We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

DC CIRCUIT HOLDS THAT CHANGES IN THE LAW CANNOT SUPPORT COMPASSIONATE RELEASE

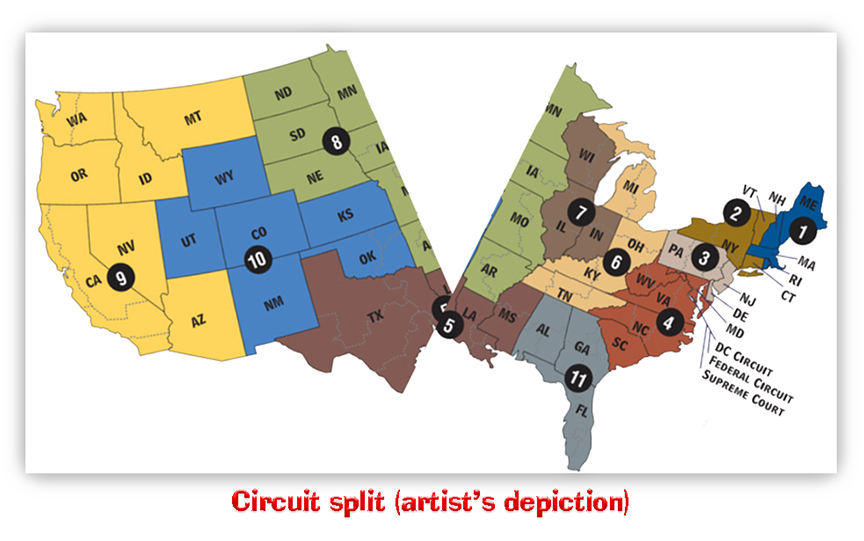

The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit has deepened the circuit split on compassionate release, joining three other circuits in holding that a prisoner cannot use the fact he or she is serving a sentence that could not be imposed today as “extraordinary and compelling” reason for an 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i) compassionate release.

The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit has deepened the circuit split on compassionate release, joining three other circuits in holding that a prisoner cannot use the fact he or she is serving a sentence that could not be imposed today as “extraordinary and compelling” reason for an 18 USC § 3582(c)(1)(A)(i) compassionate release.

In 2016, Curtis Jenkins was caught by D.C. police with drugs and a gun. He got bonded out of jail, but a short time later he was caught by D.C. police again with drugs and a gun. Curtis thus faced two 18 USC § 924(c) counts (for carrying a gun during drug trafficking) and a 15-year Armed Career Criminal Act count (18 USC § 924(e)), not to mention qualifying as a “career offender” under the Sentencing Guidelines (which dramatically jacks up the sentencing range).

Factor all of that into the mix, Curtis was looking at a minimum 45-year sentence. He did the wise thing, agreeing to a plea deal that carried a Guidelines range of 23-27 years. Despite that range – still a substantial chunk of time – The parties agreed to recommend only 12 years to the sentencing judge.

From there, things got even better. Curtis walked out of sentencing with eight years. For the math-challenged among us, good lawyering had cut Curtis’s sentence exposure by about 82%.

It looked like a great deal at the time, but after a few years, Curtis thought it had all turned to dust later.

First, in 2018, the First Step Act changed § 924(c) so that the 25-year add-on sentence required by law for the second § 924(c) violation would only apply if the second offense came after a first conviction. If that had been the law when Curtis was convicted, his 45-year mandatory minimum sentence would have been only 30 years.

Second, things changed for Curtis’s ACCA conviction. If a felon was caught with a gun back when Curtis was nabbed, he or she faced a zero-to-ten-year sentence. But if the defendant had three prior convictions for violent crimes or drug offenses, the sentence was a minimum 15 years. Two of Curtis’s predicate offenses qualifying him for the ACCA were for assault with a weapon. D.C. law at the time permitted conviction for that offense even when the assault was committed “recklessly.” But in 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Borden v. United States that any crime that could be committed recklessly was not a “crime of violence” for ACCA purposes. If that had been the law when Curtis was convicted, his 30-year mandatory minimum sentence exposure would have dropped to only 10 years.

Third, the Court of Appeals held in United States v. Winstead that drug offenses relied on to qualify someone as a Guidelines career offender could not count when they were mere attempts. Curtis’s drug priors were for attempted drug distribution, meaning that the high sentencing range that applied because he was a Guidelines “career offender” would have been out, too.

Like that, all of the very good reasons Curtis once had for taking a 12-year deal disappeared like Halloween candy on trick-or-treat night. He moved for a sentence reduction, arguing that if he had made a deal based on the sentence exposure he would have faced if he were sentenced today, it would have been a lot lower.

The district court denied Curtis’s

The district court denied Curtis’s

motion, holding that changes in the law were not the kind of “extraordinary and compelling” reasons for sentence reduction listed in USSG § 1B1.13, the Guidelines policy statement covering compassionate release motions. That statement does not bind the court, the judge ruled, but he nonetheless referred to it for “guidance.”

The district court said the First Step Act, Winstead, and Borden were irrelevant, because the compassionate-release statute does not permit courts to reexamine the lawfulness or fairness of a sentence as originally imposed.

Two weeks ago, the DC Circuit upheld the district court’s denial. “We agree with the 3rd, 7th, and 8th Circuits,” the appellate panel wrote. “To begin, there is nothing remotely extraordinary about statutes applying only prospectively. In fact, there is a strong presumption against statutory retroactivity, which is ‘deeply rooted in our jurisprudence’ and ‘embodies a legal doctrine older than our Republic’… [The Supreme Court has held that] in federal sentencing the ordinary practice is to apply new lower penalties to defendants not yet sentenced, while withholding that change from defendants already sentenced. And what “the Supreme Court views as the ‘ordinary practice’ cannot also be an ‘extraordinary … reason’ to deviate from that practice.”

But other Circuits – including the 2nd, 4th, 5th, 9th and 10th – do consider such changes to be among the “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for sentence reduction that will drive a compassionate release motion. The Circuit split just exacerbated by Curtis’s D.C. Circuit decision will most likely be fixed not by the Supreme Court but rather by the newly-reconstituted Sentencing Commission.

But other Circuits – including the 2nd, 4th, 5th, 9th and 10th – do consider such changes to be among the “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for sentence reduction that will drive a compassionate release motion. The Circuit split just exacerbated by Curtis’s D.C. Circuit decision will most likely be fixed not by the Supreme Court but rather by the newly-reconstituted Sentencing Commission.

The Commission, which just announced having received over 8,000 public comments on its announcement of proposed priorities – has its first public meeting set for this coming Friday. The Commission is expected to adopt its priorities for the coming year, the first of which is likely to be to amend § 1B1.13 to bring some predictability to compassionate release cases.

When that happens, § 1B1.13 will again be binding on the courts, and we can expect a little uniformity to be injected into what is now a chaotic compassionate release system.

United States v. Jenkins, Case No. 21-3089, 2022 U.S.App. LEXIS 28198 (D.C. Cir., Oct. 11, 2022)

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Public Meeting, October 28, 2022

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Public Comments on Priorities (October 23, 2022)

– Thomas L. Root