We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

SAVING DAN MCCARTHAN

In the world of habeas corpus, federal defendants quickly are on first-name basis with Title 28, Section 2255, of the United States Code. Soon, a substantial number may as well known the name “Dan McCarthan.”

First, some background: The right of habeas corpus is shorthand for “Habeas corpus ad subjiciendum,” meaning roughly “that you have the person for the purpose of subjecting him/her to examination,” the first sentence of the writ issued by the court.

First, some background: The right of habeas corpus is shorthand for “Habeas corpus ad subjiciendum,” meaning roughly “that you have the person for the purpose of subjecting him/her to examination,” the first sentence of the writ issued by the court.

The great English commentator on the law, Lord William Blackstone, called writ of habeas corpus has been called “the great and efficacious writ in all manner of illegal confinement.” At its essence, the writ of habeas corpus is a court order addressed to a prison official that demands a prisoner be brought before the court and that the custodian present proof of authority to detain him. It allows the court to determine whether the prison authority has lawful authority to detain the prisoner in the conditions in which he is detained. If the custodian is acting beyond his or her authority, then the prisoner must be released.

Some say habeas corpus originated with the Magna Carta’s guarantee that no freeman could lose his liberty or property except by the law of the land (sounding a lot like the 5th Amendment’s guarantee of due process). Others trace it to the Assize of Clarendon, a re-issuance of rights during the reign of Henry II of England about 50 years before the Magna Carta. Lord Blackstone cited the first recorded issuance of a writ of habeas corpus ad subjiciendum in 1305.

Regardless of when it first was enshrined in English law, by the time the United States Constitution was drafted, habeas corpus was assumed to be the law, so much so that the Constitution only guarantees it in the negative, that is, “[t]he privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.”

The privilege may not be easily suspended, but Congress and courts have shown that it can be easily regulated. Habeas corpus for federal prisoners is controlled by Sec. 2255 (which permits and regulates post-conviction motions attacking the lawfulness of convictions and sentences) and 28 USC 2241 (habeas corpus for conditions of confinement). For prisoners seeking to get out of prison, 2255 is the only game in town.

The privilege may not be easily suspended, but Congress and courts have shown that it can be easily regulated. Habeas corpus for federal prisoners is controlled by Sec. 2255 (which permits and regulates post-conviction motions attacking the lawfulness of convictions and sentences) and 28 USC 2241 (habeas corpus for conditions of confinement). For prisoners seeking to get out of prison, 2255 is the only game in town.

Restricting prisoners’ rights to challenge their convictions is a pretty easy issue to demagogue. No one likes prisoners, and Congress has given legislative voice to public disdain for convicts by restricting when and how Section 2255 may be used. A prisoner has only one year from finality of the conviction to challenge it, subject only to strictly limited exceptions. Like dogs, every inmate gets only one bite: filing a second 2255 motion requires prior approval of a court of appeals, which is granted only in the most limited circumstances. Only where new facts that could not have been discovered before and convincingly prove innocence, or a new Supreme Court ruling changing a constitutional rule and made retroactive, can a prisoner file a second 2255 motion.

The holding in Johnson v. United States, where a part of the Armed Career Criminal Act was declared unconstitutionally vague, is the most recent example of a retroactive holding. Such decisions are never declared retroactive in the holding itself: rather, a case is declared to be retroactive in a subsequent decision that addresses specifically the retroactivity of the prior case.

This two-step procedure can be perilous. Sec. 2255 only provides one year from a new Supreme Court case to file any new claims. Often, however, it takes that long or longer to get a retroactivity ruling from the Supreme Court. In Johnson’s case, the holding came with only two months to go. Sometimes, the holding comes after the deadline altogether.

A different but more serious problem comes when changes in the law are not based on the constitution. In 1995, the Supreme Court decided that the lower courts had been misinterpreting 18 USC 924(c) – which punishes using a gun in a crime of violence or drug offense – and locking up many people to whom the statute did not apply. The decision was purely one of statutory interpretation, with no constitutional dimension whatsoever. Under the law, people who had already filed a 2255 motion could not file another one, because the change in the law did not qualify them for permission from a court of appeals for a second 2255.

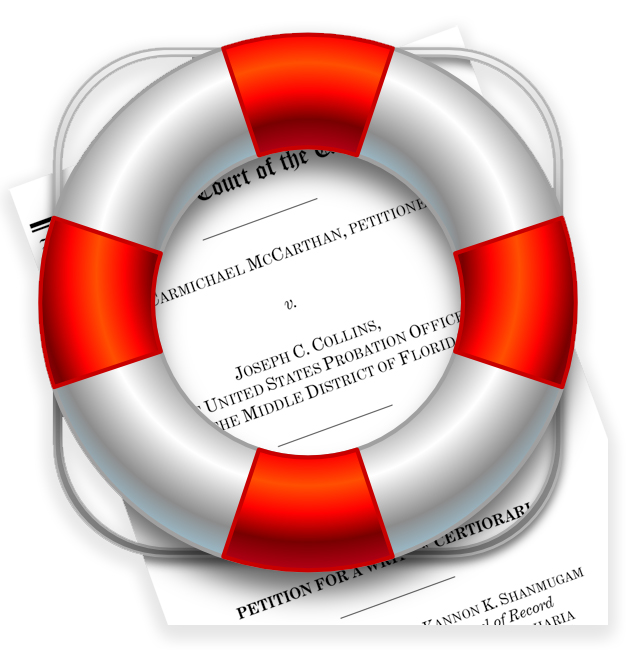

For that kind of problem, 2255 has a “saving clause” at 28 USC 2255(e), which provides that a prisoner may not use the other form of federal habeas corpus – a petition under 28 USC 2241 –instead of a 2255 “unless it also appears that the remedy by [2255] motion is inadequate or in-effective to test the legality of his detention.”

Dan McCarthan Needs a Lifeline: For the past 20 years, courts have let prisoners use 2241 to challenge convictions that suddenly became non-convictions because statutes had been reinterpreted in such a way that the inmates were no longer guilty of a crime. And what could make more sense? If a guy has been locked up for a decade, and he already used up and lost his 2255 nine years before, does that make it fair to keep him in prison another 10 years for something that’s no longer a crime?

Dan McCarthan Needs a Lifeline: For the past 20 years, courts have let prisoners use 2241 to challenge convictions that suddenly became non-convictions because statutes had been reinterpreted in such a way that the inmates were no longer guilty of a crime. And what could make more sense? If a guy has been locked up for a decade, and he already used up and lost his 2255 nine years before, does that make it fair to keep him in prison another 10 years for something that’s no longer a crime?

Dan McCarthan didn’t think so. Years before, Dan had walked away from a halfway house, a mistake that caught him an escape charge. When Dan was convicted federally of being a felon in possession of a gun, escape charges were deemed to be violent, and that qualified him for a mandatory 15-year sentence under the ACCA. But then, in 2009, the Supreme Court held escape was not a violent crime. Because the decision was based on interpreting the statute, and was not constitutional, it did not entitle Dan to file a second 2255. So he filed a 2241.

While the district court threw out Dan’s 2241, a three-judge panel on the 11th Circuit held he was entitled to use a 2241. But then, the Circuit decided to rehear Dan’s case en banc, and told the parties to brief the question of whether the 2241 could be used in this kind of case.

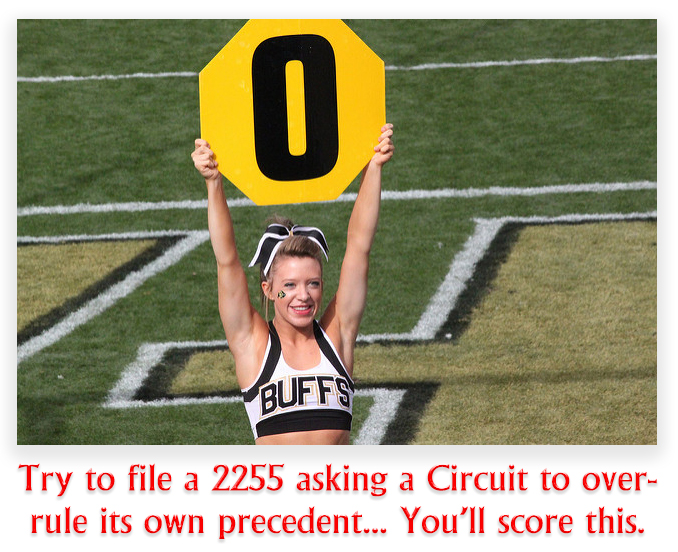

The government and Dan agreed that the 2241 was appropriate in this kind of case, but the Circuit – by a 7-4 vote last March, with six different opinions totaling more than 150 pages – held that an initial Section 2255 motion is an adequate and effective remedy to “test” a sentence, even when circuit precedent forecloses the movant’s claim at the time of the motion. After all, the Circuit said, a movant could have asked the court of appeals to overrule its precedent, sought Supreme Court review, or both. The en banc decision asserted the saving clause in Section 2255(e) is concerned only with ensuring that a person in custody has a “theoretical opportunity” to pursue a claim, even if, at the time of the initial 2255 motion, the claim was virtually certain to fail in the face of adverse precedent.

Prior to the 11th Circuits’s decision in Dan’s case, only the 10th Circuit took such a draconian view of the saving clause (in a decision written by Judge – now Justice – Neil Gorsuch). But now, the circuit split is 9-2, with thousands of federal inmates in Florida, Georgia and Alabama now shut out for relief.

Prior to the 11th Circuits’s decision in Dan’s case, only the 10th Circuit took such a draconian view of the saving clause (in a decision written by Judge – now Justice – Neil Gorsuch). But now, the circuit split is 9-2, with thousands of federal inmates in Florida, Georgia and Alabama now shut out for relief.

Fortunately, someone lined Dan up with Kannon Shanmugam, a former Antonin Scalia law clerk who is now a Supreme Court veteran. With 20 oral arguments under his belt, Kannon heads the Supreme Court practice for D.C. law powerhouse Williams & Connolly. It’s like Dan’s flag football team really needed a good quarterback, and Aaron Rodgers showed up. Sure, you can argue that there are several quarterbacks arguably better than Aaron, but he’s in anyone’s Top 5. So is Kannon.

Dan filed a petition for writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court two weeks ago, asking the Court to resolve the circuit split by ruling that the 2255 savings clause was intended to throw a lifeline to someone who never had a reasonable chance because circuit precedent foreclosed his argument. As the Seventh Circuit once explained it, with circuit precedent against a prisoner, “[t]he trial judge, bound by our… cases, would not listen to him; stare decisis would make us unwilling (in all likelihood) to listen to him; and the Supreme Court does not view itself as being in the business of correcting errors.” In those circumstances, the Seventh Circuit reasoned, Section 2255 “can fairly be termed inadequate,” because “it is so configured as to deny a convicted defendant any opportunity for judicial rectification of so fundamental a defect in his conviction as having been imprisoned for a nonexistent offense.”

Dan argues eloquently for the Supreme Court to hear the case:

The conflict on the question presented cries out for the Court’s intervention. The arguments on both sides of the conflict are well developed, with the benefit of numerous opinions across nearly every regional circuit over the last two decades. There is little room for the law to develop further. And this case is an apt vehicle for resolving the conflict, because the relevant arguments have been exhaustively presented in six separate opinions from an en banc court whose members embraced the full spectrum of positions on the question. This case satisfies all of the criteria for the Court’s review, and the petition for a writ of certiorari should therefore be granted.

This cert petition is very consequential to thousands of inmates, not just those who have suddenly found their statutes of conviction redefined to make them innocent, but for those who will in the future. If the 11th Circuit opinion spreads, it will – as Dan’s petition puts it – “close[] the door for collateral relief to any person whose conviction or sentence was rendered unlawful by Supreme Court precedent postdating an initial Section 2255 motion.”

This cert petition is very consequential to thousands of inmates, not just those who have suddenly found their statutes of conviction redefined to make them innocent, but for those who will in the future. If the 11th Circuit opinion spreads, it will – as Dan’s petition puts it – “close[] the door for collateral relief to any person whose conviction or sentence was rendered unlawful by Supreme Court precedent postdating an initial Section 2255 motion.”

The Supreme Court will probably resolve the petition for writ of cert by the end of the year.

McCarthan v. Collins, Case No. 17-85, Petition for Writ of Certiorari (July 12, 2017)

– Thomas L. Root

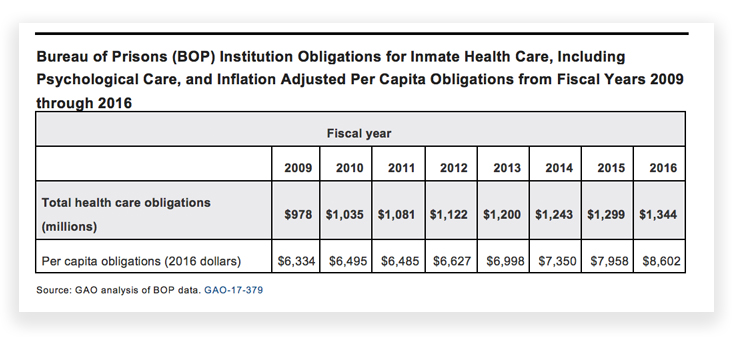

At the same time, Sessions is urging the commission to toughen sentences for certain violent criminals, drug offenders, illegal immigrant smugglers and so-called career offenders. In public comments filed with the Sentencing Commission on July 31, the Dept. of Justice asked it to preserve mandatory-minimum sentences that supporters say help fight crime but critics say inflate prison costs and disproportionately hurt minority communities without improving public safety.

At the same time, Sessions is urging the commission to toughen sentences for certain violent criminals, drug offenders, illegal immigrant smugglers and so-called career offenders. In public comments filed with the Sentencing Commission on July 31, the Dept. of Justice asked it to preserve mandatory-minimum sentences that supporters say help fight crime but critics say inflate prison costs and disproportionately hurt minority communities without improving public safety. DOJ also encouraged the Commission to abandon the categorical approach (Mathis v. United States) for determining which state crimes are crimes of violence supporting much higher sentencing ranges for “career offenders.” The Department complains that the “categorical approach,” which requires courts to “focus solely on whether the elements of the crime of conviction sufficiently match the elements of a generic version of the crime,” focuses on the abstract elements of the statute “and largely ignores the conduct that the defendant actually committed. This approach has resulted in some repeat violent offenders… receiving a sentencing range that is lower than their conduct and criminal history warrant. The categorical approach also consumes an inordinate amount of time for trial court judges, appellate court judges, probation officers, prosecutors, and defense attorneys.”

DOJ also encouraged the Commission to abandon the categorical approach (Mathis v. United States) for determining which state crimes are crimes of violence supporting much higher sentencing ranges for “career offenders.” The Department complains that the “categorical approach,” which requires courts to “focus solely on whether the elements of the crime of conviction sufficiently match the elements of a generic version of the crime,” focuses on the abstract elements of the statute “and largely ignores the conduct that the defendant actually committed. This approach has resulted in some repeat violent offenders… receiving a sentencing range that is lower than their conduct and criminal history warrant. The categorical approach also consumes an inordinate amount of time for trial court judges, appellate court judges, probation officers, prosecutors, and defense attorneys.” DOJ argues that “the time has come to abandon the categorical approach in those cases involving the enumerated felonies clause. The Department would be pleased to work with the Commission to develop a workable and fair approach that focuses less on formalism and more on the defendant’s conduct.”

DOJ argues that “the time has come to abandon the categorical approach in those cases involving the enumerated felonies clause. The Department would be pleased to work with the Commission to develop a workable and fair approach that focuses less on formalism and more on the defendant’s conduct.”