Jaweed’s credibility to sway even one juror.” The recordings about drugs spoke for themselves, the court said, but because Jaweed’s spinning of the equivocal statements on the recordings was the only evidence of narcoterrorism, the case was remanded for the district court to try to figure out what defense counsel would have uncovered in 2008 had he only looked for it.

United States v. Mohammed, Case No. 16-3102 (D.C. Cir., July 21, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root