We post news and comment on federal criminal justice issues, focused primarily on trial and post-conviction matters, legislative initiatives, and sentencing issues.

WE MAY HAVE MISREAD THAT, THE COURT SAYS…

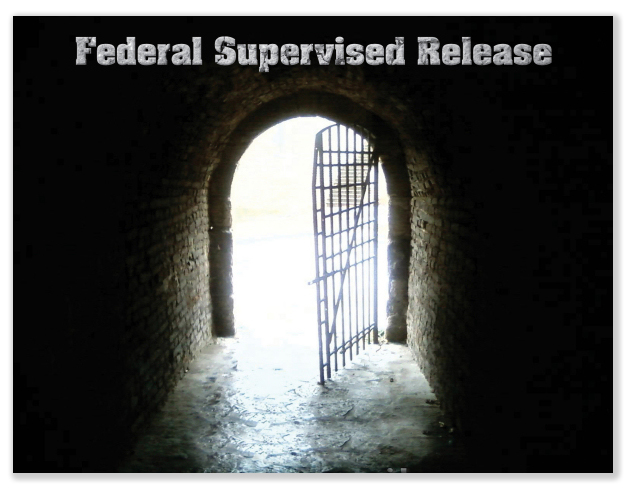

Supervised release is a period after a federal inmate completes his or her prison sentence – a lot like parole and kind of like probation – during he or she is subject to a series of reporting conditions and limitations imposed by the court. A U.S. Probation Officer supervises the former inmate, and holds the power to seek revocation of supervised release and return to prison under evidentiary and procedural standards that are rather lax, to say the least.

Supervised release is a period after a federal inmate completes his or her prison sentence – a lot like parole and kind of like probation – during he or she is subject to a series of reporting conditions and limitations imposed by the court. A U.S. Probation Officer supervises the former inmate, and holds the power to seek revocation of supervised release and return to prison under evidentiary and procedural standards that are rather lax, to say the least.

Fortunately for the former inmate, under 18 USC § 3583(e), someone on supervised release can get that supervision term ended early. The statute requires the court, in deciding whether to terminate early, to apply the 18 USC § 3553(a) sentencing factors. No surprise there, but many courts have been buying into the government’s argument that just being good while on supervision isn’t enough: the movant has to show something extraordinary or exceptional justifying saving the government money and the former inmate aggravation.

Aggravation? Well, yes. The former inmate must make monthly filings detailing his or her finances, purchases and employment. He or she cannot leave the federal district without permission of the Probation Officer. Often, he or she cannot change jobs without the Probation Officer’s OK, and woe betide anyone who has an unreported contact with someone who has a criminal record (that would be one out of three adult Americans). Oh, yes, the Probation Officer can search the former inmate’s home at any time without a warrant.

Aggravation? Well, yes. The former inmate must make monthly filings detailing his or her finances, purchases and employment. He or she cannot leave the federal district without permission of the Probation Officer. Often, he or she cannot change jobs without the Probation Officer’s OK, and woe betide anyone who has an unreported contact with someone who has a criminal record (that would be one out of three adult Americans). Oh, yes, the Probation Officer can search the former inmate’s home at any time without a warrant.

Nationally, the rate of violations that result in a hearing before the judge (where return to prison is a possibility) is about 17%. The prevalence of supervision violations, however, varies considerably among the federal judicial districts. In a July 2020 U.S. Sentencing Commission study, more than a third of individuals on supervision risked reimprisonment in violation hearings in the Southern District of California (42.1%), District of Minnesota (37.4%), Western District of Missouri (34.3%), District of Arizona (33.7%), and District of New Mexico (33.4%). In contrast, violations accounted for less than five percent of individuals on supervision in the Districts of Connecticut (4.5%) and Maryland (4.7%).

Nationally, the rate of violations that result in a hearing before the judge (where return to prison is a possibility) is about 17%. The prevalence of supervision violations, however, varies considerably among the federal judicial districts. In a July 2020 U.S. Sentencing Commission study, more than a third of individuals on supervision risked reimprisonment in violation hearings in the Southern District of California (42.1%), District of Minnesota (37.4%), Western District of Missouri (34.3%), District of Arizona (33.7%), and District of New Mexico (33.4%). In contrast, violations accounted for less than five percent of individuals on supervision in the Districts of Connecticut (4.5%) and Maryland (4.7%).

No wonder people on supervised release want to “get off paper,” as they put it. But few can meet the “extraordinary or exceptional reason” for early termination standard many courts impose.

Last week, the 3rd Circuit traced the twisted history of this “extraordinary or exceptional reason” requirement, and found no support for the standard.

The 3rd acknowledged that its prior non-precedential decisions had required “something exceptional or extraordinary” to warrant early termination, relying on the Second Circuit’s United States v. Lussier decision. “But this was a misreading of Lussier,” the 3rd Circuit said, in a rare acknowledgement that it had previously been wrong:

As the Second Circuit explained more recently, ‘Lussier does not require new or in order to modify conditions of release, but simply recognizes that changed circumstances may in some instances justify a modification’. In other words, extraordinary circumstances may be sufficient to justify early termination of a term of supervised release, but they are not necessary for such termination. We think that generally, early termination of supervised release under § 3583(e)(1) will be proper only when the sentencing judge is satisfied that new or unforeseen circumstances warrant it. That is because, if a sentence was ‘sufficient, but not greater than necessary’ when first pronounced, we would expect that something will have changed in the interim that would justify an early end to a term of supervised release. But we disavow any suggestion that new or unforeseen circumstances must be shown.”

Got that? “Extraordinary or exceptional reasons” no longer necessarily apply, except when they generally do.

Each person being supervised costs the government about $4,400.00, according to the Administrative Office of United States Courts. You’d think that saving that money might be a factor for more courts, especially where there is no discernible benefit to the supervisor or supervisee by continued oversight.

Each person being supervised costs the government about $4,400.00, according to the Administrative Office of United States Courts. You’d think that saving that money might be a factor for more courts, especially where there is no discernible benefit to the supervisor or supervisee by continued oversight.

But then, what’s $4,400 a year, even when multiplied by the 133,000 people under supervision? Answer: a half billion a year, a mere flyspeck to Uncle Sam.

United States v. Melvin, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 32683 (3rd Cir. October 16, 2020)

– Thomas L. Root